The First New Nation

The Federalist Era

In 1789, it was an open question whether the Constitution was a workable plan of government. It was unclear whether the new nation could establish a strong national government, a vigorous economy, or win the respect of foreign nations. For a decade, the new nation battled threats to its existence, including serious disagreements over domestic and foreign policy and foreign interference with American shipping and commerce.

During the initial twelve years under the new Constitution, the Federalists established a strong and vigorous national government. Alexander Hamilton’s economic program attracted foreign investment and stimulated economic growth. The creation of political parties was an unexpected development that involved the voting population in politics. Presidents George Washington and John Adams succeeded in keeping the nation free from foreign entanglements during the nation’s first crucial years.

Despite bitter party battles, threats of secession, and foreign interference with American shipping and commerce, the new nation had overcome every obstacle it had faced.

James Thomson Callender, Scandalmonger

He was the new republic’s most notorious scandalmonger. During the 1790s, James Thomson Callender published vicious attacks on George Washington, John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, and other leading political figures. Today, he is best known as the journalist who first published the story about Thomas Jefferson’s decades-long affair with one of his slaves.

Born in Scotland in 1758, Callender was an early advocate of Scottish independence from Britain. After being indicted for sedition, he fled to Philadelphia in 1793, where he supported himself as a journalist and political propagandist.

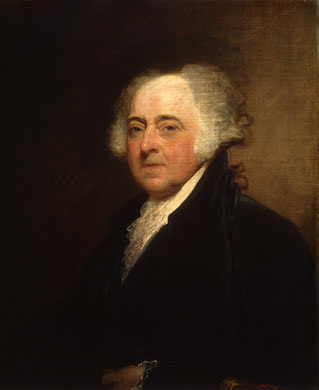

In 1798, Hamilton’s political party, the Federalists, pushed the Sedition Act through Congress, making it a crime to attack the government or the president with false, scandalous, or malicious statements. In 1800, Callender was one of several journalists indicted, tried, and convicted under the law. He was fined $200 and sentenced to nine months in prison.

Profoundly suspicious of Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton’s pro-British views on foreign policy, Callender used his pen to discredit Hamilton. In 1797, he published evidence that Hamilton had an adulterous extramarital affair with a woman named Maria Reynolds. Callender also accused Hamilton of misusing government funds. Hamilton acknowledged the affair, but denied the corruption charges, claiming that he was a victim of blackmail. Nevertheless, Hamilton’s public reputation was tarnished, and he never held public office again.

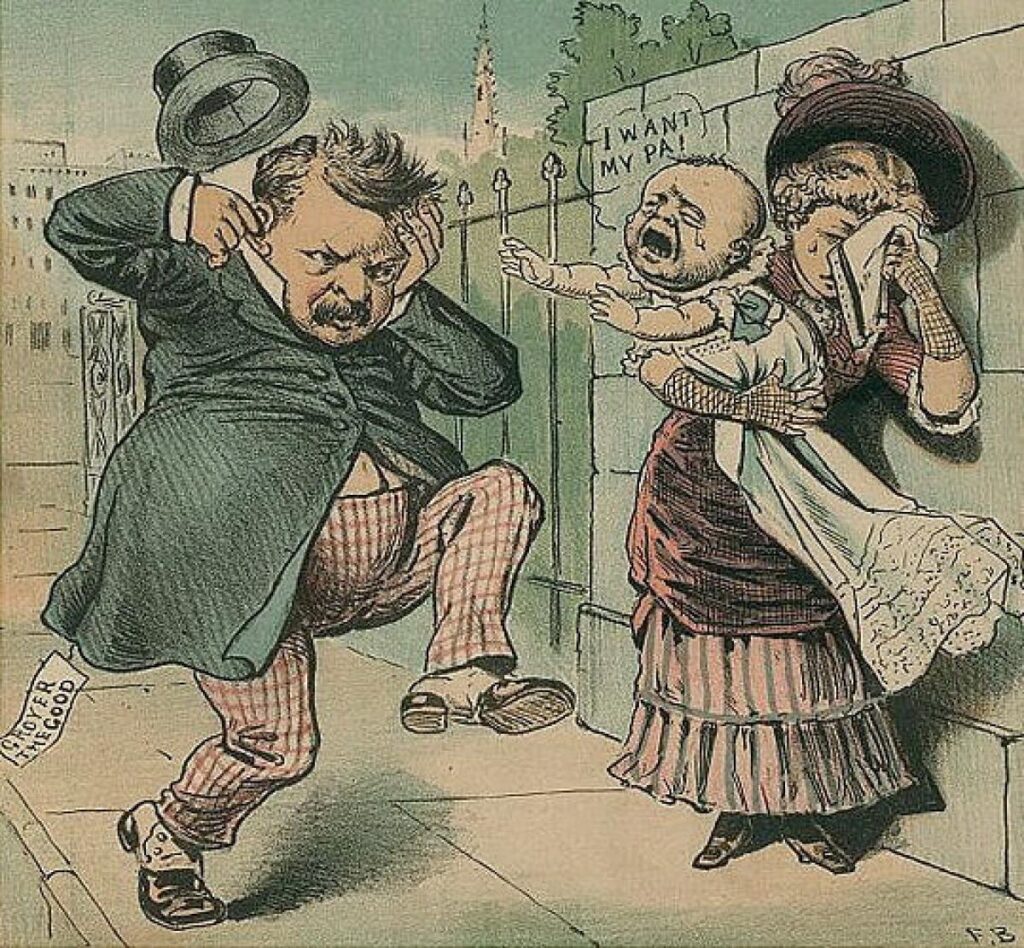

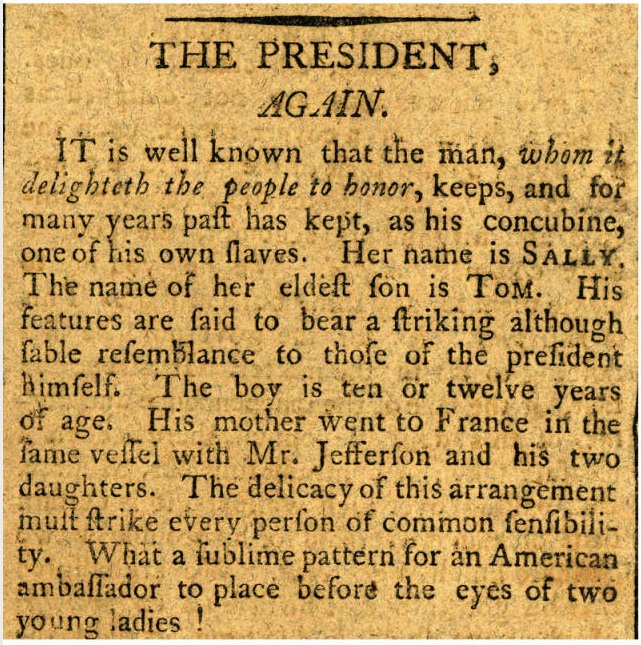

By the time he was released, Thomas Jefferson had been elected president. Callender expected the new administration to appoint him as a postmaster. When Jefferson refused, Callender struck back. In 1802, he publicly accused Jefferson of having a lifelong liaison with his slave, Sally Hemings. Soon afterward, Callender drowned in three feet of water.

Sally Hemings was the half-sister of Jefferson’s deceased wife, Martha. Her mother had been impregnated by her master, John Wayles, the father of Martha Jefferson. Sally Hemings herself bore five mulatto children out of wedlock. Callender insisted that Jefferson fathered the children. Jefferson’s defenders denied this. DNA testing in 1998 indicated that Jefferson fathered at least one of the Hemings children.

Attacked by his critics as a “traitorous and truculent scoundrel,” Callender defended himself on strikingly modern grounds: that the public had a right to know the moral character of people it elected to public office. Although he has often been dismissed as a “pen for hire,” willing to defame anyone, Callender was much more important than that.

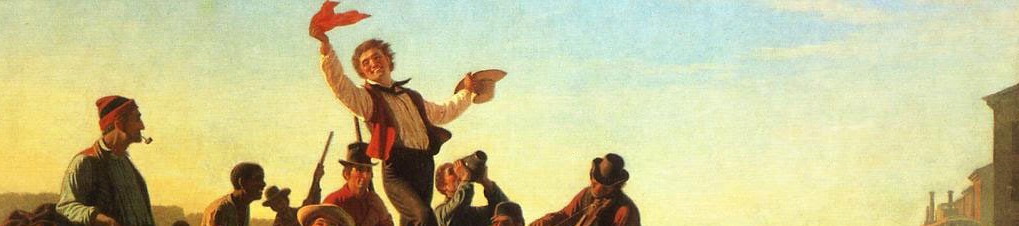

His life underscored one of the most radical consequences of the American Revolution. The Revolution ensured that ordinary Americans would be the ultimate arbiters of American politics. Callender aimed his political commentary at artisans and immigrants who flocked to seaport towns during the 1790s. As one of the first modern journalists, he appealed to these people with scandal, sensation, and suspicion of the powerful.

Podcast

Political Scandal in Historical Perspective

Listen to “Political Scandal in Historical Perspective.”