Years of Crisis

Hollywood Versus History

Why Alexander Hamilton Will Remain on the $10 Bill

The Treasury Department’s plan to remove Alexander Hamilton from the $10 bill was shelved thanks to a Broadway show.

Hamilton, who for decades was regarded as an elitist and a monarchist, became an unexpected sensation in a multi-ethnic hip-hop musical. The show is a period drama about the political intrigues of the early Republic, starring a cast of mostly black and Latino actors, with a score steeped in hip-hop.

The opening number poses a question:

How does a bastard

Orphan

Son of a whore and

A Scotsman

Dropped in

The middle of a forgotten

Spot in

The Caribbean by Providence

Impoverished

In squalor

Grow up to be a hero and a scholar?

Lin-Manuel Miranda performing this song:

How did a child born in the island backwater of the Caribbean island of Nevis become a storied founding father: an aide-de-camp of General George Washington, the prime mover in the creation of the United States financial system, the first secretary of the Treasury, the author of nearly half of the Federalist Papers, and the subject of America’s first political sex scandal?

When Alexander Hamilton was ten, his father abandoned him. When he was around twelve, his mother died of a fever in the bed next to his. He was adopted by a cousin, who promptly committed suicide. During those same years, his aunt, uncle and grandmother also died. A court in St. Croix seized all of his possessions, sold off his personal effects, and gave the rest to his mother’s first husband. By the time he was a young teenager, he and his brother were orphaned, alone, and destitute.

Within a decade he was effectively George Washington’s Chief of Staff, organizing the American revolutionary army and serving bravely in combat. Within two decades he was one of New York’s most successful lawyers and had written major portions of The Federalist Papers. Within three decades he had served as Treasury secretary and forged the modern financial and economic systems that are the basis for American might today. Within five decades he was dead at the hands of Aaron Burr.

His greatest achievements came as Treasury secretary. He was confronted by an economically weak and fractious nation. He nationalized the debt, binding the states together, and created the fluid capital markets that are today the engine of world capitalism. He was working at a time when many around him had an entirely static view of economics. They scorned credit, banks, and stock markets, and considered manufacturing the least productive form of economic activity.

When he was Treasury secretary in the 1790s, there were only five securities traded. Three were Treasury securities created by Hamilton. The fourth were shares of the Bank of the United States, created by Hamilton. The fifth, shares of the Bank of New York—the first private bank of New York—were also created by Hamilton. So he literally had created the entire infrastructure of Wall Street.

When he became Treasury secretary, the country was bankrupt; American debt was selling for ten or fifteen cents on the dollar. By the time he left office five years later, the country’s credit was as good as anyone else’s in the world. Most revolutionary regimes—and that’s what ours was—would simply have repudiated the debt. But Hamilton felt it was important to honor it. He provided the country with an economic and financial maturity that enabled it to give the Constitution and federal government a fair test.

Hamilton versus Jefferson

It’s the political equivalent to Batman versus Superman.

American political history is an ongoing struggle between Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton.

Hamilton was a modernizer. He favored bigness. He wanted to make the United States an economic and military power as great as any in Europe. To that end, he favored a strong central government and the growth of finance, trade, and industry.

Jefferson, in contrast, was suspicious of centralized power. He was hostile toward industry, cities, and banks and opposed a powerful standing army and navy. He was a slaveholder who believed in states’ rights, a weak central government, cutting taxes, strict construction of the Constitution and legislative power.

Their conflict is a constant in American history and it has taken on new life in our own time.

Hamilton dreamed of a vibrant economy that would allow aspiring meritocrats like himself to rise and realize their full capacities. He sought to smash the aristocratic fiefs enjoyed by Southern landowners like Jefferson and to replace them with a diversified marketplace that would be open to immigrants and the lowborn.

A self-made man and a staunch believer in meritocracy, Hamilton wanted an energetic government that would open doors to opportunity seekers like himself. He opposed states’ rights, favored an activist central government, a very liberal interpretation of the Constitution, and executive rather than legislative powers.

Hamilton’s life is filled with paradoxes. The biggest involves slavery. Born amid Caribbean slavery, he later married into a slaveholding family. Yet he also founded one of the first two anti-slavery societies in the world, and helped to found New York City’s African Free Schools, which educated many of the nation’s leading black abolitionists.

This fight between Jefferson and Hamilton was about what sort of country America should be, and what sort of people should govern. Hamilton embraced the urban, enterprising virtues: vigor, drive, competition. Jefferson dreamed of a country that would be pastoral, egalitarian and decentralized. Hamilton won the battle, but not the affections of posterity.

French Revolution

In the struggle which was necessary, many guilty persons fell without the forms of trial, and with them some innocent. These I deplore as much as any body, & shall deplore some of them to the day of my death. But I deplore them as I should have done had they fallen in battle. It was necessary to use the arm of the people, a machine not quite so blind as balls and bombs, but blind to a certain degree. A few of their cordial friends met at their hands the fate of enemies. But time and truth will rescue & embalm their memories, while their prosperity will be enjoying that very liberty for which they would never have hesitated to offer up their lives. The liberty of the whole earth was depending on the issue of the contest, and was ever such a prize won with so little innocent blood? My own affections have been deeply wounded by some of the martyrs to this cause, but rather than it should have failed, I would have seen half the earth desolated. Were there but an Adam & an Eve left in every country, & left free, it would be better than as it now is.

| Jefferson | Hamilton |

| View of the people “Men…are naturally divided into two parties. Those who fear and distrust the people…Those who identify themselves with the people, have confidence in them, cherish and consider them as the most honest and safe…depository of the public interest.” “…there is a natural aristocracy among men. The grounds of this are virtue and talents.” | “All communities divide themselves into the few and the many. The first are the rich and well born; the other, the mass of people… The people are turbulent and changing; they seldom judge or determine right. Give therefore to the first class a…permanent share in the government…they therefore will ever maintain good government.” |

| View of government “I am not a friend to a very energetic government. It is always oppressive. It places the governors indeed more at their ease, at the expense of the people.” | “I believe the British government forms the best model the world ever produced, and such has been its progress in the minds of the many, that this truth gradually gains ground. This government has for its object public strength and individual security.” |

| View of debt “…No man is more ardently intent to see the public debt soon and sacredly paid off then I am. This exactly marks the difference between Colonel Hamilton’s views and mine, that I would wish the debt paid tomorrow; he wishes it never to be paid, but always to be a thing w | “A national debt, if not excessive, will be to us a national blessing.” |

| Construing the Constitution “I consider the foundation of the Constitution as laid on this ground: That ‘all powers not delegated to the United States, by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States or to the people.’ To take a single step beyond the boundaries thus specially drawn around the powers of Congress, is to take possession of a boundless field of power, no longer susceptible of any definition.” | “The powers contained in a constitution…ought to be construed liberally in advancement of the public good.” |

| griculture versus industry “Those who labour in the earth are the chosen people of God, if ever he had a chosen people, whose breasts he has made his peculiar deposit for substantial and genuine virtue….Corruption of morals in the mass of cultivators is a phenomenon of which no age nor nation has furnished an example…. Generally speaking the proportion which the aggregate of the other classes of citizens bears in any state to that of its husbandmen, is the proportion of its unsound to its healthy parts….The mobs of great cities add just so much to the support of pure government, as sores do to the strength of the human body.” | “…manufacturing establishments not only occasion a positive augmentation of the Produce and Revenue of the Society, but that they contribute essentially to rendering them greater than they could possibly be, without such establishments. These circumstances are: 1. The division of labour. 2. An extension of the use of Machinery. 3. Additional employment to classes of the community not ordinarily engaged in the business. 4. The promoting of emigration from foreign Countries. 5. The furnishing greater scope for the diversity of talents and dispositions which discriminate men from each other. 6. The affording a more ample and various field for enterprise. 7. The creating in some instances a new, and securing in all, a more certain and steady demand for the surplus produce of the soil. |

| French Revolution In the struggle which was necessary, many guilty persons fell without the forms of trial, and with them some innocent. These I deplore as much as any body, & shall deplore some of them to the day of my death. But I deplore them as I should have done had they fallen in battle. It was necessary to use the arm of the people, a machine not quite so blind as balls and bombs, but blind to a certain degree. A few of their cordial friends met at their hands the fate of enemies. But time and truth will rescue & embalm their memories, while their prosperity will be enjoying that very liberty for which they would never have hesitated to offer up their lives. The liberty of the whole earth was depending on the issue of the contest, and was ever such a prize won with so little innocent blood? My own affections have been deeply wounded by some of the martyrs to this cause, but rather than it should have failed, I would have seen half the earth desolated. Were there but an Adam & an Eve left in every country, & left free, it would be better than as it now is. | “Would to heaven that we could discern in the mirror of French affairs the same humanity, the same decorum, the same gravity, the same order, the same dignity, the same solemnity, which distinguished the cause of the American Revolution. Clouds and darkness would not then rest upon the issue as they now do. I own I do not like the comparison.” |

Years of Crisis

In 1793 and 1794 a series of crises threatened to destroy the new national government.

- France tried to entangle America in its war with England;

- Armed rebellion erupted in western Pennsylvania;

- Indians in Ohio threatened American expansion; and

- War with Britain appeared imminent.

In April 1793, a French minister, Edmond Charles Genet, arrived in the United States and tried to persuade American citizens to join in revolutionary France’s “war of all peoples against all kings.” Genet passed out letters authorizing Americans to attack British commercial vessels. Washington regarded these activities as clear violations of U.S. neutrality, and demanded that France recall its hot-headed minister. Fearful that he would be executed if he returned to France, Genet requested and was granted political asylum.

The Genet affair intensified party divisions. From Vermont to South Carolina, supporters of the French Revolution organized Democratic-Republican clubs. Hamilton suspected that these societies really existed to stir up grassroots opposition to the Washington administration.

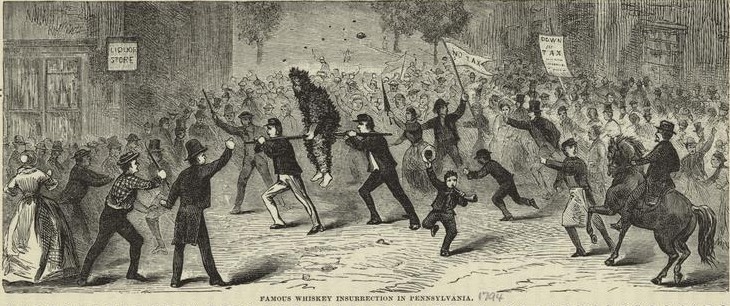

Political polarization was further intensified by the outbreak of popular protests in western Pennsylvania against Hamilton’s financial program. To help pay off the nation’s debt, Congress passed a tax on whiskey. On the frontier, the only practical way to transport and sell surplus corn was to distill it into whiskey. Frontier farmers regarded a tax on whiskey in the same way as American colonists had regarded Britain’s stamp tax.

By 1794, western Pennsylvanians had had enough. Some 7,000 frontiersmen marched on Pittsburgh to stop collection of the tax. Determined to set a precedent for the federal government’s authority, Washington gathered an army of 15,000 militiamen to disperse the rebels. In the face of this overwhelming force, the uprising collapsed. The new government had proved that it would enforce laws enacted by Congress.

Thomas Jefferson took a very different view of the “Whiskey Rebellion.” He believed that the government had used the army to stifle legitimate opposition to unfair government policies.

Expansion into the Ohio country provoked another crisis.

The end of the American Revolution unleashed a rush of white settlers into frontier Georgia, Kentucky, Tennessee, Ohio, and western New York. Hundreds died as Indians resisted the influx of whites onto their lands. To open the Ohio country to white settlement, President Washington dispatched three armies. Twice, a confederacy of eight tribes led by Little Turtle, chief of the Miamis, defeated American forces. But in 1794, a third army defeated the Indian alliance at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in northwestern Ohio. Under the Treaty of Greenville (1795), Native Americans ceded much of the present state of Ohio in return for cash and a promise that the federal government would treat the Indian nations fairly in land dealings.

The year 1794 brought a crisis in America’s relations with Britain. For a decade, Britain had refused to evacuate forts in the Northwest Territory. Control of those forts allowed the British to monopolize the fur trade. Frontier settlers believed that British officials sold firearms to the Indians and incited uprisings against white settlers. War appeared imminent when British warships stopped 300 American ships carrying food supplies to France and to France’s overseas possessions and forced sailors suspected of deserting from British ships into the British navy.

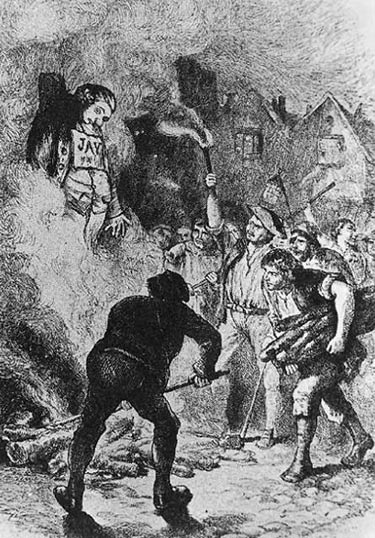

To end the crisis, President Washington sent Chief Justice John Jay to London to negotiate a settlement with the British. Britain agreed to evacuate its forts on American soil and to cease harassing American shipping (provided the ships did not carry supplies to Britain’s enemies). Britain also agreed to pay damages for the ships it had seized and to permit the United States to trade with India and carry on restricted trade with the British West Indies. But Jay failed to win compensation for slaves carried off by the British Army during the Revolution.

The Jeffersonians denounced the treaty as a give-away to Northern shipping interests. Southern slaveowners were especially angry because they received no compensation for the slaves who had fled to the British during the Revolution. In Boston, graffiti appeared on a wall: “Damn John Jay! Damn everyone who won’t damn John Jay!! Damn everyone that won’t put lights in his windows and sit up all night damning John Jay!!!”

President Washington, however, was now in a position to retire gracefully. He had pushed the British out of the western forts, opened the Ohio country to white settlement, and avoided war with Britain. In a Farewell Address, published in a Philadelphia newspaper in 1796, Washington warned his countrymen against the growth of partisan divisions. He also called on the country to avoid “permanent alliance with any portion of the foreign world.” It would not be until after World War II that the country would establish peacetime alliances with foreign nations.