Challenges Facing the Nation

Challenges Facing the Nation

During the 1790s, the young republic faced many of the same problems that confronted the newly independent nations of Africa and Asia in the twentieth century. Like other nations born in anti-colonial revolutions, the United States faced the challenge of building a sound economy, preserving national independence, and creating a stable political system which provided a legitimate place for opposition.

In 1790, it was not at all obvious that the Union would long survive. George Washington thought that the new government would not last twenty years. One challenge was to consolidate public support. Only about five percent of adult white males had voted to ratify the new Constitution and two states, North Carolina and Rhode Island, continued to support the Articles of Confederation. Vermont threatened to join Canada.

The new nation also faced economic and foreign policy problems.

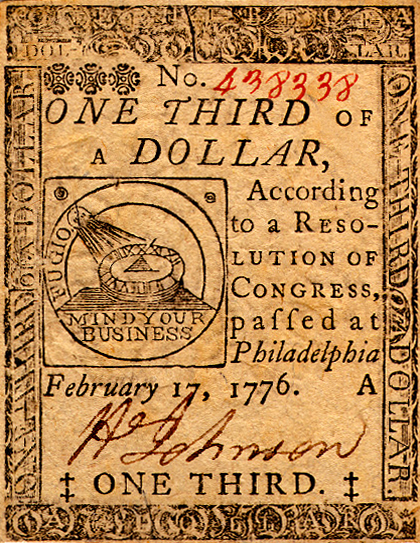

- A huge debt remained from the Revolutionary War and paper money issued during the conflict was virtually worthless.

- In violation of the peace treaty of 1783 ending the Revolutionary War, Britain continued to occupy forts in the Old Northwest.

- Spain refused to recognize the new nation’s southern and western boundaries.

Establishing the Machinery of Government

The U.S. Constitution created a general framework of government. It would be up to the first president and first Congress to fill in the details.

The new government consisted of nothing more than seventy-five post offices, a large debt, a small number of unpaid clerks, and an army of just forty-six officers and 672 soldiers. There was no federal court system, no navy, and no system for collecting taxes.

The Senate devoted three weeks to debating how the president should be addressed. One committee proposed “His Highness the President of the United States and Protector of the Rights of the Same.”

The House of Representatives, under the leadership of James Madison, considered more pressing problems.

- To raise revenue, it passed a tariff on imports and a tax on liquor.

- To encourage American shipping, it imposed duties on foreign vessels.

- To provide a structure for the executive branch of the government, it created departments of State, Treasury, and War.

The Judiciary Act of 1789 organized a federal court system, which consisted of a Supreme Court with six justices, a district court in each state, and three appeals courts.

To strengthen popular support for the new government, Congress also approved a Bill of Rights. These first ten amendments guaranteed the rights of free press, free speech, and religion; the right to peaceful assembly; and the right to petition government. The Bill of Rights also ensured that the national government could not infringe on the right to trial by jury. In an effort to reassure Anti-Federalists that the powers of the new government were limited, the tenth amendment “reserved to the States respectively, or to the people” all powers not specified in the Constitution.

Defining the Presidency

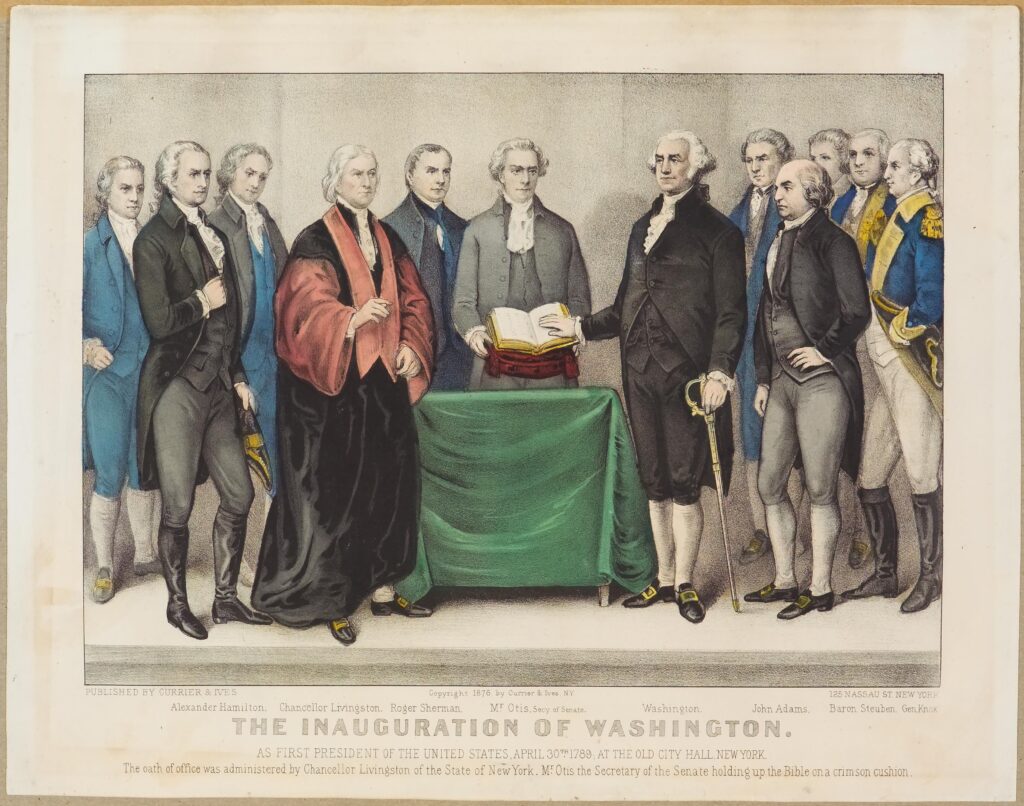

The Constitution provided only a broad outline of the office and powers of the president. It would be up to George Washington, as the first president, to define the office.

It was unclear, for example, whether the president was to personally run the executive branch or, instead, to serve as a constitutional monarch and to delegate responsibility to the vice president and executive officers (the cabinet).

Washington favored a strong and active role for the president. Modeling the executive branch along the lines of a general’s staff, Washington consulted his cabinet officers and listened to them carefully, but he made the final decisions, just as he had done as Commander-in-Chief.

The relationship between the executive and legislative branches was also uncertain. Should a president, like Britain’s prime minister, personally appear before Congress to defend administration policies? Should the Senate have sole power to dismiss executive officers?

The answers to such questions were not clear. Washington insisted that the president could dismiss presidential appointees without the Senate’s permission. A bitterly divided Senate approved this principle by a single vote.

With regard to foreign policy, Washington tried to follow the literal words of the Constitution, which stated that the president should negotiate treaties with the advice and consent of the Senate. He appeared before the Senate in person to discuss a pending Indian treaty. The senators, however, refused to provide immediate answers and referred the matter to a committee. “This defeats every purpose of my coming here,” Washington declared. In the future he negotiated treaties first and then sent them to the Senate for ratification.

Alexander Hamilton’s Financial Program

The most pressing problems facing the new government were economic. As a result of the revolution, the federal government had acquired a huge debt: $54 million including interest. The states owed another $25 million. Paper money issued under the Continental Congresses and Articles of Confederation was worthless. Foreign credit was unavailable.

The person assigned to the task of resolving these problems was 32-year-old Alexander Hamilton. Born out of wedlock in the West Indies in 1757, he was sent to New York at the age of fifteen for schooling. One of New York’s most influential attorneys, he played a leading role in the Constitutional Convention and wrote 51 of the 85 Federalist Papers, urging support for the new Constitution. As Treasury Secretary, Hamilton designed a financial system that made the United States the best credit risk in the western world.

The paramount problem facing Hamilton was a huge national debt. He proposed that the government assume the entire debt of the federal government and the states. His plan was to retire the old depreciated obligations by borrowing new money at a lower interest rate.

States like Maryland, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and Virginia, which had already paid off their debts, saw no reason why they should be taxed by the federal government to pay off the debts of other states like Massachusetts and South Carolina. Hamilton’s critics claimed that his scheme would provide enormous profits to speculators who had bought bonds from Revolutionary War veterans for as little as ten or fifteen cents on the dollar.

For six months, a bitter debate raged in Congress, until James Madison and Thomas Jefferson engineered a compromise. In exchange for Southern votes, Hamilton promised to support locating the national capital on the banks of the Potomac River, the border between two Southern states, Virginia and Maryland.

Hamilton’s debt program was a remarkable success. By demonstrating Americans’ willingness to repay their debts, he made the United States attractive to foreign investors. European investment capital poured into the new nation in large amounts.

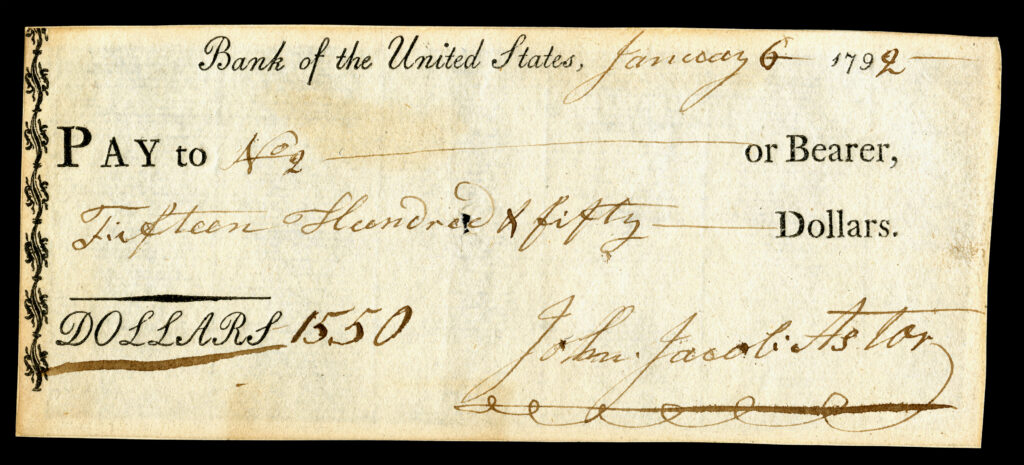

Hamilton’s next objective was to create a Bank of the United States, modeled after the Bank of England. A national bank would collect taxes, hold government funds, and make loans to the government and borrowers. One criticism directed against the bank was that it was “unrepublican”—it would encourage speculation and corruption. The bank was also opposed on constitutional grounds. Adopting a position known as “strict constructionism,” Thomas Jefferson and James Madison charged that a national bank was unconstitutional since the Constitution did not specifically give Congress the power to create a bank.

Hamilton responded to the charge that a bank was unconstitutional by formulating the doctrine of “implied powers.” He argued that Congress had the power to create a bank because the Constitution granted the federal government authority to do anything “necessary and proper” to carry out its constitutional functions (in this case its fiscal duties).

In 1791, Congress passed a bill creating a national bank for a term of twenty years, leaving the question of the bank’s constitutionality up to President Washington. The president reluctantly decided to sign the measure out of a conviction that a bank was necessary for the nation’s financial well-being.

Finally, Hamilton proposed to aid the nation’s infant industries. Through high tariffs designed to protect American industry from foreign competition, government subsidies, and government-financed transportation improvements, he hoped to break Britain’s manufacturing hold on America.

The most eloquent opposition to Hamilton’s proposals came from Thomas Jefferson, who believed that manufacturing threatened the values of an agrarian way of life. Hamilton’s vision of America’s future challenged Jefferson’s ideal of a nation of farmers, tilling the fields, communing with nature, and maintaining personal freedom by virtue of land ownership.

Alexander Hamilton offered a remarkably modern economic vision based on investment, industry, and expanded commerce. Most strikingly, it was an economic vision that had no place for slavery. Before the 1790s, the American economy—North and South—was intimately tied to a trans-Atlantic system of slavery. States south of Pennsylvania depended on slave labor to produce tobacco, rice, indigo, and cotton. The Northern states conducted their most profitable trade with the slave colonies of the West Indies. A member of New York’s first antislavery society, Hamilton wanted to reorient the American economy away from slavery and colonial trade.

Although Hamilton’s economic vision more closely anticipated America’s future, by 1800 Jefferson and his vision had triumphed. Jefferson’s success resulted from many factors, but one of the most important was his ability to paint Hamilton as an elitist defender of deferential social order and an admirer of monarchical Britain, while picturing himself as an ardent proponent of republicanism, equality, and economic opportunity. Unlike Jefferson, Hamilton doubted the capacity of common people to govern themselves.

Jefferson’s vision of an egalitarian republic of small producers—of farmers, craftsmen, and small manufacturers—had powerful appeal for subsistence farmers and urban artisans fearful of factories and foreign competition. In increasing numbers, these voters began to join a new political party led by Jefferson.

Birth of Political Parties

The framers of the Constitution had not prepared their plan of government with political parties in mind. They hoped that the “better sort of citizens” would debate key issues and reach a harmonious consensus regarding how best to legislate for the nation’s future. Thomas Jefferson reflected widespread sentiments when he declared in 1789, “If I could not go to heaven but with a party, I would not go there at all.”

Yet despite a belief that parties were evil and posed a threat to enlightened government, the nation’s first political parties emerged in the mid-1790s. Several factors contributed to the birth of parties.

The Federalists, under the leadership of George Washington, John Adams, and Alexander Hamilton, feared that their opponents wanted to destroy the Union, subvert morality and property rights, and ally the United States with revolutionary France.

The Republicans, under the leadership of Thomas Jefferson, feared that the Federalists were trying to establish a corrupt monarchical society, like the one that existed in Britain, with a standing army, high taxes, and government-subsidized monopolies.