War Begins

The Secession Crisis

In just three weeks, between January 9, 1861 and February 1, six states of the Deep South joined South Carolina in leaving the Union: Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. Unlike South Carolina, where secessionist sentiment was almost universal, there was significant opposition in the other states. Although an average of 80 percent of the delegates at secession conventions favored immediate secession, the elections at which these delegates were chosen were very close, particularly in Georgia, Alabama, and Louisiana. To be sure, many voters who opposed immediate secession were not unconditional Unionists. But the resistance to immediate secession did suggest that some kind of compromise was still possible.

In the Upper South, opposition to secession was even greater. In Virginia, on February 4, opponents of immediate secession received twice as many votes as proponents, while Tennessee voters rejected a call for a secession convention.

Establishing the Confederacy

In early February 1861, the states of the lower South established a new government, the Confederate States of America, in Montgomery, Alabama, and drafted a constitution. Although modeled on the U.S. Constitution, this document specifically referred to slavery, state sovereignty, and God. It explicitly guaranteed slavery in the states and territories, but prohibited the international slave trade. It also limited the President to a single six-year term, gave the President a line-item veto, required a two-thirds vote of Congress to admit new states, and prohibited protective tariffs and government funding of internal improvements.

As President, the Confederates selected former U.S. Senator and Secretary of War Jefferson Davis (1808-1889). The Alabama secessionist William L. Yancey (1814-1863) introduced Davis as Confederate President by declaring: “The man and the hour have met. Prosperity, honor, and victory await his administration.”

At first glance, Davis seemed much more qualified to be President than Lincoln. Unlike the new Republican President, who had no formal education, Davis was a West Point graduate. And while Lincoln had only two weeks of military experience, as a militia captain, without combat experience in the Black Hawk War, Davis had served as a regimental commander during the Mexican War. In office, however, Davis’s rigid, humorless personality, his poor health, his inability to delegate authority, and, above all, his failure to inspire confidence in his people would make him a far less effective chief executive than Lincoln. During the war, a Southern critic described Davis as “false and hypocritical…miserable, stupid, one-eyed, dyspeptic, arrogant…cold, haughty, peevish, narrow-minded, pig-headed, [and] malignant.”

Following secession, the Confederate states attempted to seize federal property within their boundaries, including forts, customs houses, and arsenals. Several forts, however, remained within Union hands, including Fort Pickens in Pensacola, Florida, and Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina’s harbor.

Last Ditch Efforts at Compromise

Threats of secession were nothing new. Some Southerners had threatened to leave the Union during a Congressional debate over slavery in 1790, the Missouri Crisis of 1819 and 1820, the Nullification Crisis of 1831 and 1832, and the crisis over California statehood in 1850. In each case, the crisis was resolved by compromise. Many expected the same pattern to prevail in 1861.

Four months separated Lincoln’s election to the presidency and his inauguration. During this period, there were two major compromise efforts. John J. Crittenden (1787-1863) of Kentucky, who held Henry Clay’s old Senate seat, proposed a series of Constitutional amendments, including one to extend the Missouri Compromise line to the Pacific Ocean, in defiance of the Compromise of 1850 and the Dred Scott decision. The amendment would prohibit slavery north of the line but explicitly protect it south of the line. On January 16, 1861, however, the Senate, which was controlled by Democrats, refused to consider the Crittenden compromise. Every Republican Senator opposed the measure and six Democrats abstained. On March 4, the Senate reconsidered Crittenden’s compromise proposal and defeated it by a single vote.

Meanwhile, Virginia had proposed a peace convention to be held in Washington, D.C., February 4, 1861, the very day that the new Confederate government was to be set up in Alabama. Delegates, who represented 21 of the 34 states, voted narrowly to recommend extending the Missouri Compromise line to the Pacific. The delegates also would have required a four-fifths vote of the Senate to acquire new territory. The Senate rejected the convention’s proposals 28 to 7.

Compromise failed in early 1861 because it would have required the Republican Party to repudiate its guiding principle: no extension of slavery into the western territories. President-elect Lincoln made the point bluntly in a message to a Republican in Congress: “Entertain no proposition for a compromise in regard to the extension of slavery. The instant you do, they have us under again; all our labor is lost, and sooner or later must be done over….The tug has to come and better now than later.”

With compromise unattainable, attention shifted to the federal installations located within the Confederate states, especially to a fort located in the channel leading to Charleston Harbor. In November 1860, the U.S. government sent Colonel Robert A. Anderson (1805-1871), a pro-slavery Kentuckian and an 1825 West Point graduate, to Charleston to command federal installations there. On December 26, under cover of darkness, he moved his forces (10 officers, 76 enlisted men, 45 women and children, and a number of laborers) from the barely defensible Fort Moultrie to the unfinished Fort Sumter. On January 9, 1861, President James Buchanan made an effort to reinforce the garrison, but the supply ship was fired on and driven off.

Texas Secession

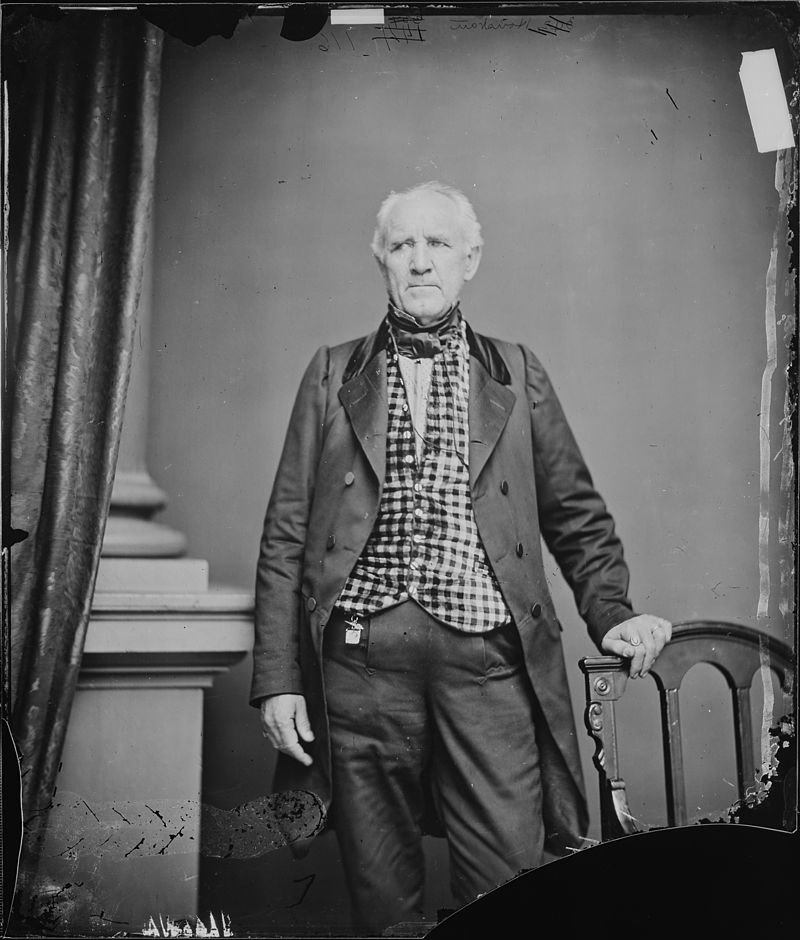

On February 1, a secession convention in Texas voted to leave the Union. Three weeks later, a popular vote ratified the decision by a three-to-one margin. Texas Governor, Sam Houston (1793-1863), who owned a dozen slaves, repudiated secession and refused to take an oath of allegiance to the Confederacy. As a result, he was forced from office. Houston predicted: “Our people are going to war to perpetuate slavery, and the first gun fired in the war will be the [death] knell of slavery.”

New York Herald (January 14, 1861) From: Texas: Our Galveston Correspondent

I do not know that I can find language sufficiently strong to express to you the unanimity and intensity of the feeling in this region in opposition to the perpetuation of the Union under the rule of President Lincoln and a black republican administration. That there are among us men of a conservative tendency, and hopeful preservation of the rights and honor of the Southern States in the confederation, is true, and also a class upon whom the present depression of all material interests acts more powerfully than considerations of future political or social stability. But these are few, very few, in number, while the great majority are for secession without compromise on any terms.

As in the rest of the Gulf States that I have visited, the desire for revolution is paramount among the people, and the Union is constantly spoken of as both a danger and a disgrace that is to be averted and avoided. The benefits that it has conferred upon all sections of the country are never referred to, and seem to be entirely forgotten; and the fact that a revulsion of public sentiment may have occurred in the North, equal to that which has taken place in the South since the Presidential election, never seems to be for a moment considered possible. The popular majority which all the free States have exhibited for Lincoln is looked upon as irreversible, and the party slogan that slavery is “an evil and a crime,” and must be belted in which a line of socially hostile States, is accepted as the permanent opinion of the Northern people. It is not alone the fear of danger to their social organization that rouses the Southern community to resistance and revolution; the moral obloquy that is conveyed in the sweeping condemnation of an institution which, in a community of mixed races, is considered to be the most wise, and consequently the most productive of high moral results, touches the honor of every Southern man and woman, and leads to that blind resentment which discards all considerations of material interest. The coming administration of Lincoln is looked upon as the embodiment of this moral slur upon Southern society and hence it is believed that submission to it will be an admission of inferiority in the face of the whole world.

This sentiment has swept away all the old part distinctions in the South, and made revolutionists of Breckinridge men and Bell men alike to such a degree that formerly recognized part leaders are now partyless and powerless, and the masses have shown themselves to be far in advance of those to whom they have hitherto been accustomed to look for counsel in public affairs. So ripe is the feeling for revolution here, that is today attacking the State government, as well as the general government. Governor [Sam] Houston had refused to assemble the State Legislature for the purpose of considering the present political crisis, and had assigned valid reasons of State policy for his course. These were generally admitted to be binding upon him; and yet the people we determined to assemble in convention and take revolutionary action, in which the State government must have acquiesced or be superseded. In consequence of this state of things Governor Houston has changed his course, and issued his proclamation for the assembly of the Legislature.

The new popular divisions for the election of delegates to this convention are what may be termed cooperation secessionists, who desire that hte State shall go into a new Southern confederacy; and Lone Star men, who oppose any future political union with other States. The agitation and discussion of these principles of party organization have just begun, and Lone Star organizations are being formed. It is stated in some quarters that the Lone Star men are in favor of exhausting every measure for obtaining guarantees for Southern institutions in the Union before resorting to secession, and it is probable that the coming political conflict in this State will take the shape of a struggle to remain in the confederation with new constitutional guarantees for the South, or a return to the old condition of the independent republic of Texas.

Such a course opens grand visions of achievement and glory to all young minds. It is believed that Arizona will unite with us and give us a Pacific as well as an Atlantic shore. In the present dilapidated condition of Mexico, large accessions from her territory to the new republic are deemed possible. Tamanlipas, Nuevo Leon, Coahuila, Chihuahua and Sonora offer a vast field for enterprise and the carrying out of numerous fortunes in their fertile lands and prolific mineral resources, and thousands upon thousands of energetic and ambitious youth would leave the disintegrated States of a disrupted confederacy and seek a new future under the Lone Star of Texas. How long it will be before these anticipations are realized will depend upon the representatives in Congress of the Northern States, if they persist in their hostility to the present necessary social organization of the South, nothing can preserve the present Union. None of the extreme Southern States will remain in the confederacy except upon the admitted equality of Southern to Northern society, and the recognized wisdom of domestic servitude for the inferior race where whites and blacks are living in community.

Herein lies the great doubt of the Southern people. They see the feeling of hostility to African slavery pervading the churches, the Sunday schools, the moral propagandist societies, the school books, and every kind of moral and religious organization in the North, and they believe that the Northern people are so indoctrinated with hatred to an institution which they know theoretically only, through the most exaggerated and highly colored representations of those evils that are to be found in every constituted society, that they despair of justice being rendered to them. Hence the prevailing wish to sever the bonds of political union. The anti-slavery oligarchy, which rules the North through the clergy and the demagogues, are believed to be immutably enthroned there, whether their policy be for weal or woe to the country. It is for the Northern people to disabuse this belief, and only by so doing can the Union and its immense benefits be preserved to us.

War Begins

Lincoln was convinced that the Confederate states had seceded from the Union for the sole purpose of maintaining slavery. Like President Jackson before him, he considered the Union to be permanent, an agreement by the people and not just of the states. Further, he strongly agreed with the sentiments voiced by Daniel Webster, when that Whig Senator declared in 1830, “Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable.” Lincoln, too, believed that a strong Union provided the only firm safeguard for American liberties and republican institutions.

In his inaugural address, Lincoln attempted to be both firm and conciliatory. He declared secession to be wrong; but he also promised that he would “not interfere with the institution of slavery where it exists.” He announced that he would use “the power confided to me…to hold, occupy, and possess the property and places belonging to the Government.” But he assured Southerners that “there would be no invasion, no using of force against or among the people anywhere.”

When he delivered his inaugural address, the new President assumed that there was time for Southern pro-union sentiment, which he greatly overestimated, to reassert itself, making a peaceful resolution to the crisis possible. The next morning, however, he received a letter from Robert Anderson informing him that Fort Sumter’s supplies would be exhausted in four to six weeks and that it would take a 20,000-man force to reinforce the fort.

Crisis at Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina’s harbor had become a key symbol of whether the Confederate states exercised sovereignty over their territory.

Lincoln received conflicting advice about what to do. Winfield Scott, his commanding general, saw “no alternative to surrender,” convinced that it would take eight months to prepare naval and ground forces to relieve Fort Sumter. Secretary of State William H. Seward also favored abandoning the fort to avoid provoking a civil war, but also considered the possibility of inciting a foreign war (probably with France or Spain) as a way to reunite the country. Lincoln’s Postmaster General Montgomery Blair and Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase favored dispatching a force of warships and transports to relieve the fort and assert federal authority, since “every hour of acquiescence … strengthens [the rebels’] hands at home and their claims to recognition as an independent people abroad.”

In the end, Lincoln decided to try to peacefully re-supply the fort with provisions and to inform the Confederate government of his decision beforehand. Unarmed ships with supplies would try to relieve the fort. Only if the South Carolinians used force to stop the mission would warships, positioned outside Charleston Harbor, go into action. In this way, Lincoln hoped to make the Confederacy responsible for starting a war.

Upon learning of Lincoln’s plan, Jefferson Davis ordered General Pierre G.T. Beauregard (1818-1893) to force Fort Sumter’s surrender before the supply mission could arrive. At 4:30 a.m. April 12, Confederate guns began firing on Fort Sumter. Thirty-three hours later, the installation surrendered. Incredibly, there were no fatalities on their side.

Ironically, the only fatalities at Fort Sumter occurred just after the battle ended. During the surrender ceremony, a pile of cartridges ignited, killing one soldier, fatally wounding another, and injuring four.

Lincoln responded to the attack on Fort Sumter by calling on the states to provide 75,000 militiamen for 90 days service. Twice that number volunteered. But the eight slave states still in the Union refused to furnish troops, and four–Arkansas, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia–seceded.

One individual who felt especially torn by the decision to support the Union or join the Confederacy was Robert E. Lee (1807-1870) of Virginia. Lee was Winfield Scott’s choice to serve as field commander of the Union army, but when a state convention voted to secede, he resigned from the U.S. army, announcing to his sister that he could not “raise my hand against my birthplace, my home, my children. Save in defense of my native state, I hope I may never be called on to draw my sword.” After joining the Confederate army, he predicted “that the country will have to pass through a terrible ordeal, a necessary expiation perhaps for national sins.”

Prospects of Victory

Many Northerners felt confident of a quick victory. In 1861, the Union states had 22.5 million people, compared to just 9 million in the Confederate states (including 3.7 million slaves). Not only did the Union have more manpower, it also had a larger navy, a more developed railroad system, and a stronger manufacturing base. The North had 1.3 million industrial workers, compared to the South’s 110,000. Northern factories manufactured nine times as many industrial goods as the South, seventeen times as many cotton and woolen goods, thirty times as many boots and shoes, twenty times as much pig iron, twenty-four times as many railroad locomotives, and 33 times as many firearms.

The Confederates also felt confident. For one thing, the Confederacy had only to wage a defensive war and wait for northern morale to erode. In contrast, the Union had to conquer and control the Confederacy’s 750,000 square miles of territory. Further, the Confederate army seemed superior to that of the Union. More Southerners had attended West Point or other military academies, had served as army officers, and had experience using firearms and horses. At the beginning of 1861, the U.S. Army consisted of only 16,000 men, most of whom served on the frontier fighting Indians. History, too, seemed to be on the South’s side. Before the Civil War, most nations that had fought for independence, including, of course, the United States, had won their struggle. A school textbook epitomized southern confidence: “If one Confederate soldier can whip seven Yankees,” it asked, “how many soldiers can whip 49 Yanks?”