How Revolutionary Was the Revolution?

The African American Dilemma

During the Revolution, African Americans faced a wrenching decision about which side to support.

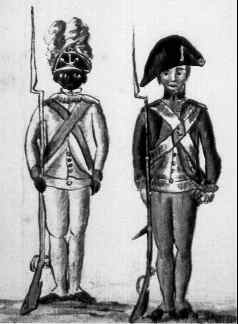

At least 5,000 blacks fought in the Revolution, including in the Battles of Lexington, Concord, Bunker Hill, and Yorktown. Blacks served the Patriot cause as infantrymen, artillerymen, scouts, couriers, and spies. While many white soldiers served just three to nine months, the average African American soldier served four-and-a-half years.

At the same time, a significant number of African Americans fought on the British side. One of the most famous black Loyalist soldiers was known as Colonel Tye. A fugitive slave born in Monmouth County, New Jersey, Tye commanded as many as eight hundred men and staged guerrilla war against the American patriots in Staten Island and New Jersey in 1778 and 1779 before he died of an infection after being shot.

During the Revolution, tens of thousands of blacks fled slavery, escaping behind British lines. These included a quarter of the slaves in South Carolina and a third of those in Georgia.

Many fugitive slaves found refuge in New York during the city’s British occupation. At the end of the Revolution, some 3,000 black Loyalists were evacuated from New York to Nova Scotia. Eventually, many of these people left to settle Freetown in Sierra Leone on Africa’s West coast.

Thinking Comparatively

How Revolutionary Was the Revolution?

Richard Price, a British Unitarian minister, called the American Revolution the most important event in the history of the world since the birth of Christ. At first glance, this seems like a gross overstatement.

The American Revolution was not a great social revolution like the ones that occurred in France in 1789 or in Russia in 1917 or in China in 1949. A true social revolution destroys the institutional foundations of the old order and transfers power from a ruling elite to new social groups.

Nevertheless, the Revolution had momentous consequences. It created the United States. It transformed a monarchical society, in which the colonists were subjects of the Crown, into a republic, in which they were citizens and participants in the political process. The Revolution also gave a new political significance to the middling elements of society—artisans, merchants, farmers, and traders—and made it impossible for elites to openly disparage ordinary people.

During the colonial era, the percentage of white men who voted or participated in politics was low. There were no organized political parties, and adult white men tended to defer to gentlemen. Established merchants, wealthy lawyers, and large planters held the major political offices. But in the years leading up to the Revolution, popular participation in politics increased. Voter turnout climbed as did the number of contested elections. Political pamphleteering also became more common. By the time the Revolution was over, ordinary people had become much more heavily involved in the political process.

The Revolution also profoundly altered social expectations. It led to demands that the vote be extended to a larger proportion of the population and that public offices be elected by the people. During and after the Revolution, smaller farmers, artisans, and laborers began increasingly to participate in state legislative elections, and men claiming to represent their interests began to win office and wield power. Leaders in the new state governments were less wealthy, more mobile, and less likely to be connected by marriage and kinship than those before the Revolution. For the first time, state assemblies erected galleries to allow the public to watch legislative debates.

Above all, the Revolution popularized certain radical ideals—especially a commitment to liberty, equality, government of the people, and rule of law. However compromised in practice, these egalitarian ideals inspired a spirit of reform. Slavery, the subordination of women, and religious intolerance—all became problems in a way that they had never been before.

The Revolution also set into motion larger changes in American life. It inspired Americans to try to reconstruct their society in line with republican principles. The Revolution inspired many Americans to question slavery and other forms of dependence, such as indentured servitude and apprenticeship. By the early nineteenth century, the Northern states had either abolished slavery or adopted gradual emancipation plans. Meanwhile, white indentured servitude had virtually disappeared, and thousands of African Americans succeeded in escaping from slavery.

The Revolution was accompanied by dramatic changes in the lives of women. Before the Revolution, many women were involved in campaigns to boycott British imports. During the conflict, many women made items for the war effort and ran farms and businesses in the absence of their husbands. After the Revolution, American women, for the first time, protested against male power and demanded greater respect inside and outside the home.

What if…

Slave Unrest

The Revolution’s success was not preordained. If France had not entered the conflict in 1778 (followed by Spain in 1779 and the Netherlands in 1780)—and threatened British possessions in Canada, Gibraltar, and the West Indies—the Revolution might have failed.

One potential factor that might have shaped the Revolution’s outcome was slavery.

Both the British and the Patriots recognized that slavery might play a pivotally important role in the outcome of the Revolution. Lord Dunmore, the royal governor of Virginia, promised liberty to slaves who joined British forces and later John and Henry Laurens urged the Continental Congress to recruit an army of three thousand slave troops. Although some 5,000 African Americans served in the American army during the Revolution, there were few efforts to foment slave unrest as a way to win the Revolution.

History Through…

…Primary Sources:

In our daily lives, Americans tend to give little thought to the importance of ideas. In fact, ideas—often simplified and misunderstood—have immense power. They can even change the course of history. At various times in the past, ideas have arisen that grip the popular imagination.

That was very much the case with the Revolution and ideals of liberty, equality, and popular self-government that it spread. The Revolution would inspire many groups of peoples—including enslaved African Americans and women—to demand greater rights.

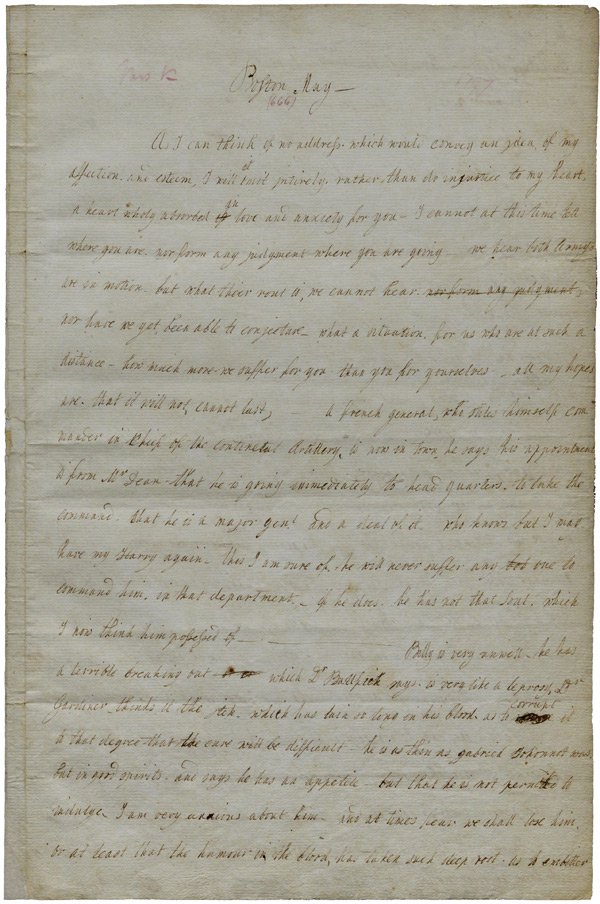

Wartime conditions thrust new responsibilities upon American women. With many husbands absent, women assumed heightened responsibilities from managing family finances to operating family farms and shops. The correspondence between Lucy Knox and her husband Henry, one of Washington’s leading generals, an artillery expert, and his future Secretary of War, underscores the disruptive effects of the Revolution on women’s lives.

Henry Knox (1750-1806) was only twenty-seven at the time of this letter, and he and his wife had been married only three years. Her family, the Fluckers, were Loyalists who had fled Boston. This is the lost father, mother, brother, and sisters she refers to in her letter, illustrating the way that the Revolution divided families.

History Through…

…Primary Sources: “I Hope You Will Not Consider Yourself as Commander in Chief of Your Own House”

Lucy Knox to her husband, General Henry Knox, August 23, 1777

My dearest friend,

I wrote you a line by the last post just to let you know I was alive, which…was all I could then say with propriety for I had serious thoughts that I never should see you again, so much was I reduced by only four days of illness but by help of a good constitution I am surprisingly better today. I am now to answer your three last letters in one of which you ask for a history of my life. It is my love barren of adventure and replete with repetition that I fear it will afford you little amusement. How such as it is I give to you. In the first place, I rise about eight in the morning so late an hour you will say but the day after that is full long for a person in my condition. I presently after sit down to my breakfast, where a page in my book and a dish of team, employ me alternately for about an hour. When after seeing that family matters go on right, I repair to my work…for the rest of the forenoon. At two o’clock I usually take my solitary dinner where I reflect upon my past happiness. I used to sit at the window watching for my Harry, and when I saw him coming my heart would leap for joy when he was at my own and never happy from me when the bare thought of six months absence would have shook him. To divert Alex’s pleas I place my little Lucy by me at table, but the more engaging her little actions are so much the more do I regret the absence of her father who would take such delight in them. In the afternoon I commonly take my chaise and ride into the country or go to drink tea with one of my few friends…. then with any…I often spend the evening, but when I return home how that describe my feelings to find myself entirely alone, to reflect that the only friend I have in the world is such an immense distance from me to think that the may be sick and I cannot assist him. My poor heart is ready to burst, you who know what a trifle would make me unhappy can conceive what I suffer now. When I seriously reflect that I have lost my father, mother, brother, and sisters entirely lost them I am half distracted…. I have not seen him for almost six months, and he writes me without pointing at any method by which I may ever expect to see him again. Tis hard my Harry indeed it is I love you with the tenderest the purest affection. I would undergo any hardship to be near you and you will not let me….

The very little gold we have must be reserved for my love in case he should be taken [for ransom]….

[A person] if he understands business he might without capital make a fortune–people here without advancing a shilling frequently clear hundreds in a day, such chaps as Eben Oliver are all men of fortune while persons who have ever lived in affluence are in danger of want and that you had less of the military man about you, you might then after the war have lived at ease all the days of your life, but now, I don’t know what you will do, you being long accustomed to command–will make you too haughty for mercantile matters–tho I hope you will not consider yourself as commander in chief of your own house, but be convinced that there is such a thing as equal command.