Creating a National Music

Sight and Sound

Creating a National Music

Music pervades our lives. Surround sound is not just a technology. It is a social reality. We live in a world of music. Various kinds of music serve as a backdrop of our lives. We hear music on car radios, cellphones, and music videos. We also expect our television shows and movies to be accompanied by music.

It is no accident that one of the most bitter legal battles of our time—over Napster and other kinds of computer software–involves downloading of music.

Yet formal music training and music education have declined sharply in recent years. While many students continue to play in school bands and orchestras, regular courses in music have reduced in order to cut costs. The result is that while young people probably listen to more music than ever before, there is no reason to think that most young people know much about music itself: about reading music, music theory, or the history of music.

The Global Influence of American Music

Just as Hollywood has left its mark on movie-making around the world, American popular music dominates the world’s tastes in popular music. This has been true since the time of Stephen Foster before the Civil War.

Partly this reflects the power to absorb foreign music, much as Hollywood has attracted foreign actors and directors. Ricky Martin, Shakira, and Enrique Iglesias are only a few of the most recent examples.

Partly it reflects American dominance of global media. American music videos are broadcast across the entire world.

But it also reflects the genuine appeal of American music. Its novelty, but also its mixture of sentimental, the rebellious, the flippant, and the humorous.

From the early nineteenth century, composers have viewed popular music as a democratic art form: a music for the people. It was meant to be entertaining. It was meant to address problems of the human condition, especially love.

The Soundtrack of Their Lives

Music looms particularly loudly in the lives of adolescents. Teens watch less television than any other group in society—but they listen to much more music. The young use music to pass time, to relax, to create a mood of excitement.

Between grades seven and twelve, adolescents spend over 10,000 hours listening to music, as much time as they spend in school.

On average, American youth listen to music and watch music videos four to five hours a day, which is more time than they spend with their friends outside of school or watching television.

Music alters and intensifies their moods, furnishes much of their slang, dominates their conversations and provides the ambiance at their social gatherings. Music styles define the crowds and cliques they run in. Music personalities provide models for how they act and dress.

They use music most to control mood and enhance emotional states. “Music can make a good mood better and allow us to escape or ‘work through’ a bad one. But it can also be used to enhance bad moods.

Adolescents also use music to gain information about the adult world, to withdraw from social contact (such as using a Ipod and large headphones as a barrier, not unlike an adult hiding behind a newspaper at the breakfast table), to facilitate friendships and social settings, or to help them create a personal identity.

Adolescents actively use music to satisfy particular social, emotional, and developmental needs. In our society, young people face a variety of pressing psychological issues involving sexuality, identity formation, dependency, and separation from parents, and music provides a vehicle for dealing with these problems. It provides a distraction from boredom and parental nagging; it assures the young that they are not alone.

Young people use music to resist authority at all levels, assert their personalities, develop peer relationships and romantic entanglements, and learn about things that their parents and the schools aren’t telling them.

Choice of music is especially important in helping young people assert an independent identity. Taste in music helps determine your friends and your social group. Particular kinds of music reflect distinct sensibilities and values. It means something different to like rap than to like salsa.

Kinds of Music

Beginning in the 1970s, the types of music increased sharply. Such sounds as heavy metal, hard rock, classic rock, rasta, teeny bop, soul, reggae, hi-energy (gay disco), grunge, hip-hop, African, hybrid, Salsa, and Tejano reflected the “tribalization” of youth—the fracturing of youth into a wide range of distinct segments.

Choice of music is a personal and cultural statement. It is a way to express individuality and unconventionality.

Different kinds of music have different associations. Heavy metal is associated with rebelliousness, emotional intensity, anger, and hypermasculinity,

Music has also taken diverse forms. There is secular music and sacred and devotional music. There is classical music and popular music. There is popular music, concert music. There is country and western music, rhythm and blues, and pop.

Gender and Music

No where is the adolescent gender gap greater than in musical tastes. Young men tend to prefer hard rock, hip hop, and heavy metal; they tend to think of soft music as unhip and uncool. Young women tend to prefer dance music.

Young men’s music tends to be louder and to feature a pulsating beat and discordant sounds, while young women’s music tends to be softer and more sentimental.

Distinct musical genres tend to appeal to adolescent males and females. Rock and rap tend to be young men’s music. Young women’s music tends to be more reflective, contemplative, and introspective, more preoccupied with issues of romance, identity, family, and fitting in, but also with female empowerment.

These musical preferences appear to reflect certain psychological and developmental issues. Many young men use music to express anger and feelings about life’s unfairness, while young women use music to deal with issues of connection and longing and expression of sexuality.

Race and Music

Many ethnic groups have exerted a powerful influence on American music, including the Irish, the Germans, Jews, white Southerners, and Latinos. But no group has had a greater influence than African Americans. Repeatedly over the course of American history, African Americans have revitalized American music.

This has raised an important issue. To what extent have whites expropriated and exploited black music?

There are two ways of looking at this question. One view is that whites have stolen, appropriated, and profited from black music. Another view is that whites and blacks together have drawn on various kinds of black music to create new musical forms, different from anything that existed before.

In fact, both of these statements are true.

The History of Popular Music

Over the course of American history, American music has undergone profound changes. Here are some of the largest themes:

- Music meant to be played and sung has increasingly given way to music intended to be listened to or danced to.

- Music has been increasingly commercialized. Commercialization tends to make songs more formulaic and standardized, and therefore robs music of its freedom, elasticity, and unfettered spirit.

- In the past, many kinds of music were largely invisible to the mass audience. In the 20s, for example, most whites were totally unfamiliar with African American ragtime, blues, or jazz, much as most whites today are unfamiliar with Chicano music. For the most part, however, folk music, regional musics, and ethnic musics now reach a national audience.

- The kinds of themes in popular song seem to have narrowed. In the past there were political songs, reform songs, and work songs. Today, most songs deal with issues involving love.

The Political Economy of Popular Music

The kinds of music that dominate at particular times reflect diverse technological, legal, and economic factors.

Why, for example, are songs usually about three minutes long? Because the original recording technology—wax cylinders and 78 discs—only permitted songs of that length. During the 19th century, before the invention of the phonograph, songs were often much longer.

The Politics of Popular Music

Today, many parents and politicians worry about graphic sex, morbid violence, overt racism, and challenges to authority in popular music lyrics and videos.

In recent years, popular music has been accused of celebrating the abuse of women and the murderous power of machine guns, for encouraging satanic activity, substance abuse, and suicide. In actuality, most popular music deals with the same theme that it has for over half a century: love. But the treatment of love has changed in revealing ways. A quarter century ago, when songs like “Soldier Boy” topped the charts, song lyrics stressed eternal love to one fated partner. Today, song lyrics convey quite a different message: that while love is fun, it is often transient.

During the twentieth century, most popular music dealt with a single theme: romantic love. That music which dealt with other subjects was highly marginalized. Most middle-class listeners had virtually no exposure to it.

Lyrics and Themes

Popular music’s preoccupations have changed profoundly over time.

During the pre-Civil War era, popular music was preoccupied with nostalgia. It is no accident that the first truly popular commercial song was “Home, Sweet Home.”

The nineteenth century was filled with songs of nostalgia, contrasting a dismal present with a much better past. This strikes one as odd. Americans had left homes and homelands and friends and families and suffered a profound sense of rootlessness.

But, alongside sentimental and nostalgic songs were songs that expressed a virulent racism. Racism pervaded much of the music of the ninteenth century and intensified again around the turn of the century when an entire genre of harshly racist songs known as “coon” songs proliferated.

Most popular songs were written to be sung in the family parlor. They had a didactic as well as an artistic function.

The Roots of American Popular Music

What makes American music different from music anywhere else is that it is a product of cultural blending and mixing which has contributed to extraordinary innovation and vitality. It is an outgrowth of distinct ethnic, regional, and religious traditions.

Native American Traditions:

Like Asian music, Native American music is generally foreign to modern day Americans’ ears. It was different in sound and function than European music. It was bound up in communal ceremonies and social rituals. There were ceremonial songs, game songs, and healing songs. Music’s importance lay not in its beauty but its efficacy. It is connected to spirituality, which is not contrasted to the secular world.

Native American music was predominantly vocal; there was little purely instrumental music. Native American music emphasizes sounds rather than words. Singing is usually accompanied by drum or rattle, whistles, and flutes; there is a great deal of repetition.

English Traditions

English settlers brought a variety of musical traditions to the New World. These included love songs, such as “Black is the Color of My True Love’s Hair”; music for dancing, such as “Play Party Games,” “Skip to My Lou and Loupy Lou,” and fiddle tunes for hoedowns; these were rapid dance tunes and jigs.

But perhaps the most influential tradition was the ballad, such as Barbara Allen. Ballads recounted particular occupations, fatal physical disasters, or murders and executions. Traditionally, ballads were sung without accompanying instruments. Because these songs were passed down through oral transmission, alterations in wording and tunes were inevitable. These was a tendency to localize these songs.

African Traditions

African traditions exerted a pervasive influence on American music. During early American history, African and African American traditions included field hollers, the rhythmic chanting of work songs; breakdowns, including banjo tunes and cakewalks, praise songs, and spirituals, voodoo flavored dances, and Creole songs.

African and African American music was characterized by the dominance of rhythm and percussive instruments, a high degree of rhythmic complexity, and a perception of music as a kinetic experience, inseparable from bodily movement.

Hispanic Traditions

Hispanic traditions grew out of a blending of Iberian, Indian, and African traditions from Caribbean, Central, and South America. There was religious music, such as alabado, a religious folk song. There was Mexican secular music, such as the corrido or folk ballad, which deals with actual people and events in an earthy, frank, unembellished way. There was the cancion, which lyrical and sentimental, in contrast to the narrative, epic quality of the corrido. And there were instrumental ensembles, which would eventually produce the mariachi (including trumpets, violins, guitars, and bass guitar); and the conjunto or ensemble of the music nortena (including accordion, saxophone, guitar, trumpet—influenced by polka or waltz).

From the Caribbean and South America came such musical styles and dances as the Habanera, the Tango, Rumba, the Samba, the Mambo, the Chachacha, the Merengue, and the Bossa Nova.

Music in the Colonial Era

Music occupies an important, but little understood, place in our understanding of colonial American. The Zenger case, which helped establish the principle of freedom of the press, involved the publication of songs that had been deemed seditious. Music also provides an index to changing religious values, including the decline of Calvinism and the emergence of evangelical Protestantism.

In early modern Europe, there were several musical traditions. There was music associated with public institutions and social hierarchy, with royal courts, the nobility, and the church; and there was music, such as ballads, passed down through oral traditions or, later, through broadsides. Sung with an unaccompanied voice, many of these ballads told entertaining stories in a detached manner. Some contain grisly details or elements of the supernatural, some were humorous; many offered guides to moral behavior, and some, like “Frog Went a-Courting,” accompanied children’s games.

In seventeenth-century colonial America, the kind of music associated with courts and churches did not exist. There were very few professional musicians and most music was imports or adaptations of Old World music.

It was not until the mid-eighteenth century, with the emergence of distinct gentry and merchant classes, that concert and operatic music became common. Classical music was patronized almost exclusively by literate and educated elites, who also increasingly participated in musical societies. Many members of the colonial elite played the violin (including Jefferson), the flute (Washington), and the guitar and harp (Franklin). Opera and especially theater drew a much wider audience.

In the eighteenth century, there was also military music, circus music, ballad operas, comic operas, and pantomime, in which action and speech were accompanied by wordless music. There was also music for dancing, including the minuet, the more intricate gavotte, the cotillion, the quadrille, and the country dance, a kind of line dance. Only later, however, were there couple dances, such as the waltz.

Sacred and devotional music became increasingly important during the colonial era. In the seventeenth-century, psalms, rather than Lutheran chorale or Catholic music, dominated religious music. Most European colonists brought an aversion to state religion and temporal ecclesiastical hierarchy and power, summed up in the word “popery.”

Music in Calvinist churches was limited to unaccompanied unison singing of psalms, to ensure that the music was subordinate to worship itself. The psalms were sung by entire congregations, not trained choirs.

The first printed book in English colonies was The Whole Book of Psalmes (1640), which contained no music. Not until the ninth edition was published in 1698 did the volume contain musical notation. In New England, in particular, there was a strong prejudice against instrumental music in churches.

Over time, the singing of psalms grew more disorderly. The pace of music became slower and more erratic. To address this problem, churches adopted the practice of “lining out,” a deacon or pastor would recite each line before it was sung.

Around 1720, this older form of singing (known as the “Usual Way”), was challenged. Reformers, usually literate urban people, promoted “Regular Singing,” including separate choirs and the singing of hymns and the use of written music, which required instruction by a master and the emergence of the singing-school. The first organized musical instruction was offered in 1719 in Virginia. Some singing masters, such as William Billings (1746-1800), became composers. Hymns, canons (rounds), fuging tunes, anthems and set pieces for special occasions were introduced. By 1810, three-hundred tunebooks had been published.

Music in the New Nation

Following the Revolution Americans began to produce distinctively American songs fashioned out of the elements of several different ethnic styles. In 1778, the Continental Congress prohibited theatrical productions on the grounds that “frequently Play Houses and theatrical entertainments, has a fatal tendency to divert the minds of people from a due attention to the means necessary for the defence of their country and preservation of all liberties.” After the ban was lifted in 1789, music publishers appeared in many American towns and a growing number of immigrant musicians arrived in the United States.

Unlike British songs of the period, which tended to be humorous or bawdy, the most influential early American indigenous songs dealt with more serious subjects, such as war, slavery, separation of loved ones, and liberty.

During the early nineteenth century, the market for musical entertainment expanded enormously. There was a growing popular market for sheet music, theaters. A new kind of variety show that predated vaudeville, called the olio, appeared. Meanwhile, circuses incorporate comic song and dance acts. But it would be the minstrel show that exerted the most powerful impact on American music.

To hear examples of the varieties of early American music you can visit the University of Virginia Music in American Life website.

Irish Melodies

Irish Protestant and Catholic immigrants exerted a powerful influence on the music of the new republic. They carried a rich store of ballads, dances, and songs. Especially influential was a multi-volume collection of Irish songs known as Irish Melodies. Its songs—melancholy and sentimental—share the distinction with the songs of Stephen Foster as being the most popular, widely sung, best loved, and most durable songs of the entire nineteenth century.

It may seem strange that Americans were attracted to nostalgia in their music. The explanation is that many Americans had left homes and homelands and friends and families and suffered a profound sense of rootlessness and dislocation.Nostalgia was a dominant theme in many Irish songs, and this thread would characterize much of the music of nineteenth century America, which dealt with a longing for a lost home, for childhood, and friends. The most popular American song of the nineteenth century was “Home, Sweet Home”, based on a text by the American poet, John Howard Payne.

Italian Opera

Beginning in the second decade of the nineteenth century, Italian opera began to exert a powerful influence on American song. Today, we draw a sharp distinction between high culture and popular culture, but that was not the case in the early nineteenth century. Ordinary Americans sang opera songs in their parlors and even danced to them.

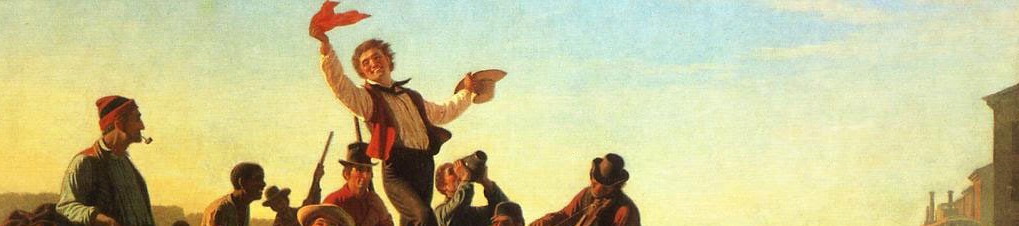

Minstrelsy

It is sad but true that the first truly indigenous American music is associated with the black-faced minstrel show. Impersonation of blacks by whites has a long history, but in the 1840s, it became the most popular form of stage entertainment in America. Minstrel shows included caricature; songs dances, jokes, satirical speeches, and skits.

There can be no question that the minstrel shows served to justify slavery and racial inequality. Thomas Dartmouth Rice (1808-1860) dressed in shabby clothing, and performed grotesque, disjointed dances. George Washington Dixon (1801-1861) sang Zip Coon (which we now know as Turkey in the Straw), dressed as a dandy, wearing a high hat, yellow waistcoat, light colored breeches, fashionable swallowtail coat, carrying a watch, wearing jewelry, and twirling a pince-nez. Grossly disproportioned, he was a figure of ridicule and laughter.

Minstrel shows emphasized racial caricature and vicious stereotypes. But, the minstrel was not simply a demeaning portrayal. He was ambiguous, even paradoxical, like other figures of burlesque. He satirized pretentious upper-class and other whites.

Stephen Foster

It was the minstrel show that popularized the music of the most influential American composer of the nineteenth century, Stephen C. Foster. He was, appropriately, born on the fourth of July on the fiftieth anniversary of American independence. His music combined Irish, Scottish, and African American traditions, and included fast-paced comic tunes and slow sentimental songs. Over time, apparently, Foster increasingly grew disturbed by slavery. He dropped dialect, and paid greater attention to the costs of slavery, a theme evident in his song “Old Folks at Home.”

Music and Reform

Throughout American history, music has often served to promote reform movements. This was especially true during America’s first age of reform in the 1830s, 1840s, and 1850s. There were songs attacking drink and many songs critiquing slavery. The Hutchinson Family was the most influential singing group to use popular song as a vehicle of political and social protest.

Making Ethical Judgments

Should the United States Change Its National Anthem?

Does the United States need a new national anthem? That is the question some are asking after learning that Francis Scott Key, the author of the song that celebrates the United States “as the land of the free and the home of the brave” was a slaveowner. His critics call him a defender of slavery, an opponent of abolition, and an enemy of free speech, and deem his song, racist and militaristic.

Is it time to dump the national anthem—a song, one newspaper, declared, with “words that nobody can remember [set] to a tune that nobody can sing”?

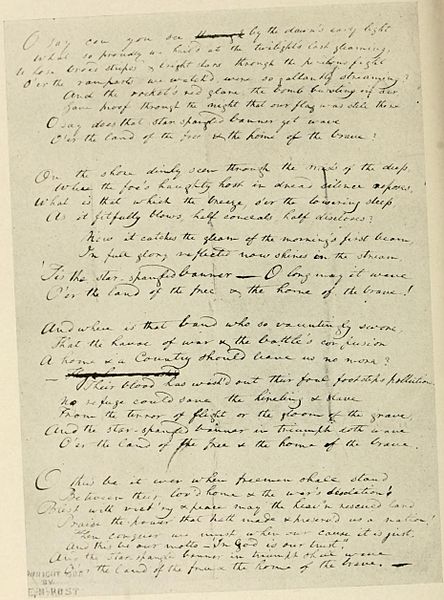

Especially disturbing to critics of the “Star-Spangled Banner” is its seldom sung third stanza, which says, in part:

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave.

This was a reference to the enslaved African Americans and poor whites who fought alongside the British Army during the War of 1812. Such traitors, the song implied, should suffer a well-deserved death.

Abolitionists altered Key’s words and called America the “Land of the Free and Home of the Oppressed”

The Star-Spangled Banner’s backstory is well-known. During the War of 1812, British troops set fire to the White House in retaliation for an American attack on the city that would become Toronto. Already, British forces had ravaged the surrounding countryside. Hundreds of enslaved African Americans fled their masters, with some joining the British navy and others fleeing to freedom in Bermuda, Nova Scotia, and Trinidad.

Key, who was attempting to negotiate the release of several American prisoners of war, was detained on a British warship. Over the course of twenty-five hours on September 13 and 14, 1814, the British fleet bombarded Fort McHenry, which guarded Baltimore. At dawn, the fort’s flag still waved—a sight that inspired Key to write a poem which was soon set to a widely known tune that had originated as a British drinking song (but which was also widely used for patriotic purposes).

Key was himself a man of many contradictions. As one of the founders of the American Colonization Society, he advocated resettling free blacks in Africa, in Liberia, a colony founded in 1820-1821. The motives of colonizationists were mixed: To encourage slaveowners to voluntarily free their slaves, to remove free blacks from the United States, and to promote the development and Christianization of West Africa.

After a slave ship, the Antelope, was captured off the coast of Florida in 1820, Key would argue before the Supreme Court that the ship was engaged in piracy and that the 258 captives on board should be returned to Africa. (The Court ultimately returned 120). In a number of other cases, Key represented enslaved blacks in court pro bono, arguing that a 1783 Maryland law prohibited slaveowners from bringing slaves into the state. In one instance, he prevented a white mob from lynching a nineteen year old accused of attempted murder.

But, Key also expressed abhorrent racist sentiments, and once called Africans in America “a distinct and inferior race of people, which all experience proves to be the greatest evil that afflicts a community.” During the 1830s, while serving as District Attorney in Washington, he brought charges of seditious libel against abolitionists, in one instance for bringing antislavery publications into the District of Columbia.