Drafting the Constitution

Drafting the Constitution

For nearly four months during a hot, muggy Philadelphia summer, the delegates debated thorny issues:

- Should the national government be allowed to veto state laws;

- Should the states be eliminated altogether;

- Should there be a single president or an executive committee.

Framing the debate was a plan introduced by Edmund Randolph, the governor of Virginia, but actually written by James Madison. The Virginia Plan proposed a national legislature divided into two houses, the House of Representatives and the Senate.

- Individual voters, not state governments, would elect members of the House of Representatives.

- Representation in both houses of Congress would be based on population.

- Members of the House would select members of the Senate (from candidates suggested by state legislatures), judges, and a president, who would serve for seven years.

- Congress would have the power to veto state laws.

Delegates from small states protested that the Virginia Plan would give larger states too much power in the national government. New Jersey proposed that all states have an equal number of representatives. Under the New Jersey Plan, Congress would consist of only one house, to be elected by the state legislatures, not the people. The New Jersey Plan received support from Delaware, New Jersey, and New York. The Maryland delegation split.

Several of Madison’s proposals were defeated. The delegates eliminated a congressional veto over state legislation. They also abandoned his notion of apportioning representation in both houses of the legislature on the basis of population.

Compromises

The Constitution was a product of compromises, some of which succeeded brilliantly and others that left an enormous burden to the generations that followed.

Over the course of the debates, the delegates reached agreement on certain fundamental principles. They achieved a consensus that in a republican government, power should be divided among three separate branches—legislative, executive, and judicial, a principle enshrined in most state constitutions.

They also agreed that: the central government should have direct power to tax; the new House of Representatives should be elected directly by the people; there should be periodic elections; the national government should have the sole power to regulate interstate and foreign trade.

They rejected Benjamin Franklin’s suggestion that public servants should receive no salary. They also rejected a proposal for an executive branch composed of three persons. One-year terms for members of the House were voted down out of concern that members would spend all their time traveling. Three-year terms were rejected for fear members would lose touch with their constituencies. The discussion on the length of term for the president proved difficult to resolve. Proposals ranged from three years to twenty years. To insure that the poorer states could not tax the richer states, the Constitution provided that the House of Representatives had exclusive authority to originate bills raising revenue.

Completing a Final Draft

In late July 1787, a five-member Committee of Detail was given the task of arranging and organizing the Constitution and choosing its wording. The members of the committee were James Wilson from Pennsylvania; John Rutledge of South Carolina, Nathaniel Gorham of Massachusetts, Oliver Ellsworth of Connecticut, and Edmund Randolph of Virginia.

The committee decided that the Constitution would contain “essential principles only; lest the operations of government should be clogged by rendering those provisions permanent and unalterable which ought to be accommodated to times and events.” The members vowed to use “simple and precise language” and “general propositions” rather than intricate detail.

The committee first prepared an outline, consolidating the convention’s decisions by category: the legislative, the executive, and the judiciary. It gave the names to the institutions of government: the Congress, the Supreme Court, and the President of the United States. It listed the powers of each branch and qualifications for office.

The committee enumerated eighteen powers for Congress, from the power to tax to the power to regulate commerce and make war. The eighteenth power, known as the “elastic clause,” gave Congress the authority “to make all laws that shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers and all other powers vested by this Constitution in the government of the United States.” The committee members also included a “supremacy clause,” which made federal law supreme to “anything in the Constitution or laws of any state to the contrary notwithstanding.”

When the committee had completed its assignment, the Convention reopened debate, and made dozens of changes throughout the draft Constitution.

- To decrease presidential power, the convention reduced the vote required to override a presidential veto from three-fourths of each house to two-thirds.

- To make it easier to remove a corrupt president, the convention expanded the grounds of impeachment, adding high crimes and misdemeanors to treason and bribery, which had been approved earlier.

- A provision requiring Congress to call a constitutional convention on the application of two-thirds of the states was added.

The power to appoint judges and ambassadors and to negotiate treaties with foreign powers was in the hands of the Senate until the last weeks of the convention. Then the convention decided that the president would nominate judges and ambassadors and the Senate would have to confirm them. The executive branch would negotiate treaties, with the advice and consent of the Senate.

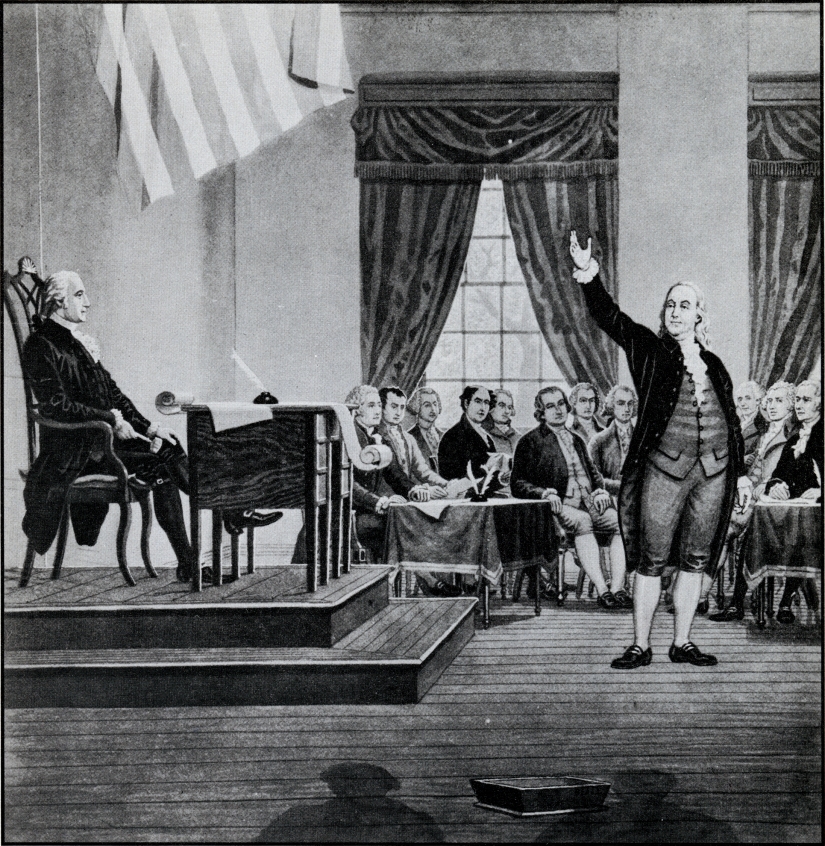

In an effort to generate support for the new plan of government, Benjamin Franklin said:

I confess that there are several parts of this Constitution which I do not at present approve…. [But] the older I grow, the more apt I am to doubt my own judgment, and to pay more respect to the judgment of others…I consent, sir, to this Constitution because I expect no better, and because I am not sure that it is not the best.

Although a number of individual delegates refused to sign the Constitution, all the state delegations voted for the final draft.

While they were signing, Franklin commented about the chair on the days in which the Convention president had sat. Franklin said he had been studying the chair, which had a sun painted on the headrest. He had often looked at the sun “”without being able to tell whether it was rising or setting. But now at length I have the happiness to know that it is a rising and not a setting sun.”

The U.S. Constitution and the Organization of the National Government

The U.S. Constitution created a system of checks and balances and three independent branches of government.

The Legislative Branch

Article I of the Constitution established Congress. The framers of the Constitution expected Congress to be the dominant branch of government. They placed it first in the Constitution and assigned more powers to it than to the presidency. Congress was given “all legislative powers,” including the power to raise taxes, to coin money, to regulate interstate and foreign commerce, to promote the sciences and the arts, and to declare war.

The Executive Branch

Article II of the Constitution created the presidency. The president’s powers were stated more briefly than those of Congress. The president was granted “Executive Power,” including the power “with the Advice and Consent of the Senate,” to make treaties and to appoint ambassadors. The president was also to serve as Commander in Chief of the army and navy.

In delegate James Wilson’s view, the presidency was “the most difficult [issue] of all on which we have had to decide.” Americans had waged a revolution against a king and did not want concentrated power to appear in another guise. The delegates had to decide whether the chief executive should be one person or a committee; whether the president should be appointed by Congress; and how long the chief executive should serve.

On August 18, 1787, a Pennsylvania newspaper carried a leaked report from the Constitutional Convention. It was the first word on the proceedings that directly quoted a delegate. “We are well informed” of “reports idly circulating, that it is intended to establish a monarchical government…. Tho’ we cannot, affirmatively, tell you what we are doing, we can, negatively, tell you what we are not doing—we never once thought of a king.”

The conflict with royal governors had made the public deeply distrustful of powerful executives. Alexander Hamilton argued for a chief executive to be given broad powers and elected for life. Edmund Randolph of Virginia thought executive power should not be put into the hands of a single person since a single executive would be “the fetus of monarchy.”

To ensure a check on presidential power, Congress was given the power to override a presidential veto and to impeach and remove a president. Congress alone was given the power to declare war.

The Judicial Branch

Article III of the Constitution established a Supreme Court.

The Constitution does not specify the size of the Supreme Court. Over the years, the designated size of the Supreme Court has varied between six, seven, nine, and even ten members. Nor does the Constitution explicitly grant the courts the power of judicial review—to determine whether legislation is consistent with the Constitution.

Today, no other country makes as much use of judicial review as the United States. Many of our society’s policies on racial desegregation, criminal procedure, abortion, and school prayer are the product of court decisions. The concept of judicial review was initially established on the state-level and in the debates over the ratification of the Constitution.

In contrast to Britain, American judges do not wear wigs. When the Supreme Court held its first session in 1790, one justice did arrive wearing a wig. But the public expressed derision at wig wearing, and the justice decided that republican judges should not wear wigs.

Voting Rights

The Constitution included no property qualifications for voting or office holding like those found in the state constitutions drafted between 1776 and 1780. In a republican society, office holding was supposed to reflect personal merit, not social rank.

The Constitution did not bar anyone from voting. It only said that voting for members of the House of Representatives should be the same in each state as that state’s requirements for voting for the most numerous branch of the legislature. In other words, qualifications for voting were left to the individual states. The New Jersey constitution allowed women to vote if they met the same property requirements as men.