Civil War Strategies

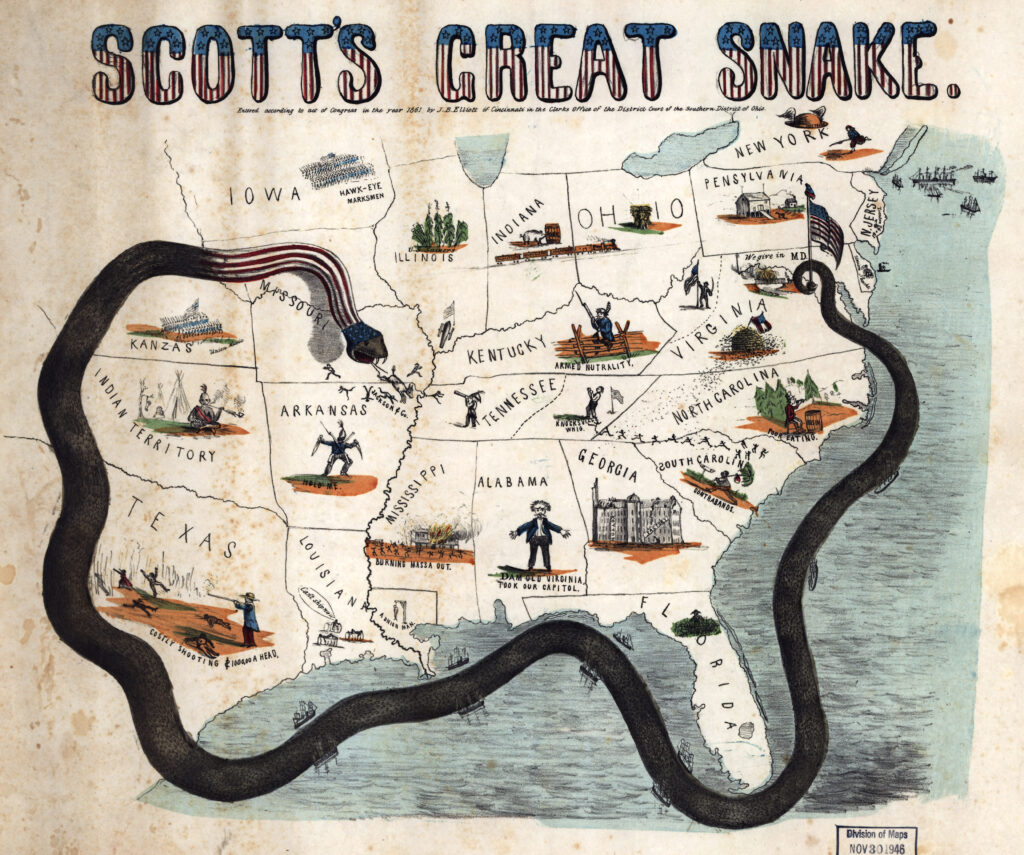

The Anaconda Plan

The initial Union strategy involved blockading Confederate ports to cut off cotton exports and prevent the import of manufactured goods, and using ground and naval forces to divide the Confederacy into three distinct theaters. These were the far western theater, west of the Mississippi River; the western theater, between the Mississippi and the Appalachians; and the eastern theater, in Virginia.

Ridiculed in the press as the “Anaconda Plan,” after the South American snake that crushes its prey to death, this strategy ultimately proved successful. Although about 90 percent of Confederate ships were able to break through the blockade in 1861, this figure was cut to less than 15 percent a year later. Although the Union army suffered repeated defeats and stalemates in the East, victories in the western theater undermined the hopes for Confederate independence.

Pressure of Emancipation

In August 1862, Lincoln stated: “If I could save the Union without freeing any slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.” In fact, by that time, immense pressure was building to end slavery, and Lincoln had privately concluded that he could save the Union only by issuing an emancipation proclamation, which he had already drafted.

The pressure came from a handful of field commanders, Republicans in Congress, abolitionists, and slaves themselves. In May 1861, General Benjamin Butler, a lawyer and politician before the war, declared slaves that escaped to Union lines “contraband of war,” not returnable to their masters. In August, Major General John C. Fremont, commander of Union forces in Missouri, issued an order freeing the slaves of Confederate sympathizers in Missouri. Lincoln, incensed by Fremont’s assumption of authority and fearful that the measure would “alarm our Southern Union friends, and turn them against us,” revoked the order, but allowed Union generals discretion in providing refuge to fugitive slaves.

Congress, too, adopted a series of antislavery measures. In August 1861, it passed a Confiscation Act, authorizing the seizure of all property, including slaves, used for Confederate military purposes. Then in the spring and summer of 1862, Congress abolished slavery in the District of Columbia and the territories, prohibited Union officers from returning fugitive slaves, allowed the President to enlist African Americans in the Army, and called for the seizure of Confederate property.

The border states’ intransigence on the issue of slave emancipation pushed the President in a more active direction. In the spring of 1862, Lincoln persuaded Congress to pass a resolution offering financial compensation to states that abolished slavery voluntarily. Three times, Lincoln met with border state members of Congress to discuss the offer. He even discussed the possibility of emancipation over a 30-year period. In July, however, the Congressmen rejected Lincoln’s offer.

War in the West

Under the Anaconda Plan, Union forces in the West were to seize control of the Mississippi River while Union forces in the East tried to capture the new Confederate capital in Richmond.

In the western theater, the Confederates had built two forts, Fort Donelson along the Cumberland River and Fort Henry on the Tennessee River, which controlled the Kentucky and western Tennessee region and blocked the Union’s path to the Mississippi.

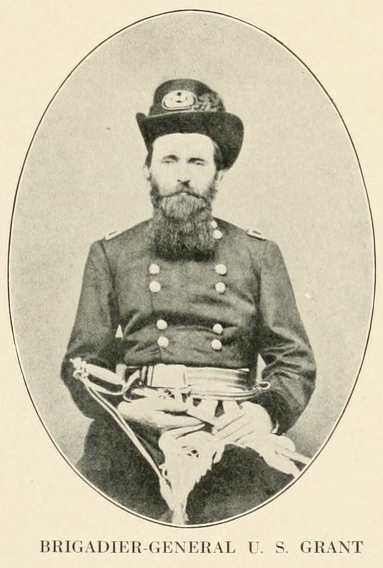

The Union officer responsible for capturing these forts was Ulysses S. Grant, a West Point graduate. Grant had resigned from the Army because of a drinking problem and was working in his father’s tanning shop when the war began. In February 1862, gunboats under Grant’s command took Fort Henry and ten days later, Grant’s men took Fort Donelson, forcing 13,000 Confederates to surrender.

With 42,000 men, Grant proceeded south along the Tennessee River. A Confederate force of 40,000 men, under the command of Beauregard and Johnston tried to surprise Grant before other Union forces could join him at the Battle of Shiloh. After two days of heavy fighting which caused 13,000 Union casualties and over 10,000 Confederate casualties, Grant pushed back the Southern forces. By early June, Union forces controlled the Mississippi River as far south as Memphis, Tennessee.

A Will to Destroy

The Civil War witnessed a will to destroy and a spirit of intolerance that conflicted with Americans’ self-image as a tolerant people committed to compromise. Not only did the conflict see the use of shrapnel and booby traps, it reportedly saw a few Southern women wear necklaces made of Union soldiers’ teeth. In a notorious 1862 order, Union General Ulysses S. Grant expelled all Jews from his military department on the grounds that they were speculating in cotton.

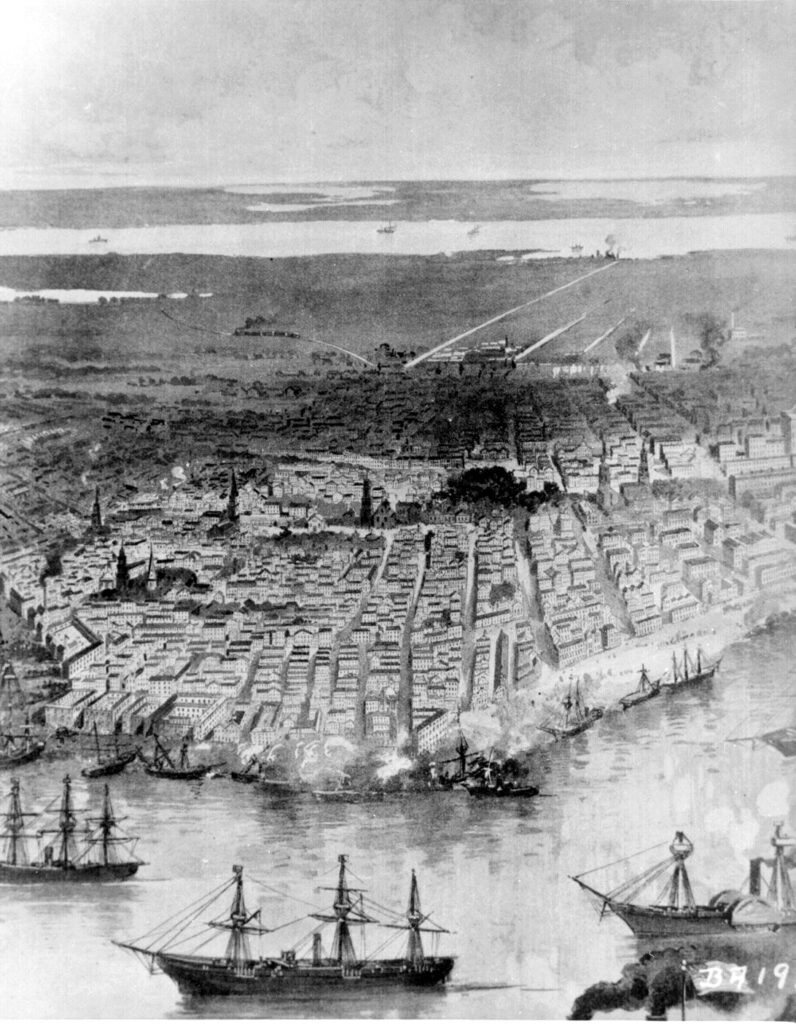

While Grant was driving toward the Mississippi from the North, Northern naval forces under Captain David G. Farragut attacked from the South. In April 1862, Farragut steamed past weak Confederate defenses and captured New Orleans. In New Orleans, Union forces met repeated insults from the city’s women. Major General Benjamin F. Butler ordered that any woman who behaved disrespectfully should be treated as a prostitute. Reaction in the North was mixed. White Southern reaction to “Beast” Butler was predictably harsh.

The Eastern Theater

In the eastern theater, Union General George McClellan’s plan was to land Northern forces on a peninsula between the York and James Rivers southeast of Richmond and then march on the Southern capital. In March 1862, McClelland landed over 100,000 men on the peninsula, only to find his path along the James River blocked by an iron-clad Confederate warship, the Virginia. Nevertheless by May, McClellan’s forces were within six miles of Richmond.

The Confederacy was in desperate straits. The Confederate government had packed up its official records and was prepared to evacuate its capital. It had already lost most of Tennessee, and the Mississippi Valley. It lost New Orleans, its largest city and most important port. Between March and June, Confederate forces suffered serious military defeats in Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, North Carolina, and Tennessee.

In June, however, Robert E. Lee assumed command of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. As a diversionary move to prevent Union forces from concentrating on Richmond, Lee relied on General Thomas J. (“Stonewall”) Jackson to launch lightning-like raids from Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. Then, in a series of encounters between June 26 and July 2, 1862, known as the Seven Days’ Battles, Lee and Jackson forced McClellan, who mistakenly believed he was hopelessly outnumbered, to withdraw back to the James River.

Ironically, it was Robert E. Lee’s battlefield success that would ultimately doom Southern slavery. Had he been a less successful general, it seems imaginable that a compromise settlement might have ended the war without the abolition of slavery.