A War within A War

Native Americans and the Civil War

In 1861, many Cherokees, Chickasaws, Choctaws, Creeks, and Seminoles decided to join the Confederacy. Some of the tribes’ members owned slaves. In return, the Confederate states agreed to pay all annuities that the U.S. government had provided, and let the tribes send delegates to the Confederate Congress. A Cherokee Chief, Stand Watie, served as a brigadier general for the Confederacy and did not surrender until a month after the war was over.

After the war, these nations were severely punished for supporting the Confederacy. The Seminoles were required to sell their reservation at fifteen cents an acre and to buy new land from the Creeks at fifty cents an acre. Other tribes were required to give up half their territory in Oklahoma. This land would become reservations for the Arapahos, Caddos, Cheyennes, Comanches, Iowas, Kaws, Kickapoos, Pawnees, Potawatomis, Sauk and Foxes, and Shawnees. In addition, each nations had to permit railroads to cut across their land.

A War Within A War

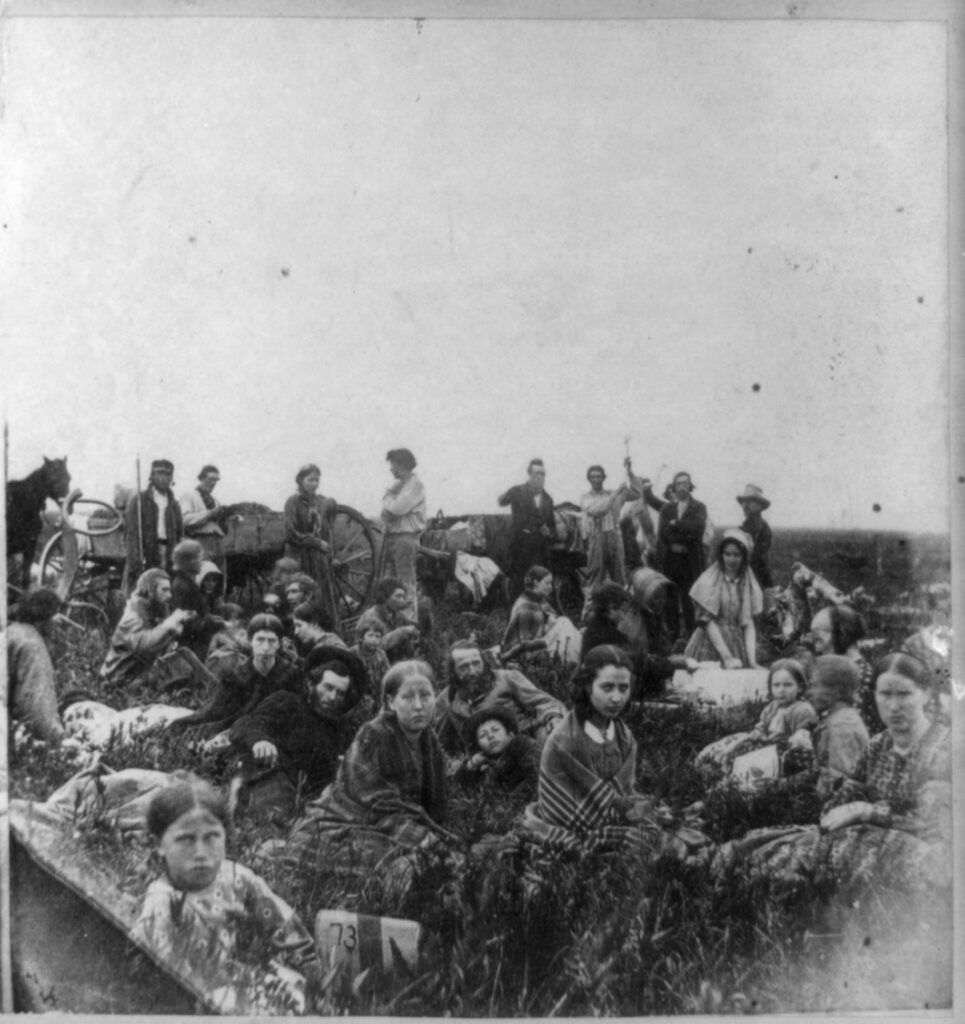

In the midst of the Civil War, a thirty-year conflict began as the federal government sought to concentrate the Plains Indians on reservations. Violence erupted in Minnesota, where, the Santee Sioux were confined to a territory 150 miles long and 10 miles wide by 1862. Denied a yearly payment and agricultural aid promised by treaty, they rose up and killed more than 350 white settlers at New Ulmin in August 1862. Lincoln appointed John Pope, commander of Union forces at the Second Battle of Bull Run, to put down the uprising. Pope promised to deal with the Sioux “as maniacs or wild beasts, and by no means as people with whom treaties or compromises can be made.”

When the Sioux surrendered in September 1862, 1,808 were taken prisoner and 303 were condemned to death. Defying threats from Minnesota’s governor and a senator that warned of the indiscriminate massacre of Indians if all 303 convicted Indians were not executed, Lincoln commuted the sentences of most. But, he did authorize the hanging of 37. This was the largest mass execution in American history, yet Lincoln lost votes in Minnesota for his clemency.

After the discovery of gold in 1864, there was an influx of whites, which spread fighting to Colorado. In November, 1864, a group of Colorado volunteers, under the command of Colonel John M. Chivington, fell on a group of Cheyennes at Sand Creek, where they had gathered under the governor’s protection. “We must kill them big and little,” he told his men. “Nits make lice” (nits are the eggs of lice). The militia slaughtered about 150 Cheyenne, mostly women and children.

History Happened Here

Antietam

The United States achieved independence in part because foreign countries, such as France and Spain, entered the war against Britain on the American side. The Confederacy, too, hoped for foreign aid. In a bold bid to win European support, the Confederacy sought to win a major victory on Northern soil.

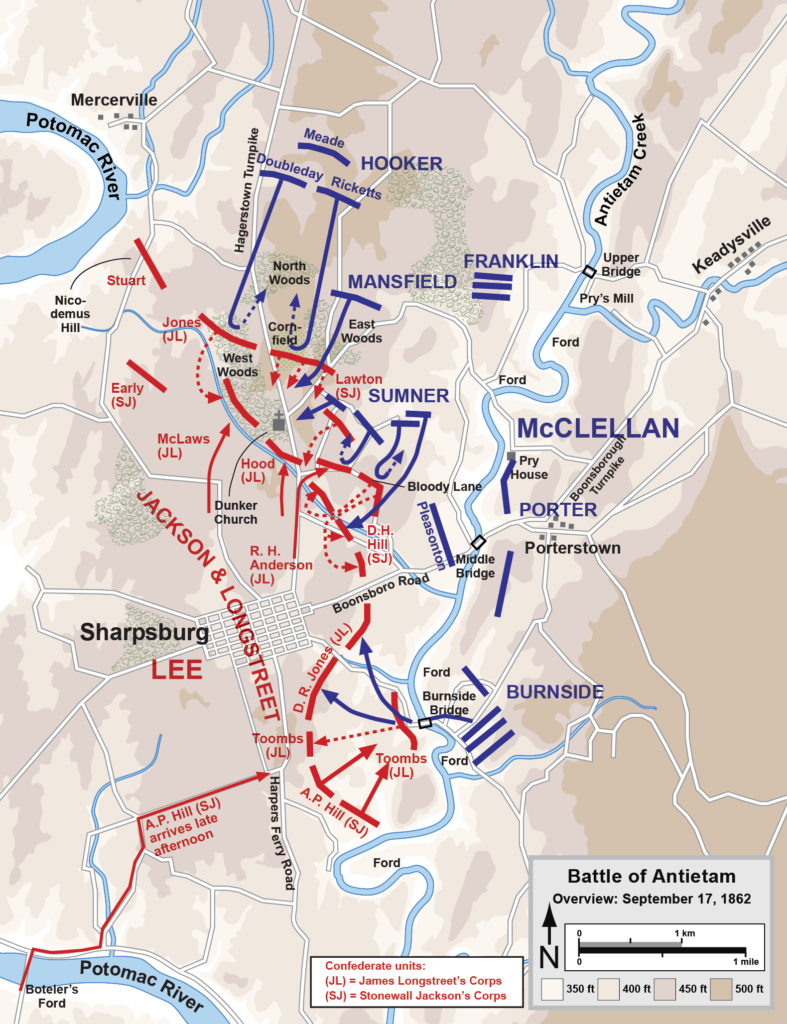

In September 1862, Lee launched a daring offensive into Maryland. No one could be sure exactly what Lee planned to do. In an incredible stroke of luck, a copy of Lee’s battle plan, which had been wrapped around three cigars, fell into the hands of Union General George B. McClellan. After a brief delay on September 17, 1862, McClellan forces attacked Lee at Antietam Creek in Maryland.

The Battle of Antietam, which is sometimes referred to as the Battle of Sharpsburg, produced the bloodiest single day of the Civil War. Lee suffered 11,000 casualties; McClellan, 13,000. Lee was forced to retreat. The North declared the battle a Union victory, but failed to follow up and decisively defeat Lee’s army.

Lincoln mistrusted McClellan, an obsessively cautious general and a Democrat that bitterly opposed the Emancipation Proclamation and called Lincoln a “Gorilla.”

Lincoln was outraged by the statement of one Union officer, Major John J. Key, that the objective of the war was not to crush the Confederate army. Instead, Key implied, the goal was to drag out the war until both sides gave up and the Union could be restored with slavery intact. Key was the only officer to be dismissed from service for uttering disloyal sentiments.

Historical Facts & Fiction

The Significance of Names

During the Civil War, the Union and Confederate armies tended to give battles different names. Thus the battle known to the Union as Bull Run was called Manassas by the Confederacy. Similarly, the Battle of Antietam was known by the Confederacy as the Battle of Sharpsburg. In general, the North tended to name battles and armies after bodies of water, such as the Army of the Potomac or the Army of the Mississippi, while the Confederacy tended to name battles after towns and armies after land areas, such as the Army of Northern Virginia or the Army of Kentucky.

It seems plausible that the Confederacy used such names to convey a sense that its soldiers were defending something of pivotal importance: their homeland.

The Emancipation Proclamation

In July 1862, about two months before President Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, Congress adopted a second Confiscation Act calling for the seizure of the property of slaveholders who were actively engaged in the rebellion. It seems unlikely that this act would have freed any slaves, since the federal government would have to prove that individual slaveholders were traitors. In fact, one of the largest slaveholders in South Carolina was a Baltimore Unionist. Lincoln felt that Congress lacked the legal authority to emancipate slaves. He believed that only the President acting as commander-in-chief had the authority to abolish slavery.

On September 22, 1862, less than a week after the Battle of Antietam, President Lincoln met with his cabinet. As one cabinet member, Samuel P. Chase, recorded in his diary, the President told them that he had “thought a great deal about the relation of this war to Slavery”:

You all remember that, several weeks ago, I read to you an Order I had prepared on this subject, which, since then, my mind has been much occupied with this subject, and I have thought all along that the time for acting on it might very probably come. I think the time has come now. I wish it were a better time. I wish that we were in a better condition. The action of the army against the rebels has not been quite what I should have best liked. But they have been driven out of Maryland, and Pennsylvania is no longer in danger of invasion. When the rebel army was at Frederick, I determined, as soon as it should be driven out of Maryland, to issue a Proclamation of Emancipation such as I thought most likely to be useful. I said nothing to any one; but I made the promise to myself, and (hesitating a little)—to my Maker. The rebel army is now driven out, and I am going to fulfill that promise.

The preliminary Emancipation Proclamation that President Lincoln issued on September 22nd stated that all slaves in designated parts of the South would be freed on January 1, 1863. The President hoped that slave emancipation would undermine the Confederacy from within. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles reported that the President told him that freeing the slaves was “a military necessity, absolutely essential to the preservation of the Union….The slaves [are] undeniably an element of strength to those who [have] their service, and we must decide whether that element should be with us or against us.”

Fear of foreign intervention in the war also influenced Lincoln to consider emancipation. The Confederacy had assumed, mistakenly, that demand for cotton from textile mills would lead Britain to break the Union naval blockade. Nevertheless, there was a real danger of European involvement in the war. By redefining the war as a war against slavery, Lincoln hoped to generate support from European liberals.

Even before Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, Postmaster General Montgomery Blair, a former Democrat from Maryland, warned the President that this decision might stimulate antiwar protests among northern Democrats and cost the administration the 1862 elections.

In fact, Peace Democrats did protest against the proclamation and Lincoln’s assumption of powers not specifically granted by the Constitution. Among his supposed “abuses” were his unilateral decision to call out the militia to suppress the “insurrection,” to impose a blockade of Southern ports, to expand the Army beyond the limits set by law, to spend federal funds without prior congressional authorization, and to suspend the writ of habeas corpus, the right of persons under arrest to have their case heard in court. The Lincoln administration imprisoned about 13,000 people without trial during the war, and shut down Democratic newspapers in New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago for varying amounts of time.

The Democrats failed to gain control of the House of Representatives in the 1862 election, in part because the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation gave a higher moral purpose to the Northern cause.

The Meaning of the Emancipation Proclamation

In October 1862, the London Times dismissed the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation as an empty gesture. “Where he has no power Mr. Lincoln will set the Negroes free,” the newspaper commented; “where he retains power he will consider them as slaves. This is more like a Chinaman beating his two swords together to frighten his enemy than like an earnest man pressing forward his cause.”

In recent years, it has sometimes been charged that the Emancipation Proclamation did not free any slaves, since it applied only to areas that were in a state of rebellion, and explicitly exempted the border states, Tennessee, and portions of Louisiana and Virginia. This view is incorrect. The proclamation did officially and immediately free slaves in South Carolina’s sea islands, Florida, and other locations occupied by Union troops. The Emancipation Proclamation was a crucial first step toward complete emancipation. In effect, it transformed the Union forces into an Army of Liberation.

At the time he issued the preliminary proclamation, Lincoln defended it as a war measure necessary to defeat the Confederacy and preserve the Union. But, it seems clear that Lincoln regarded this argument as a necessary political tactic. When he issued the final proclamation on January 1, 1863, he described it not only as “a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion,” but an “act of justice.”

In July 1863, Hannah Johnson, the daughter of a fugitive slave, heard an erroneous report that Lincoln was going to reverse the Emancipation Proclamation. She wrote the President: “Don’t do it. When you are dead and in Heaven, in a thousand years that action of yours will make the Angels sing your praises….”