Why the Civil War Was So Lethal

How Do We Know?

Why the Civil War Was So Lethal?

The Civil War was the deadliest war in American history. Altogether, over 600,000 died in the conflict, more than World War I and World War II combined. A soldier was thirteen times more likely to die in the Civil War than in the Vietnam War.

One reason why the Civil War was so lethal was the introduction of improved weaponry. Cone-shaped bullets replaced musket balls, and beginning in 1862, smooth-bore muskets were replaced with rifles with grooved barrels, which imparted spin on a bullet and allowed a soldier to hit a target a quarter of a mile away. The new weapons had appeared so suddenly that commanders did not immediately realize that they needed to compensate for the increased range and accuracy of rifles.

The Civil War was the first war in which soldiers used repeating rifles, which could fire several shots without reloading, breech-loading arms, which were loaded from behind the barrel instead of through the muzzle, and automated weapons like the Gatling gun. The Civil War also marked the first use by Americans of shrapnel, booby traps, and land mines.

Outdated strategy also contributed to the high number of casualties. Massive frontal assaults and massed formations resulted in large numbers of deaths. In addition, far larger numbers of soldiers were involved in battles than in the past. In the Mexican War, no more than 15,000 soldiers opposed each other in a single battle, but some Civil War battles involved as many as 100,000 soldiers.

Podcast

Responses to Death in the Ninteenth Century

Listen to “Responses to Death in the Ninteenth Century”.

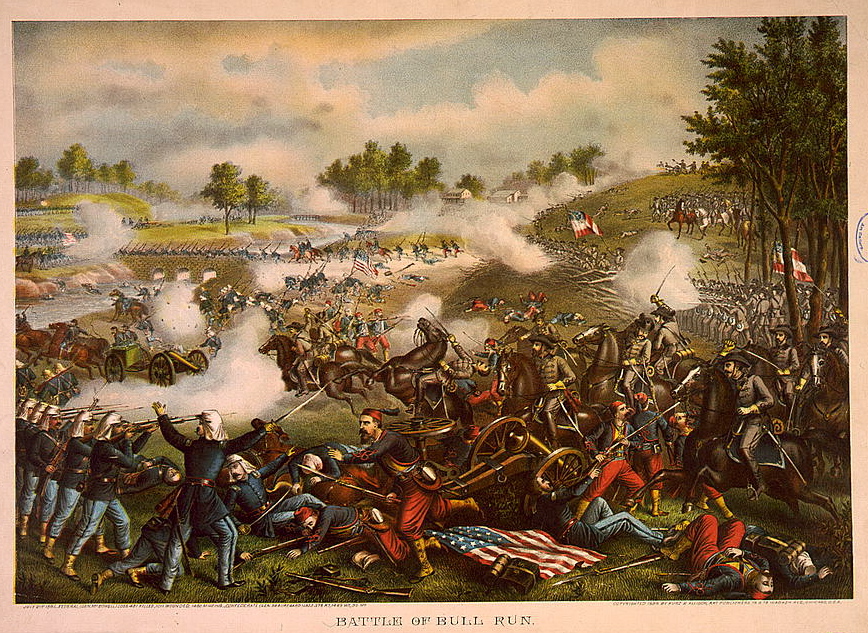

Bull Run

Any hopes for a swift Northern victory in the Civil War were dashed at the First Battle of Bull Run, which was called Manassas by the Confederates. After the surrender of Fort Sumter, two Union armies moved into northern Virginia.

One, led by General Irvin McDowell, had about 35,000 men. The other, with about 18,000 men was led by General Robert Patterson. They were opposed by two Confederate armies, with about 31,000 troops, one led by General Joseph E. Johnston, another led by General Pierre G.T. Beauregard. Both Union and Confederate armies consisted of poorly trained volunteers.

McDowell hoped to destroy Beauregard’s forces while Patterson tied up Johnston’s men. In fact, Johnston’s troops eluded McDowall and joined Beauregard. At Bull Run in northern Virginia 25 miles southwest of Washington, the armies clashed. While residents of Washington ate picnic lunches and looked on, Union troops launched several assaults. When Beauregard counterattacked, Union forces retreated in panic, but Confederate forces failed to take up pursuit.

A War for Union

In July 1861, Congress adopted a resolution by a vote of 117 to 2 in the House and 30 to 5 in the Senate that read: “This war is not waged…for the purpose of overthrowing or interfering with the established institutions of those States, but to maintain the States unimpaired; and that as soon as these objects are accomplished the war should cease.”

Fearful of alienating the slave states that remained in the Union—Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri—or of antagonizing Northerners who would support anti-war Democrats if the conflict were transformed into a war to abolish slavery, Lincoln felt that he had to proceed cautiously. Nevertheless, opponents of slavery regarded the war as a providential opportunity to destroy slavery and the slave power.

John Jay to an unknown recipient. July 24, 1861,

We have an agency at work for the abolition of slavery in the pending war more powerful than all the Conventions we could assemble. Every battle fought will teach our soldiers & the nation at large that slavery is the great cause of the war, that it is slavery which has brutalized & barbarized the South & that slavery must be abolished as our army advances as a military necessity….

I look presently see the entire north…demanding the abolition of slavery not from their Christian regard for the rights of the slave but from motives that partake rather of self-interest—& from a conviction induced only by arguments but by facts that it is slavery alone that has reduced us to our present state.

The continuance of the war, with the unanimous and hearty approval of the whole north…that I would not run the risk of weakening it by an active antislavery movement. Le us polish our tones in patience—for I think I have already seen the beginning of the end.

In its analysis of the Civil War’s causes, The London Times rejected the notion that this was a war about slavery. It argued that the conflict had the same roots as most wars: territorial aggrandizement, political power, and economic supremacy. But few Northerners or Southerners saw the war in such simple terms. To many white Southern soldiers, it was a war to preserve their liberty and their way of life, to prevent abolition and its consequences—race war, racial amalgamation, and, according to one militant Southerner’s words, “the Africanization of the South.” To many Northern soldiers, it was a war to preserve the Union, uphold the Constitution, and defeat a ruthless slave power, which had threatened to subvert republican ideals of liberty and equality.