The Election of 1796

The election of 1796 was the first in which voters could choose between competing political parties. It was also the first test of whether the nation could transfer power through a contested election.

The Federalists chose Vice President, John Adams, as their presidential candidate, and the Republicans selected Thomas Jefferson. Both parties turned directly to the people for support, rallying supporters through the use of posters, handbills, and mass rallies. The Republicans condemned Adams as “the champion of rank, titles, and hereditary distinctions.” The Federalists claimed that Jefferson was intent on undermining religion and morality.

John Adams won the election, despite backstage maneuvering by Alexander Hamilton against him. Hamilton developed a complicated scheme to elect Thomas Pinckney of South Carolina, the Federalist candidate for Vice President. Under the electoral system at the time, each presidential elector was to vote twice, with the candidate who received the most votes becoming president and the candidate who came in second becoming Vice President. Hamilton convinced some Southern electors to drop Adams’s name from their ballots, while still voting for Pinckney. Thus Pinckney would receive more votes than Adams and be elected president. When New Englanders learned of this plan, they dropped Pinckney from their ballots, ensuring that Adams won the election. When the final votes were tallied, Adams received 71 votes, only three more than Jefferson. As a result, Jefferson became Vice President.

The Presidency of John Adams

The new president was a 61-year-old Harvard-educated lawyer who had been an early leader in the struggle for independence. Short, bald, overweight, and vain, he was known (behind his back) as “His Rotundity.”

Adams was the first president to live in what would later be called the White House. Just six of the structure’s thirty rooms were plastered. The White House’s main staircases were not installed for another four years. The mansion’s grounds were cluttered with workers’ shanties, privies, and stagnant pools of water. The president’s wife, Abigail, hung laundry to dry in the East Room. The city of Washington consisted of a brewery, a half-finished hotel, an abandoned canal, an empty warehouse and wharf, and 372 dwellings, “most of them small miserable huts.” Cows and hogs ran freely in the capital’s streets, and snakes frequented the city’s many bogs and marshes. The entire population consisted of 500 families and some 300 members of government.

During Adams’ presidency, the United States faced its most serious international crisis yet: an undeclared naval war with France. In the Jay Treaty, France perceived an American tilt toward Britain, especially in a provision permitting the British to seize French goods from American ships in exchange for financial compensation. France retaliated by capturing hundreds of vessels flying the United States flag.

Adams sent a negotiating team to France to settle the dispute. The French foreign minister continually postponed official negotiations. Meanwhile, three French emissaries (known later simply as X, Y, and Z) demanded that the Americans pay a bribe of $250,000 and provide a $10 million loan. The Americans refused to pay anything.

Word of the “XYZ affair” aroused a popular demand for war. The popular slogan was “millions for defense, but not one cent for tribute.” The Federalist-controlled Congress prepared for war by authorizing a 20,000-man army and calling George Washington out of retirement as commander in chief. During the winter of 1798, an undeclared naval war took place between France and the United States.

In the midst of the crisis, the Federalist-dominated Congress passed the notorious Alien and Sedition Acts, which were designed to suppress public criticism of the government. These laws:

- lengthened the period necessary before immigrants could become citizens from five to fourteen years

- gave the president the power to imprison or deport any foreigner believed to be dangerous to the United States

- made it a crime to attack the government with “false, scandalous, or malicious” statements or writings

to Thomas Jefferson’s election as president in 1800 and gave the Federalist party a reputation for political repression. Federalist prosecutors used the Sedition Act to convict ten editors, journalists, and printers. The most notorious use of the law to suppress dissent involved Luther Baldwin, who was arrested in a Newark, New Jersey tavern. While cannons roared to celebrate a presidential visit to the city, Baldwin was overheard saying “that he did not care if they fired through [the president’s] arse.” For his drunken remark, Baldwin was imprisoned for two months and fined.

Republicans accused the Federalists of violating fundamental liberties. The state legislatures of Kentucky and Virginia adopted resolutions written by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison denouncing the Alien and Sedition Acts as an infringement on freedom of expression. The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions advanced the idea that the states had a right to declare federal laws null and void, and helped to establish the theory of states’ rights.

Adams succeeded in averting full-scale war with France, but at the cost of a second term as President. Hamilton vowed to destroy Adams: “If we must have an enemy at the head of government, let it be one whom we can oppose, and for whom we are not responsible.”

The Revolution of 1800

In 1800, the nation again had a choice between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. Federalists feared that Jefferson would return power to the states, dismantle the army and navy, and overturn Hamilton’s financial system. The Republicans charged that the Federalists, by creating a large standing army, imposing heavy taxes, and using federal troops and the federal courts to suppress dissent, had shown contempt for the liberties of the American people. They worried that the Federalists’ ultimate goal was to centralize power in the national government and involve the United States in the European war on the side of Britain.

Jefferson’s Federalist opponents called him an “atheist in religion, and a fanatic in politics.” They claimed he was a drunkard and an enemy of religion. The Federalist Connecticut Courant warned that “there is scarcely a possibility that we shall escape a Civil War. Murder, robbery, rape, adultery, and incest will be openly taught and practiced.”

Jefferson’s supporters responded by charging that President Adams was a monarchist who longed to reunite Britain with its former colonies. Republicans even claimed that the president had sent General Thomas Pinckney to England to procure four mistresses, two for himself and two for Adams. Adams’s response: “I do declare if this be true, General Pinckney has kept them all for himself and cheated me out of my two.”

The election was extremely close. It was the Constitution’s Three-fifths clause, which counted three-fifths of the slave population in apportioning representation, that gave the Republicans a majority in the Electoral College. Jefferson appeared to have won by a margin of eight electoral votes. But a complication soon arose. Because each Republican elector had cast one ballot for Jefferson and one for Aaron Burr, Jefferson’s Vice Presidential running mate, the two men received exactly the same number of electoral votes.

Under the Constitution, the election was now thrown into the Federalist-controlled House of Representatives. Instead of emphatically declaring that he would not accept the presidency, Burr declined to say anything. So, the Federalists faced a choice. They could help elect the hated Jefferson—”a brandy-soaked defamer of churches”—or they could throw their support to the opportunistic Burr. Hamilton disliked Jefferson, but he believed he was a far more honorable man than Burr, whose “public principles have no other spring or aim than his own aggrandizement.”

As the stalemate persisted, Virginia and Pennsylvania mobilized their state militias. Recognizing, as Jefferson put it, “the certainty that a legislative usurpation would be resisted by arms,” the Federalists backed down. After six days of balloting and thirty-six ballots, the House of Representatives elected Thomas Jefferson the third president of the United States. And as a result of the election, Congress adopted the Twelfth Amendment to the Constitution, which gives each elector in the Electoral College one vote for President and one for Vice President.

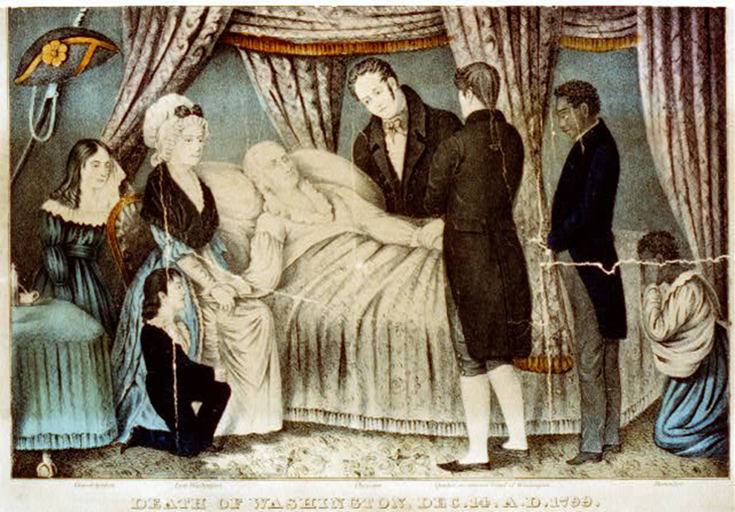

Death of Washington

Between two and three in the morning, December 13, 1799, George Washington woke his wife, complaining of severe pains. Martha Washington called for an overseer, who inserted a lancet in the former president’s arm and drew blood. Over the course of that day and the next, doctors arrived and attempted to ease General Washington’s pain by applying blisters, administering purges, and additional bloodletting, altogether removing perhaps four pints of Washington’s blood. Medical historians generally agree that Washington needed a tracheotomy (a surgical operation into the air passages), but this was too new a technique to be risked on the former president, who died on December 14.

During the early weeks of 1800, every city in the United States commemorated the death of the former leader. In Philadelphia, an empty coffin, a riderless horse, and a funeral cortege moved through the city streets. In Boston, business was suspended, cannons roared, bells pealed, and 6,000 people—a fifth of the city’s population—stood in the streets to express their last respects for the fallen general. In Washington, Richard Henry Lee delivered the most famous eulogy. He proclaimed that Washington was “First in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.”

In 1789, it was an open question whether the Constitution was a workable plan of government. For a decade, the nation faced bitter party conflict, threats of secession, and foreign interference with American shipping and commerce.

By any standard, the new nation’s achievements were impressive. During the first decade under the Constitution, the country adopted a bill of rights, protecting the rights of the individual against the power of the central and state governments; enacted a financial program that secured the government’s credit and stimulated the economy; and created the first political parties that directly involved the enfranchised segment of the population in national politics. In the face of intense partisan conflict, the United States became the first nation to peacefully transfer political power from one party to another as a result of an election. A nation, strong and viable, had emerged from its baptism by fire.