The Critical Period

The Critical Period

Having won the America Revolutionary War and having negotiated a favorable peace settlement, the Americans still had to establish stable governments. Between 1776 and 1789 a variety of efforts were made to realize the nation’s republican ideals. New state governments were established in most states, expanding voting and office holding rights. Lawmakers let citizens decide which churches to support with their tax monies. Several states adopted bills of rights guaranteeing freedom of speech, assembly, and the press, as well as trial by jury.

Western lands were opened to settlement. Educational opportunities for women increased. Most Northern states either abolished slavery or adopted a gradual emancipation plan, while some Southern states made it easier for slave owners to manumit individual slaves.

But all was not well. Older textbooks described the 1780s as the “critical period” of American history. The country, saddled with a wholly inadequate framework of government, was faced by grave threats to its independence:

In domestic affairs:

- The national government was on the verge of bankruptcy and the nation’s currency was virtually worthless.

- Continental Army officers threatened military action against Congress.

- Armed mobs in Massachusetts closed courts and threatened a state armory.

- States imposed heavy duties on neighboring states and enacted laws violating the rights of creditors.

In foreign affairs:

- North African pirates enslaved American sailors.

- Britain, in violation of the peace treaty ending the Revolution, refused to evacuate its forts on American soil.

- Spain conspired with Westerners, including the famous frontiersman Daniel Boone.

The label the “critical period” was exaggerated. The 1780s also established the foundation for future economic and geographical growth. Many farmers made a decisive shift away from subsistence farming toward commercial agriculture. One state—Massachusetts–chartered more corporations during the 1780s than existed in all of Europe.

Nevertheless, by 1787, many of the new nation’s leaders were convinced that the success of the American Revolution was at risk. They were especially concerned that the tyrannical majorities in state legislatures threatened fundamental freedoms, including freedom of religion and the rights of property holders. Concern for the new nation’s political stability led leading revolutionary leaders to draft a new Constitution in 1787, which worked out compromises between large and small states and between northern and southern states.

The Articles of Confederation

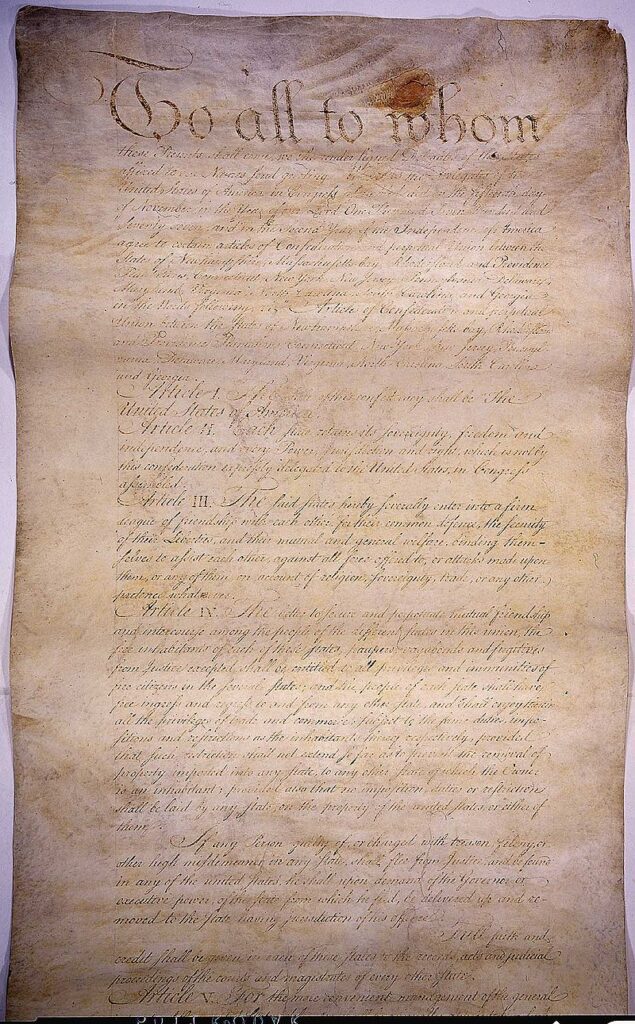

The Articles of Confederation was the United States’ first constitution. Proposed by the Continental Congress in 1777, it was not ratified until 1781.

The Articles represented a victory for those who favored state sovereignty. Article 2 stated that “each State retains its sovereignty, freedom and independence, and every power…which is not…expressly delegated to the United States.…” Any amendment required unanimous consent of the states.

The Articles of Confederation created a national government composed of a Congress, which had the power to declare war, appoint military officers, sign treaties, make alliances, appoint foreign ambassadors, and manage relations with Indians. All states were represented equally in Congress, and nine of the 13 states had to approve a bill before it became law.

Under the Articles, the states, not Congress, had the power to tax. Congress could raise money only by asking the states for funds, borrowing from foreign governments, or selling western lands. In addition, Congress could not draft soldiers or regulate trade. There was no provision for national courts.

The Articles of Confederation did not include a president. The states feared another George III might threaten their liberties. The new framework of government also barred delegates from serving more than three years in any six-year period.

The Articles of Confederation created a very weak central government. It is noteworthy that the Confederation Congress could not muster a quorum to ratify on time the treaty that guaranteed American independence, nor could it pay the expense of sending the ratified treaty back to Europe.

The Articles’ framers assumed that republican virtue would lead states to carry out their duties and obey congressional decisions. But the states refused to make their contributions to the central government. Its acts were “as little heeded as the cries of an oysterman.” As a result, Congress had to stop paying interest on the public debt. The Continental army threatened to mutiny over lack of pay.

A series of events during the 1780s convinced a group of national leaders that the Articles of Confederation provided a wholly inadequate framework of government.

The Threat of a Military Coup

Following the British surrender at Yorktown, Washington moved 11,000 Continental Army soldiers to Newburgh, New York. By 1783, the Army was near the point of mutiny over Congress’s failure to pay them. In March, Continental Army officers, camped at Newburgh, New York, considered military action against the Confederation Congress. On March 15, Washington strode in. “Do not open the flood gates of civil discord,” he told them, “and deluge our rising empire in blood.” Washington strongly believed that the military needed to be subordinate to civilian authority.

On a 90-degree June day in 1783, former Revolutionary War soldiers, carrying muskets, marched on the Philadelphia statehouse where Congress was meeting. They threatened to hold the members hostage until they were paid back wages. When Congress asked Pennsylvania to send a detachment of militia to protect them, the state refused, and the humiliated Congress temporarily relocated, first in Princeton, New Jersey, and later in Annapolis, Maryland, and New York City, New York.

Economic & Foreign Policy Problems

The Revolution was followed by a severe economic depression in 1784 and 1785. To raise revenue, many states imposed charges on goods from other states. By the mid-1780s, Connecticut was levying heavier duties on goods from Massachusetts than on those from Britain.

The national government was on the verge of bankruptcy. The Dutch and French would lend money only at exorbitant interest rates. A shortage of hard currency made it difficult to conduct commercial transactions. Inflated paper money issued by the individual states was virtually worthless. Many of the new nation’s infant industries were swamped by a flood of British imports.

Economic problems were especially pronounced in the South. Planters lost about 60,000 slaves during the Revolution, including about 25,000 in South Carolina and 5,000 in Georgia. New British trade regulations prohibited the sale of many American agricultural products in the British West Indies, which had been one of the South’s leading markets.

Lacking the protection of the British flag, sailors were seized from American ships by North African corsairs and sold into slavery. In 1785, Algerian pirates boarded an American merchant ship sailing off the coast of Portugal, seized its twenty-one member crew, and enslaved them for twenty-one years. Over the next eight years, a hundred more Americans became captives.

Meanwhile, Britain refused to evacuate its military posts in Detroit, Otswego, New York, and elsewhere in the old Northwest because the states refused to restore loyalist property that had been confiscated during the Revolution. At the same time, Spain refused to recognize American claims to territory between the Ohio River and Florida and in 1784 closed the Mississippi River to American trade. Spanish authorities secretly conspired with Westerners (including the famous frontiersman Daniel Boone) to acquire the area that would become Kentucky and Tennessee.

The Tyranny of the Majority

By the mid-1780s, many of country’s most influential leaders became convinced that state legislatures had become the greatest source of tyranny in America. In the decade after independence, the state legislatures passed more acts than in the previous century. The nation’s leaders were particularly distressed by the kinds of laws the legislatures adopted. These included stay laws (postponing repayment of debts) and paper money bills (allowing debtors to repay debts with worthless paper currency) in violation of the rights of creditors.

Pennsylvania’s government, run by a one-house assembly, was notorious for violating individual rights. It disfranchised and even imprisoned Quakers (who, as pacifists, had refused to fight in the Revolution). The legislature also arbitrarily removed judges.

Several states established special trading relationships with European nations and negotiated treaties with Indian nations.

Many national leaders referred to Rhode Island as “Rogues’ island.” Its delegates blocked nationalist measures—including a five percent duty on imports — in the Confederation Congress, and its legislature made it a criminal offense for merchants to refuse to accept the state’s nearly worthless currency. State judges who struck down the law were removed from office. Nathaniel Gorham of Massachusetts described Rhode Island’s legislature as “a full illustration… of the length to which a public body may carry wickedness and cabal.”

History Happened Here

Shay’s Rebellion

In 1786, nearly 2,000 debtor farmers in western Massachusetts were threatened with foreclosure of their mortgaged property. The state legislature had voted to pay off the state’s Revolutionary War debt in three years; between 1783 and 1786, taxes on land rose more than sixty percent. Desperate farmers demanded a cut in property taxes and adoption of state laws to postpone farm foreclosures. The lower house of the state legislature passed relief measures in 1786, but creditors persuaded the upper house to reject the package.

When lower courts started to seize the property of farmers such as Daniel Shays, a Revolutionary War veteran, western Massachusetts farmers temporarily closed the courts and threatened a federal arsenal. Although the rebels were defeated by the state militia, they were victorious at the polls. A new legislature elected early in 1787 enacted debt relief.

By the spring of 1787, many national leaders believed that the new republic’s survival was at risk. The threat of national bankruptcy, commercial conflicts among the states, Britain’s refusal to evacuate military posts, Spanish intrigues on the western frontier, and armed rebellion in western Massachusetts underscored the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation.

The only solution, many prominent figures were convinced, was to create an effective central government led by a strong chief executive.