The Formative Decade

The Formative Decade

Politically and economically, the 1790s were the nation’s formative decade. During this decade, the United States implemented the new Constitution, adopted a bill of rights, created its first political parties, and built a new national capital city in Washington, D.C. The 1790s were also years of rapid economic and demographic growth. It was during this critical decade that the United States established the foundations of a prosperous, growing economy.

But the 1790s were also years of conflict and threats of civil war. At the root of conflict were two divergent visions of the kind of nation the United States should become.

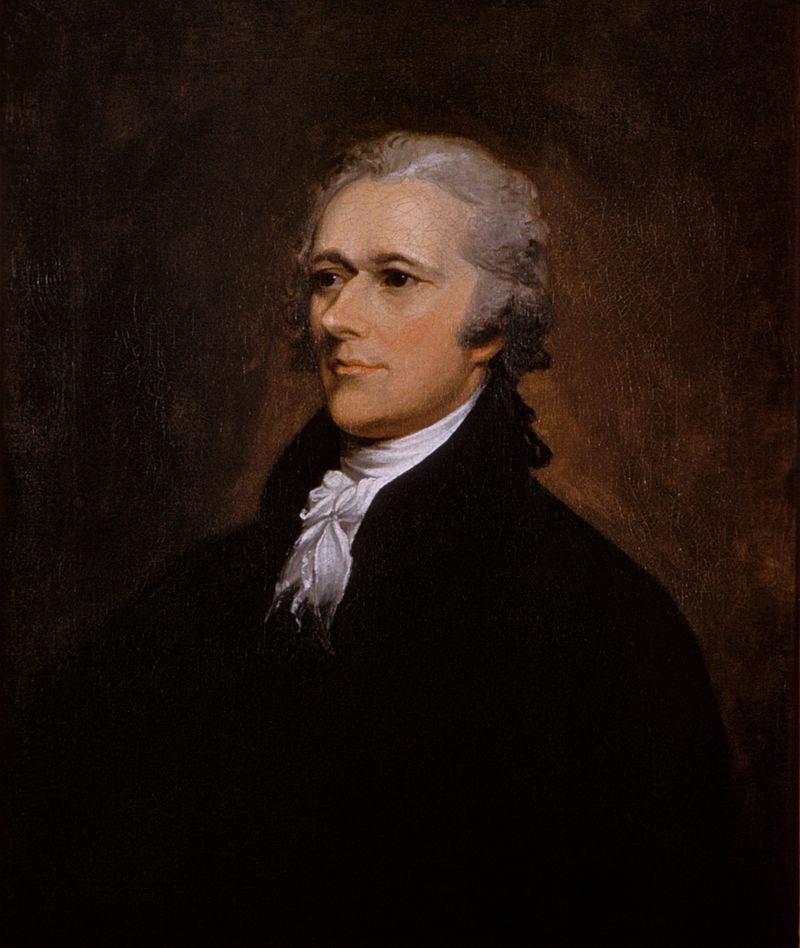

Rarely in American history has political rhetoric been so impassioned. At the end of the decade, the Federalists warned that if Jefferson were elected president, Americans would “see your dwellings in flames” and “female chastity violated.” The Hamiltonians and the Jeffersonians both feared for the future of the new nation. Hamilton and his supporters were convinced that the Jeffersonians sought to subvert legitimate government, private property, religion, and morality, and ally the United States with revolutionary France.

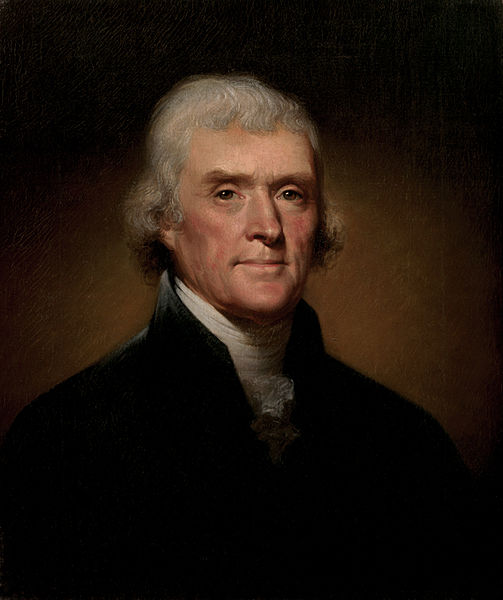

The Jeffersonians believed that Hamilton and his supporters wanted to recreate the monarchical society that Americans had rebelled against in 1776 and that they were willing to use the army to suppress the peoples’ liberties. Alexander Hamilton envisioned an economic and military power modeled on Britain, with a strong central government, a national bank, a standing army, and flourishing industry. Thomas Jefferson offered a very different ideal. He envisioned an agrarian society, without a central bank, taxes, a standing army, or a large government bureaucracy.

What Was the United States Like in 1790?

The population was quite small—only about a quarter the size of England’s and just a sixth the size of France’s. Just 3,929,214 people lived in the country, about half in the Northern states, half in the South.

The population was also overwhelmingly rural. In a population of nearly 4 million, only two cities had more than 25,000 residents and just 202,000 people lived in the 24 towns or cities with at least 2,500 inhabitants.

In 1790, the population remained clustered along the Atlantic coast. The population center was located on Maryland’s eastern shore, a few miles from the ocean.

By European standards, the American population was exceptionally diverse. A fifth of the entire population was African-American. Among whites, three-fifths were English in ancestry and another fifth was Scottish or Irish. The remainder was of German, Dutch, French, Swedish, or other background. The population was also extraordinarily youthful, with half of the people under the age of sixteen.

The economy was still quite undeveloped. There were fewer than one hundred newspapers in the entire country; three banks (with total capital of less than $5 million); and three insurance companies. And yet, the United States was perched on the edge of an extraordinary decade of growth.

During the 1790s, the American population grew very rapidly, climbing over twenty percent to more than five million in 1800. Population growth was particularly rapid in cities and in the West. The population of Kentucky and Tennessee grew nearly 300 percent in the 1790s, and by 1800, Kentucky had more people than five of the original thirteen states.

American society also made tremendous economic advances. During the 1790s, states chartered almost ten times more corporations, banks, and transportation companies than during the 1780s. Cotton production rose from 3,000 bales to 73,000. The growth of foreign trade was particularly rapid, climbing from just $19 million in 1790 to $85 million in 1800. The number of patents issued rose from just three in 1790 to 44 in 1800.

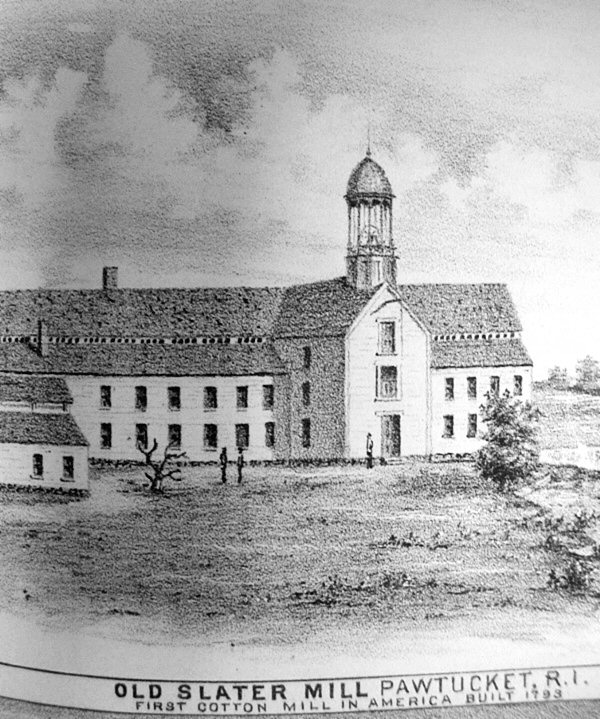

In 1791, an English immigrant named Samuel Slater introduced the factory system into the United States in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. Other factories erected in the 1790s produced iron, brass, paper, glass, firearms, nails, umbrellas, and hats. In 1790, a Connecticut Yankee named John Fitch started the first commercial steamship service connecting Philadelphia with Trenton, New Jersey.

In 1800, as in 1790, the United States remained a nation of farms, plantations, and small towns, of yeoman, slaves, and artisans. Nevertheless, the nation was undergoing far-reaching social and economic transformations. During the 1790s, the number of newspapers doubled. Between 1783 and 1800, Americans founded seventeen new colleges and a large number of female academies. During the 1790s, 266 circulating libraries opened; New Hampshire and Kentucky founded new medical schools; and literary, historical, and philosophic societies, like the Massachusetts Historical Society organized in 1791, multiplied.

The transformations in the economy had far-reaching social implications. Older hierarchies and bonds of dependency broke down. Indentured servitude began to disappear. Servants became “help.” Wealth became more unequally distributed. For the first time in American history, labor unions emerged. The gap between rich and poor widened.

Sight and Sound

Art in Early America

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Europeans treated American culture with contempt. They charged that America was too commercial and materialistic, too preoccupied with money and technology to produce great art and literature. “In the four quarters of the globe,” asked one English critic, “who reads an American book? or goes to an American play? or looks at an American picture or statue?”

Writing toward the end of the nineteenth century, the novelist Henry James explained that the United States, in its founding decades, had none of the things necessary for great art: “No sovereign, no court, no personal loyalty, no aristocracy, no church, no clergy, no army, no diplomatic service, no country gentlemen, no palaces, no castles, nor manors, nor old country houses, nor parsonages, nor thatched cottages nor ivied ruins; no cathedrals, nor abbeys, nor little Norman churches; no great Universities nor public schools—no Oxford, nor Eton, nor Harrow; no literature, no novels, no museums, no pictures, no political society, no sporting class—no Epsom nor Ascot!”

During the eighteenth century, basic artistic implements, such as paints, brushes, and canvases, were unavailable. Most painters were simply skilled craftspeople who devoted most of their time to painting houses, furniture, or signs. They were untrained and lacked the self-consciousness that we associate with real artists. They were imitators and illustrators, not artists.

Not surprisingly, the country’s few talented portrait painters of the late eighteenth century—John Singleton Copley, Charles Willson Peale, and Gilbert Stuart—spent much of their lives abroad.

There were three major obstacles to the creation of great art in America. The first was a lack of wealthy patrons. In the colonies, there were no churches or colonial assemblies eager to commission art works to embellish their buildings or adorn their rituals. There was no powerful monarchy that wanted art to glorify the state, and there was no aristocracy that wanted to beautify its estates.

A second problem was a problem of democracy. In a commercial society, few people were willing to pay for fine art. The mass of Americans preferred popular culture.

The third problem was a problem of legitimacy. Colonial Americans were deeply uneasy about visual images. The Puritan ancestors had a taboo about graven images, icons, and mirrors. Before the end of the eighteenth century, there were very few paintings, drawings, or visual images in colonial America. Protestant America was a culture of words, not of images.

Many members of the Revolutionary generation regarded art with disdain. Art was viewed as effete, aristocratic, and European. Even in the nineteenth century, Americans still had Puritan-like anxieties about indulging the senses. Americans associated the visual arts with luxury, corruption, and sensual appetite. Declared one early President: “When a people get a taste for the fine arts, they are ruined.”

In addition, America was a country filled with middle-class taboos, which limited the kinds of subjects that artists could treat. Artists could not include nudity in their paintings. There would be an ongoing reluctance to deal with the city and with the human body.

The United States would gradually overcome these obstacles and develop a distinctive artistic tradition. In its formative era, the United States faced a problem that we now call “post-colonialism.” Americans felt a profound sense of cultural inferiority; they were very vulnerable to the charge that they were vulgar, materialistic, and lacked visual acuity. There was a great fear that art in America would be derivative of art in Europe.

Some Americans wanted the United States to create a “democratic” art that would be different and distinct from art in Europe and would help the United States establish an independent national identity.

During the nineteenth century, there was a widespread consensus that art needed to serve non-artistic functions: it needed to be educational or moral, to uplift the senses, and to shape character. Artists adopted several strategies to legitimate art.

One strategy was to mimic the art of classical Greece and Rome. Classical art had republican associations. Classical art emphasized simplicity, purity, balance—ideals that were stressed by Americans of the Revolutionary era who were heavily influenced by the Enlightenment.

A second strategy was to create historical paintings. The American public hungered for visual representations of the great events of the American Revolution, and works such as John Trumbull’s Revolutionary War battle scenes and his painting of the Declaration of Independence (1818) fed the public’s appetite.

A third strategy involved romantic landscape paintings. Landscapes attracted an enormous popular audience. Portrayals of the American landscape by artists of the Hudson River school, such as Thomas Cole, Albert Bierstadt, and Frederick Church, evoked a sense of the immensity, power, and grandeur of nature, which had not yet been tamed by an expansive American civilization. Landscapes also offered a way for Americans to commune with the divine. Furthermore, landscape paintings represented a reaction against the urban and industrial growth of cities that threatened to destroy the beauty of the American environment.

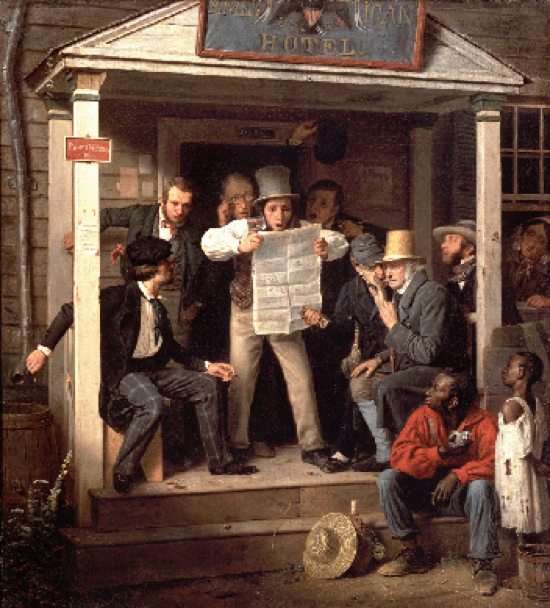

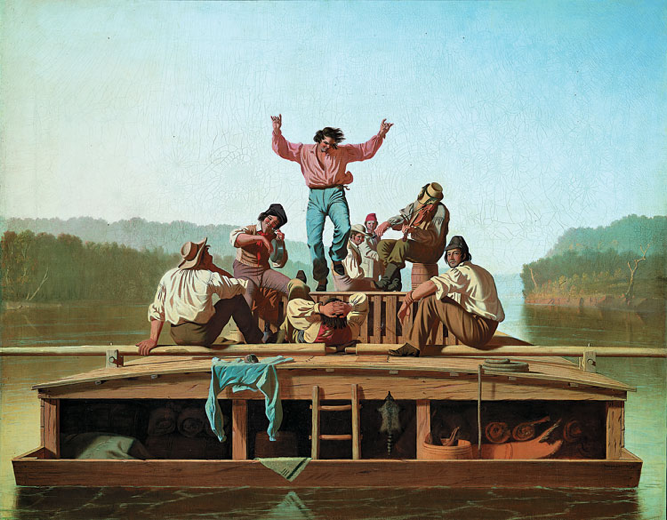

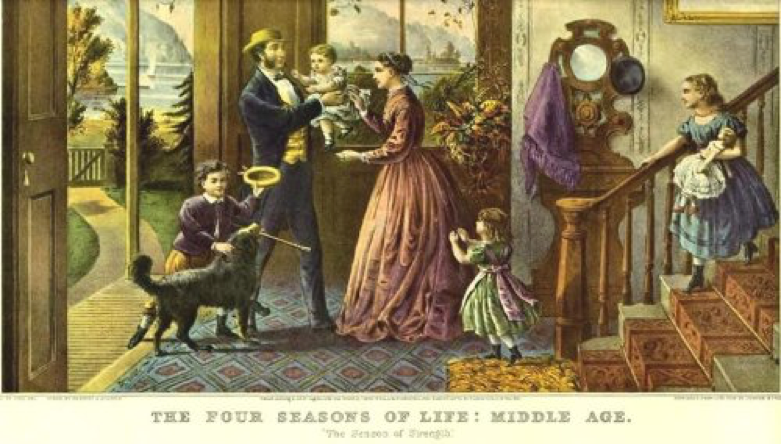

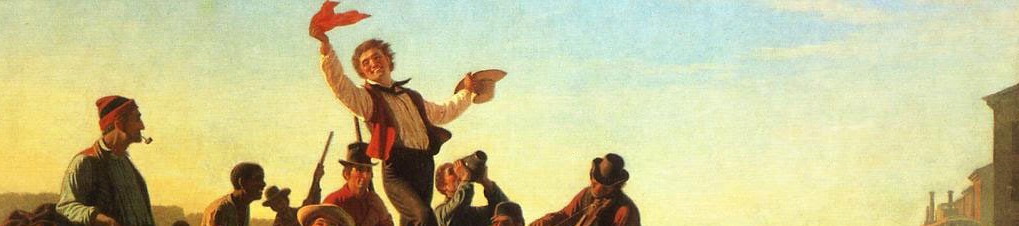

But the most important strategy involved the production of narrative and genre paintings, which depict scenes of everyday life.