Declaring Independence

Declaring Independence

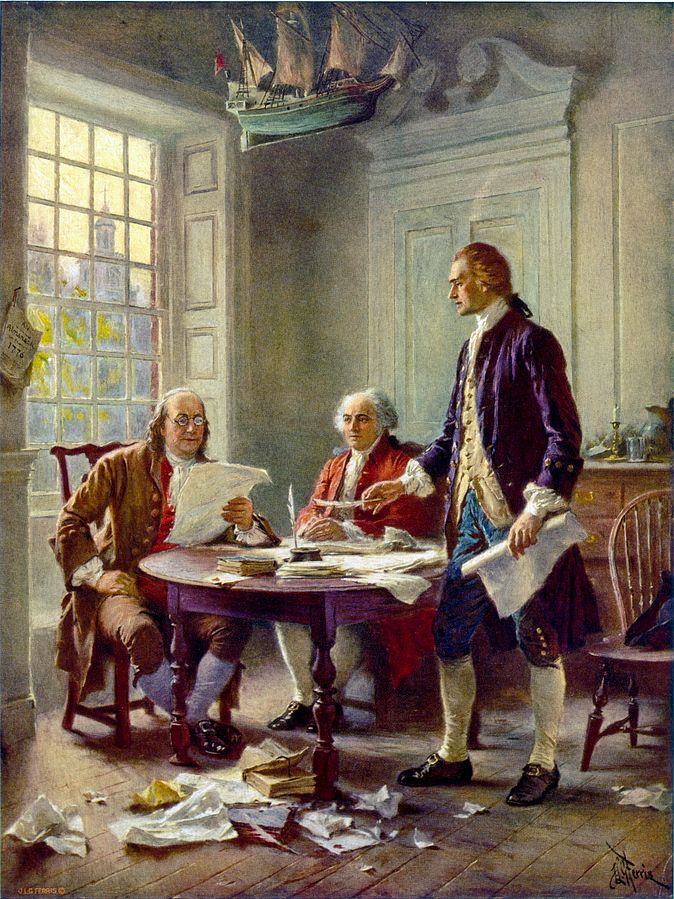

On June 7, 1776—fourteen months after the battles of Lexington and Concord—Richard Henry Lee of Virginia introduced a resolution to the Second Continental Congress “that these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States…” After several days of debate, Congress appointed a committee to draft a declaration of independence. The committee asked Thomas Jefferson to write the first draft, which he completed in just two days.

On July 2, Congress unanimously approved Lee’s resolution. The delegates then went over Jefferson’s draft line-by-line, refining the wording and eliminating a clause that blamed King George III for encouraging the slave trade. On July 4, Congress formally adopted the Declaration of Independence, explaining “to a candid world” why the United States had declared their freedom from Britain.

As the delegates signed the Declaration, they feared for their lives. “I shall have a great advantage over you when we are all hung for what we are doing,” said Benjamin Harrison of Virginia to Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts. “From the size and weight of my body I shall die in a few minutes, but from the lightness of your body you will dance in the air for an hour or two before you are dead.”

History as it Happened

Why Is the Declaration Significant?

Between April and early July 1776, there were ninety declarations of independence by provincial congresses in nine colonies, as well as by Maryland counties, by Massachusetts town meetings, by New York and Philadelphia artisans, by militia members, by South Carolina grand jurors, and by Virginia county leaders.

It might seem, then, that the Declaration of Independence was unnecessary. But in fact, the Declaration is of crucial importance. It is the defining statement of the fundamental principles of American democracy. One tenet is that governments exist to protect the rights of the people and that they have a right to overthrow an unjust or tyrannical government. A second tenet is that all people are equal in their right to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Lessons of History

War as a Central Element in American History

War has always been central to American history. During the colonial era, more than half the period witnessed warfare—against Native Americans, the Spanish, and the French. Today, defense remains the nation’s top budget priority. nearly $600 billion, which is over half of the federal government’s discretionary spending. The Department of Defense, the world’s largest employer, has more than 1.3 million men and women on active duty, and 742,000 civilian personnel. Currently, the United States has more than eight hundred military bases in some eighty countries.

Apart from the immense human toll—more than 1.3 million Americans killed in war and the 1.5 million wounded—war is history’s lynchpin and pivot point: Wars constitute any of history’s essential turning points with far-reaching implications for the future.

History Through…

…Primary Sources: Was the Revolution Justified?

Did the colonists have grievances against the British government substantial enough to justify revolution? In the Declaration of Independence, the American patriots listed “a history of injuries and usurpations” designed to establish “an absolute Tyranny over these states.” What specific abuses did the delegates cite?

1. “He has refused his assent to laws necessary for the public good.”

The King had rejected laws passed by colonial assemblies.

2. “He has forbidden his governors to pass laws of pressing importance.”

Royal governors had rejected any colonial laws that did not have a clause suspending their operation until the King approved them.

3. “He has refused to pass laws unless people would relinquish the right of representation.”

The Crown had failed to redraw the boundaries of legislative districts to ensure that newly settled areas were fairly represented in colonial assemblies.

4. “He has called together legislative bodies at places distant from the depository of their public records.”

Royal governors sometimes had forced colonial legislatures to meet in inconvenient places.

5. “He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly.”

Royal governors had dissolved colonial legislatures for disobeying their orders or protesting royal policies.

6. “He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected.”

Royal governors had delayed in calling for elections of new colonial assemblies.

7. “He has endeavored to prevent the population of these States.”

The King had impeded the development of the colonies by prohibiting the naturalization of foreigners (in 1773) and raising the purchase price of western lands (in 1774).

8. “He has obstructed the administration of justice.”

The King had rejected a North Carolina law setting up a court system.

9. “He has made judges dependent on his will alone.”

The Crown had insisted that judges serve at the King’s pleasure and that they should be paid by him.

10. “He has erected a multitude of new offices to harass our people.”

The royal government had appointed tax commissioners and other officials.

11. “He has kept among us, in times of peace, standing armies.”

The Crown had kept an army in the colonies after the Seven Years’ War without the consent of the colonial legislatures.

12. “He has affected to render the military independent of civil power.”

The British government had named General Thomas Gage, commander of British forces in America.

13. “He has subject[ed] us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution.”

The Royal government had claimed the power (in the Declaratory Act of 1766) to make all laws for the colonies.

14. “For quartering armed troops among us.”

The Crown had required the colonies to house British troops stationed in America.

15. “For protecting them from punishment for murders.”

Parliament had passed a 1774 law permitting British soldiers and officials accused of murder while in Massachusetts to be tried in Britain.

16. “For cutting off our trade.”

Parliament had enacted laws restricting the colonies’ right to trade with foreign nations.

17. “For imposing taxes on us without our consent.”

Parliament had imposed taxes (such as the Sugar Act of 1764) without the colonists’ consent.

18. “For depriving us of the benefits of trial by jury.”

The royal government had deprived colonists of a right to a jury trial in cases dealing with smuggling and other violations of trade laws.

19. “For transporting us beyond seas to be tried.”

A 1769 Parliamentary resolution declared that colonists accused of treason could be tried in Britain.

20. “For abolishing the free system of English laws in a neighboring province.”

The 1774 Quebec Act extended Quebec’s boundaries to the Ohio River and applied French law to the region.

21. “For taking away our charters.”

Parliament (in 1774) had restricted town meetings in Massachusetts, had decided that the colony’s councilors would no longer be elected but would be appointed by the king, and had given the royal governor control of lower court judges.

22. “For suspending our legislatures.”

Parliament (in 1767) had suspended the New York Assembly for failing to obey the Quartering Act of 1765.

23. “Waging war against us.”

The Crown had authorized General Thomas Gage to use force to make the colonists obey the laws of Parliament.

24. “He has plundered our seas…burnt our towns.”

The British government had seized American ships that violated restrictions on foreign trade and had bombarded Falmouth (now Portland), Maine; Bristol, Rhode Island; and Norfolk, Virginia.

25. “He is…transporting large armies of foreign mercenaries.”

The British army hired German mercenaries to fight the colonists.

26. “He has constrained our fellow citizens to bear arms against their country.”

The Crown had forced American sailors (under the Restraining Act of 1775) to serve in the British navy.

27. “He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us.”

In November 1775, Virginia’s royal governor had promised freedom to slaves who joined British forces. The royal government also instigated Indian attacks on frontier settlements.

Parliament seemed intent on slowing the colonies’ growth and protecting British economic interests at the colonists’ expense. Royal officials had restricted westward expansion, levied taxes without the colonists’ consent, and stationed a standing army in the colonies in peacetime. In addition, the Crown had expanded the imperial bureaucracy, made the West a preserve for French Catholics and Indians, and infringed on traditional English liberties, including the right to trial by jury, freedom from arbitrary arrest and trial, freedom of speech and conscience, and the right to freely trade and travel. Parliament had also restricted meetings of legislative assemblies, vetoed laws passed by assemblies, billeted soldiers in private homes, and made royal officials independent of colonial legislatures.

Primary Sources

The American Revolution was not simply the result of British political missteps, it was also a product of the way that colonists interpreted British actions. When Britain began to tax Americans, to regulate their trade, to station troops in their midst, and to deny colonists the right to expand westward, many colonists viewed these events through an ideological prism that had been shaped by English thinkers who had warned about the dangers posed by a standing army, the evils of public debt, and government officials lusting after power.

During the 1760s and 1770s many colonists began to conceive of America as a truly “republican” society—one that emphasized personal independence, public virtue, and a suspicion of concentrated power as essential ingredients of a free society. They conceived of America as a society inhabited by people who governed themselves and enjoyed personal rights and liberties. A growing number of colonists contrasted their society with Britain’s political corruption and bloated governmental bureaucracy.

John Adams commented that “The Revolution was affected before the war commenced. The Revolution was in the hearts and minds of the people…This radical change in the principles, opinions, and sentiments of the people was the real American Revolution.”

Perhaps, the most important cause of the Revolution lay in the way that the colonists perceived and interpreted events. In the years before the Revolution, the colonists embraced an ideology which held that liberty was fragile and threatened by the conspiratorial designs of scheming politicians. This ideology led colonists to interpret British policies as part of a deliberate scheme to impose tyrannical oppression in America and reduce the colonists to slavery.

History Through…

…Primary Sources: “Calculated for Enslaving These Colonies

Read the following letter to the King of England.

Petition from the General Congress in America to the King, October 26, 1774

Most Gracious Sovereign,

We your majesty’s faithful subjects…[beg]to lay our grievances before the throne.

A standing army has been kept in these colonies ever since the conclusion of the late war, without the consent of our assemblies; and this army, with a considerable naval armament, has been employed to enforce the collection of taxes;

The authority of the commander in chief, and, under him, of the brigadier general, has in time of peace been rendered supreme in all the civil governments in America.

The commander in chief of your majesty’s forces in North-America has in time of peace been appointed governor of a colony.

The charges of usual officers have been greatly increased, and new, expensive, and oppressive officers have been multiplied.

The judges of the admiralty and vice-admiralty courts are empowered to receive their salaries and fees from the effects condemned by themselves. The officers of the customs are employed to break open and enter houses without the authority of any civil magistrate, founded on legal information.

The judges of courts of common law have been made entirely dependent on one part of the legislature for their salaries, as well as for the duration of their commissions….

Commerce has been burthened with many useless and oppressive restrictions….

In the last session of parliament, an act was passed for blocking up the harbour of Boston; another empowering the governor of Massachusetts-bay to send persons indicted for murder in that province to another colony, or even to Great-Britain, for trial, whereby such offenders may escape legal punishment; a third for altering the…constitution of government in the province; and a fourth extending the limits of Quebec…whereby great numbers of British freemen are subjected to [French laws]…and establishing an absolute government, and Roman catholick religion, throughout those vast regions that border on the westerly and northerly boundaries of the free protestant English settlements; and a fifth, for the better providing suitable quarter for officers and soldiers in his majesty’s service in North-America….

Had our Creator been pleased to give us existence in a land of slavery, the sense of our condition might have been mitigated by ignorance and habit: But thanks be to his adorable goodness, we were born in…freedom and ever enjoyed our right under the auspices of your royal ancestors, whose family was seated on the British throne to rescue and secure a pious and gallant nation from the popery and despotism of a superstitious and inexorable tyrant….

The apprehension of being degraded into a state of servitude, from the pre-eminent rank of English freemen, while our minds retain the strongest love of liberty, and clearly foresee the miseries preparing for us and our posterity, excites emotions in our breasts, which, though we cannot describe, we should not wish to conceal. Feeling as men, and thinking as subjects in the manner we do, silence would be disloyalty. By giving this faithful information, we do all in our power to promote the great objects of your royal cares, the tranquility of your government, and the welfare of your people…

Many members of the Continental Congress blamed the imperial crisis on the acts of malevolent ministers and implored King George to intercede with Parliament and find some means to preserve English liberties in America. In fact, the king was so invested in the imperial policies that he was unable to serve a mediating role in the conflict. It is interesting to contrast the language of this petition with that of the Declaration of Independence, drafted only twenty months later.