Ratifying the Constitution

Ratifying the Constitution

The Constitution encountered stiff opposition. The vote was 187 to 168 in Massachusetts, 57 to 47 in New Hampshire, 30 to 27 in New York, and 89 to 79 in Virginia. Two states, North Carolina and Rhode Island, refused to ratify the new plan of government.

Those who opposed the adoption of the Constitution were known as the Anti-Federalists. Many feared centralized power. Many doubted the ability of Americans to sustain a continental republic. Some Anti-Federalists were upset that the Constitution lacked a religious test for office holding. Others were concerned that the Constitution failed to guarantee a right to counsel and a right not to incriminate oneself in criminal trials, or to prohibit cruel and unusual punishments.

Several arguments were voiced repeatedly during the ratification debates:

- That the Convention had exceeded its authority in producing a new Constitution.

- That the Constitution established the basis for a monarchical regime.

- That the Constitution lacked explicit protections for individual and states’ rights.

Some Anti-Federalists saw no need for the Constitution’s intricate system of separation of powers. Some wanted to know whether the elastic clause would sanction a broad interpretation of national powers at the expense of the states.

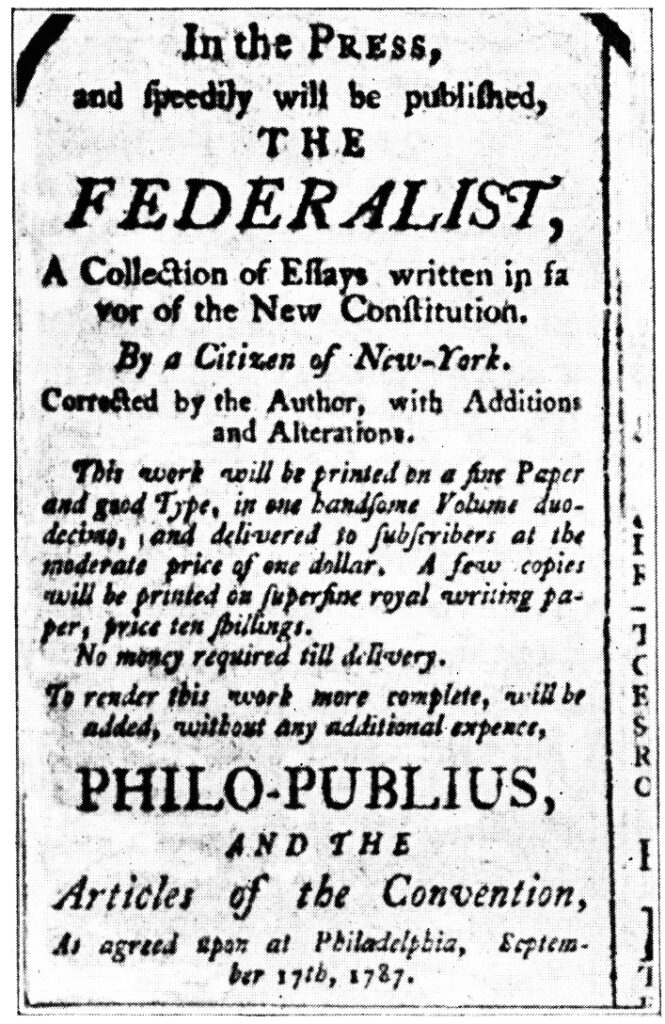

From October 1787 to March 1788, Madison, Hamilton, and John Jay wrote a series of 85 essays that appeared in New York newspapers. In these essays, they argued that the powers of the national government were distributed and balanced in a way that would sustain limited government. They also argued that there were sufficient guarantees to ensure that the national government respect the boundaries of state authority and that individuals would be secure against federal encroachments.

In the end, even some of the most outspoken Anti-Federalists, like Melancton Smith of New York, ultimately voted for the Constitution. They feared that the only alternative to the Constitution was the breakup of the Union.

Forecasting the Future

The Bill of Rights

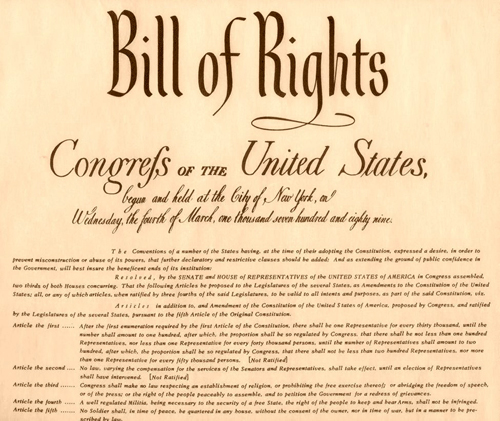

Seven states had bills of rights protecting fundamental freedoms from government infringement. Among the rights that were guaranteed were freedom of the press, of speech, and of religion, and the right to a jury trial.

The Constitutional Convention did include specific protections in the Constitution. Article VI restricted government interference with religion and speech. It also provided certain protections in criminal law. It guaranteed that the writ of habeas corpus (a protection against illegal imprisonment) “shall not be suspended” except in times of rebellion or invasion. It also prohibited bills of attainder (imposing punishment on a person’s descendants) and ex post facto laws (laws that punish behavior that took place before their enactment). It also forbade any state to pass laws “impairing the obligation of contracts.”

George Mason, the main author of Virginia’s 1776 Declaration of Rights, wished that the Constitution “had been prefaced with a bill of rights.” But James Madison felt a bill of rights was unnecessary and superfluous. He feared that by specifying certain rights for protection might suggest that other rights might be tampered with. He also worried that such protections would be insufficient “on those occasions when control is most needed.”

But pressure for a Bill of Rights was intense. Thomas Jefferson wrote Madison: “…a bill of rights is what the people are entitled to against every government on earth, general or particular, and what no government should refuse or rest on inference.” During the ratification debates, the Constitution’s supporters agreed to adopt a Bill of Rights.

State ratification conventions proposed more than two hundred proposed amendments. From these, Madison distilled nineteen possible amendments. Congress accepted twelve of the Amendments and the states approved ten. One of the rejected amendments dealt with the size of the House of Representatives. The other amendment restricted Congress’ ability to increase its salary. Salary changes cannot take effect until after the next congressional election. This amendment was ratified in 1992.

During the nineteenth century, the impact of the Bill of Rights was limited. In the 1833 case of Barron v. Baltimore, the Supreme Court ruled that the Bill of Rights only protects individuals from the national, and not the state, governments. It was the 14th Amendment, adopted in 1868, that applied the Bill of Rights to the states.

The First Ten Amendments

I. Freedom of Religion, Speech, and the Press, and the Right of Assembly and to Petition Government

The First Amendment prohibits Congress from creating an established church. It has been interpreted to forbid government support for religious doctrines. The amendment also prohibits Congress from passing laws to restrict worship, speech, the press, or to prevent people from assembling peacefully. In addition, Congress may not prevent people from petitioning the government.

II. Right to Bear Arms

The Second Amendment has been interpreted by some to give citizens the right to possess firearms. Others believe it grants the states the right to maintain their own militias.

III. Billeting of Soldiers

The Third Amendment forbids the government from housing soldiers in homes in peacetime without their owners’ consent.

IV. Searches and Seizures

The Fourth Amendment requires legal authorities to obtain a search warrant before conducting a search of a person’s possessions.

V. Rights in Criminal Cases

The Fifth Amendment says that no one can be tried for a federal crime unless he or she is indicted by a grand jury, a group of citizens who decided whether there is sufficient evidence to put the person on trial. The amendment also states that a person cannot be tried twice for the same offense (unless the jury fails to reach a verdict). The amendment guarantees that individuals cannot be required to testify against themselves and cannot be deprived of “life liberty or property, without due process of law.” The amendment also forbids government from taking a person’s property for public use without fair payment.

VI. Rights to a Fair Trial

The Sixth Amendment guarantees a person accused of a crime the right to a “speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury” in the jurisdiction where the alleged crime was committed. The Amendment also guarantees that accused persons will be informed of the charges against them and that they have the right to cross-examine witnesses and to have a lawyer to defend them.

VII. Rights in Civil Cases

The Seventh Amendment guarantees the right to a jury trial in civil lawsuits.

VIII. Bails, Fine, and Punishments

The Eighth Amendment prohibits excessive bail or fines and “cruel and unusual” punishments.

IX. Rights Retained by the People

The Ninth Amendment ensures that rights unmentioned in the Bill of Rights are protected.

X. Powers Retained by the States and the People

The Tenth Amendment ensures that the powers not delegated to the federal government are retained by the states and the people.

Historical Debates

Was the Constitution Consistent with the Nation’s Revolutionary Values?

The question of whether the proposed Constitution was consistent with republican government dominated the ratification debates. The Constitution’s critics, who are known as the Anti-ederalists, objected to the new framework of government on several grounds. Some feared that unless Senators and Representatives were barred from reelection, they would become a corrupt, entrenched oligarchy. Others worried that it would be impossible for two distinct governments—a federal government and state governments–to operate simultaneously over the same territory.

The Anti-Federalists were a disparate group. They included prominent leaders, such as Samuel Adams (1722-1803) and Patrick Henry (1736-1799) who feared that the Constitution lacked sufficient safeguards to protect the rights of individuals and the states. There were also many ordinary farmers, small shopkeepers, and artisans who feared giving the federal government authority over taxes and commerce. Convinced that republicanism depended on government close to the people, such individuals worried that the Constitution transferred control of local affairs to a remote central government, a government which would be controlled by elites. This was an argument easily exploited by local elites who feared any dwarfing of their own power.

Many concerns were voiced during the ratification debates, including such matters as the length of terms of senators and the president and the danger of a federally-controlled military. But the issue that prompted the most concern was the absence of a written bill of rights. In Massachusetts, New York, and Virginia, opposition to the proposed Constitution was particularly significant. But because the framers ultimately agreed to add a bill of rights, which was actually adopted during the first Congress in 1791, the United States never developed the kind of on-going anti-constitution tradition that would be found in other countries such as France.

History Through…

…Primary Sources

The following document examines whether the Constitution was consistent with republican principles of government.

“To expect…unanimity in points of so great magnitude…was contrary to all experience”

Writing two weeks after the Convention of 1787 adopted the Constitution, Benjamin Rush (1746-1813), a signer of the Declaration of Independence and the new nation’s leading physician described the Constitution as a “masterpiece of human wisdom.” I now look forward to a golden age in America,” he wrote. “The new Constitution realizes every hope of the patriot & rewards every toil of the hero.” His only misgiving was that he wished the Convention “had gone further, & absorbed more of the power of our State governments.”

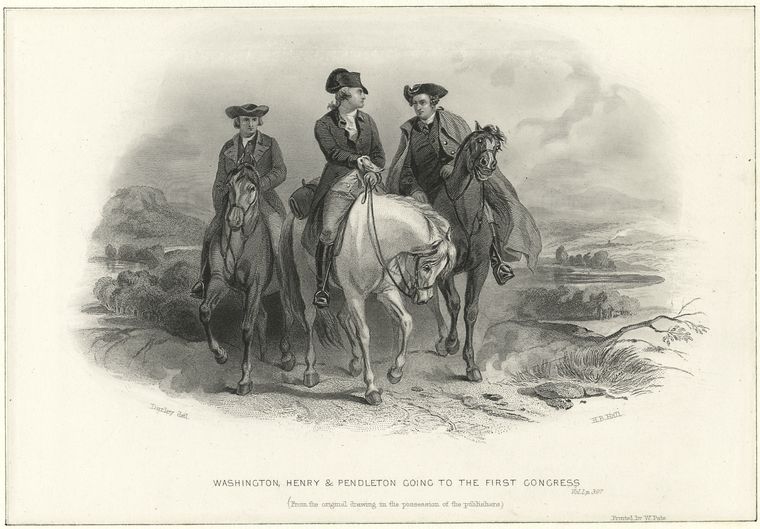

In the following letter to James Madison, the “Father of the Constitution,” the Virginia jurist Edmund Pendleton (1721-1803) offers his careful and candid appraisal of the new Constitution.

Edmund Pendleton to James Madison, October 8, 1787,

To expect individual or even state unanimity in points of so great magnitude and difficulty, was contrary to all experience, and to maintain one’s opinion by all the arguments which reason and mental powers afford, is manly & becoming whilst the subject is in agitation & suspense; but to yield to the decision of a majority, when further opposition can have no good, & may produce many bad effects, is not only commendable, but in my opinion an individual duty….

I began to read it with two impressions on my mind, with which I think every reader of it should set out. 1st. That something was necessary to be done, and that a plan, very far short of perfection, was greatly preferable to our present condition, and which would probably have been considered as desperate, if the Convention had risen without doing anything. 2nd. That in Governments as well as other things, perfection is unattainable, and indeed attempts to approach it, by too much refinement, generally produce more mischief than good….

A Republic was inevitably the American form, and its natural danger popular tumults & convulsions. With these in view I read over the Constitution accurately and do not find a trait of any violation of the great principles of the form, all power being derived mediately or immediately from the people; no titles or powers that are either hereditary or of long duration so as to become inveterate…. The people, the origin of power by representation–the [members of the House of Representatives]…are to consist of their immediate choice, and the choice of the Federal Senate and President, seems admirably contrived to prevent popular tumults, as well to preserve the equilibrium expected from balancing power of the three branches. In the power of negation [the President’s veto power, which can be overridden by two-thirds vote of both houses of Congress] to the laws, the modification strikes out a happy balance between an absolute negative in a single person, and having no stop & cheque upon laws too hastily passed….

The President is indeed to be a great man, but ’tis only to represent the Federal dignity & power, having no latent prerogatives, any powers but such as are defined & given him by law. He is to be Commander in Chief of the Army & Navy, but Congress are to raise & pay them, and that not for above two years at a time. He is to nominate officers, but Congress must first create the offices & fix them and may discontinue them at pleasure, & he must have the consent of two-thirds of the Senate to his nomination. Above all his tenure of office is short, & the danger of impeachment a powerful restraint against abuse of office. A political head and that adorned with powder’d hair, seem necessary & useful in government…; and I have observed in the history of the United Netherlands, their affairs always succeeded best, when they allowed their [official] to exercise his Constitutional powers….

The line between Federal and State powers, the most difficult part of the work, appears to me most happily drawn, and I much applaud that spirit of amity and concession which produced, and which I hope may continue to perfect it. In the regulations of commerce however, I shall hope not to see projects introduced for discouraging foreign trade, or driving us too soon into manufactures, in favor of which our presses have groaned under labour’d nonsense in the course of this summer. Trade & manufactures should both be free, and will make their way in proper time….

My last criticism you will probably laugh at, tho’ it is really a serious one with me. Why require an oath from public officers, and yet interdict all religious tests, their only sanction? Those hitherto adopted have been narrow & illiberal, because designed to preserve established modes of worship; but since a belief of a future state of rewards & punishments, can alone give conscientious obligation to observe an oath, it would seem that test should be required or oaths abolished.

It is time I had done with my trifling observation, with which & a thousand others more material, you had been sufficiently tried at Phil[adelphi]a, I will only add my warmest thanks as an individual to the authors of the work of their labours, & declare my unequivocal acceptance of it, with all it’s imperfections.