The Revolution Begins

How Do We Know?

The Revolution Begins

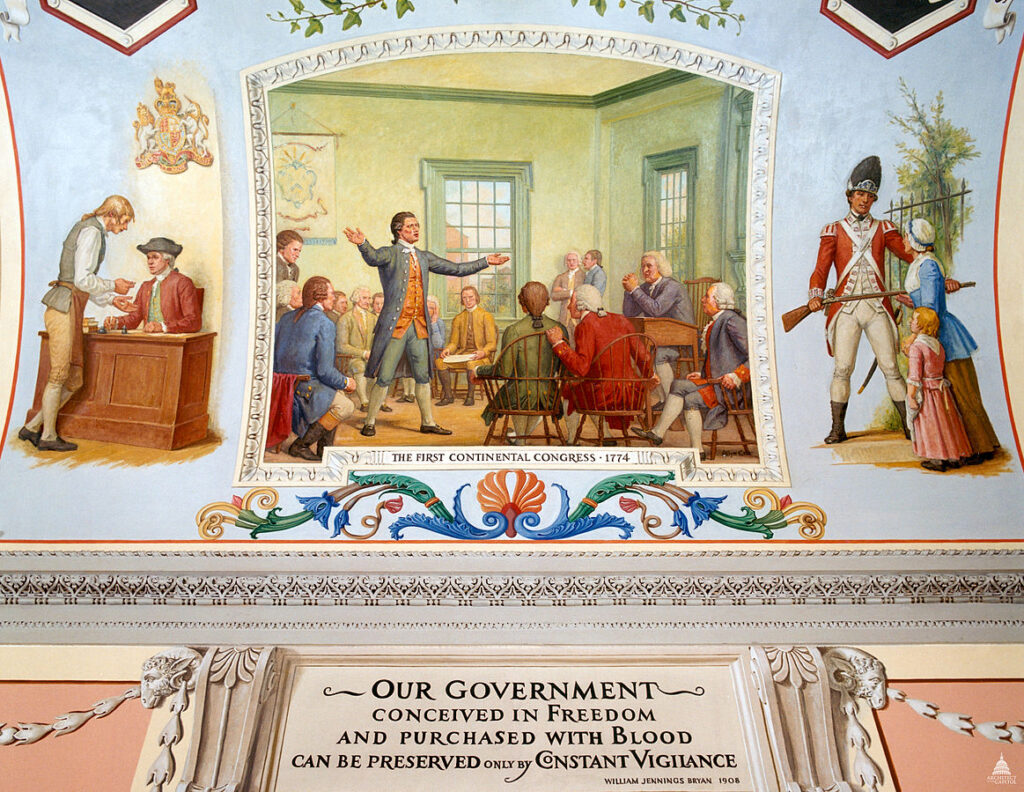

As late as 1774, most colonists did not favor declaring independence from the British Crown. Far from rejecting monarchy, most Americans saw the King as their protector from oppressive acts of Parliament. The delegates to the First Continental Congress, which had assembled in Philadelphia in September 1774, hoped for reconciliation with Britain. They asked Massachusetts Bay colonists, who were the most radical in their opposition to British policies, to avoid involving “all America in the horrors of a civil war.”

In February 1775, Parliament declared Massachusetts to be in a state of rebellion. This declaration permitted soldiers to shoot suspected rebels on sight. In April, British General, Thomas Gage, received secret orders to arrest the ringleaders of colonial unrest. To avoid arrest, colonial leaders fled Boston.

Gage decided to seize and destroy arms that the patriots had stored at Concord, twenty miles northwest of Boston. When Joseph Warren, a Boston patriot, discovered that British troops were on the march, he sent Paul Revere and William Dawes to warn the people about the approaching forces.

At dawn on April 19, the troops reached the town of Lexington, five miles east of Concord. About seventy volunteer soldiers lined the Lexington Green to warn the red-coated British troops not to trespass on the property of freeborn English subjects. A shot rang out — the “shot heard round the world.” The British troops fired. Eight minutemen were killed, and another ten were wounded.

The British continued to Concord, where they searched for hidden arms. At North Bridge, a group of redcoats and minutemen clashed, leaving three redcoats and two minutemen dead. The British then retreated to Boston, while citizen-soldiers fired at the redcoats from behind trees and stone fences.

Even after the battles of Lexington and Concord, the members of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress described themselves as “loyal and dutiful subjects” of the King, who were ready to defend the Crown with their “Lives and Fortunes.” They asked King George III and the British people to protect them against the King’s ministers.

But George III dismissed the colonists’ protestations of loyalty and told Parliament in October 1775 that such claims were “meant only to amuse.”

He noted that the Continental Congress was already assuming the powers of government. It had established an army, appointed officers, and named a commander-in-chief. It had also raised money to support an army by loans and printing money. In addition, it had taken charge of Indian affairs and the post office.

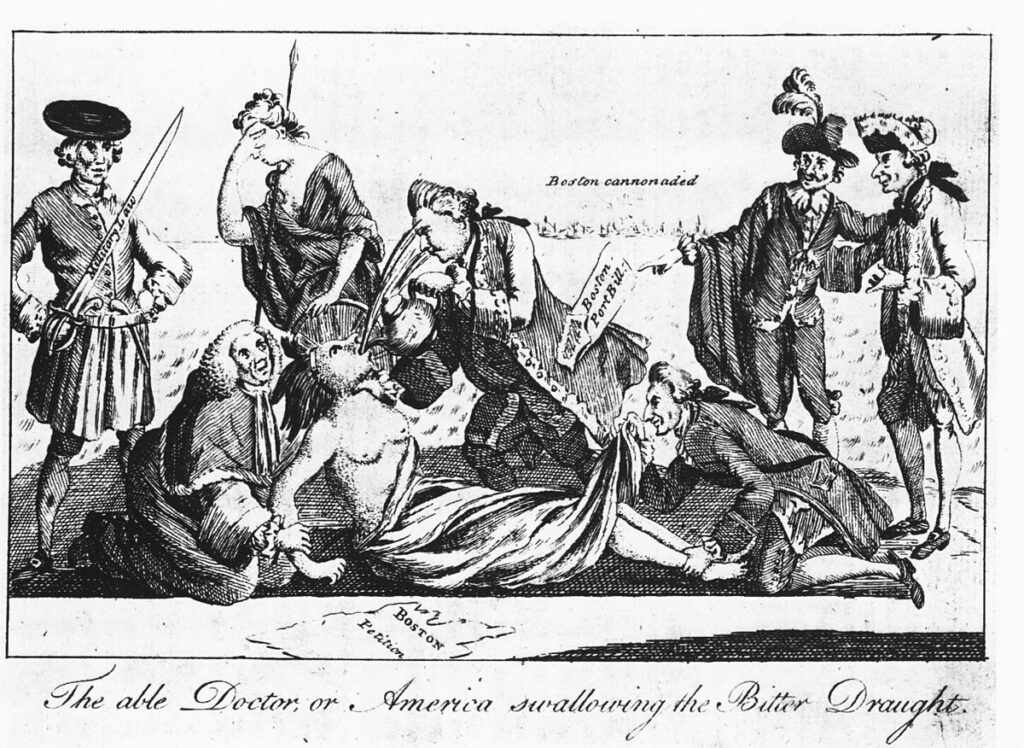

Why Did the Colonists Rebel and the British Resist?

The British Crown misunderstood that the colonists increasingly saw themselves as a separate people, due to their own voice in their own affairs. A series of British political missteps, outright blunders, and heavy-handedness stirred the colonists to become patriots. By 1776, a growing number of Americans, including George Washington, were convinced that Britain was embarked on a systematic plan to strip them of their property and reduce them to slavery. At the same time, Britain feared that if it lost the American colonies, it would lose the entire British Empire. In 1776, Britain did not have thirteen New World colonies, it had thirty. The American Revolution raised the specter of the loss of Ireland and the British West Indies.

Hidden History

The Complexity of the American Revolution

A defining characteristic of the American Revolution is its complexity. The American war for independence was partly a product of the colonists’ sense of a distinctive identity as inhabitants of a republican society. But the Revolution also helped to nurture a sense of a uniquely American identity. The Revolution was a colonial war for independence, but it was also a struggle over “who would rule at home.”

The struggle for American independence was led by prominent lawyers, merchants, and planters. But the Revolution’s success ultimately depended on the willingness of hundreds of thousands of ordinary Americans to risk their lives and economic well-being in the patriot cause. The Revolution represented a conservative effort to preserve liberties that British policies seemed to threaten. But the Revolution was accompanied by social and intellectual transformations that fundamentally altered the nature of American politics and involved ordinary people in politics to an unprecedented degree.

The Revolution was truly multifaceted. There was a rebellion of the colonial gentry against British aristocrats who refused to accept them as equals and who viewed them with condescension. There was also a rebellion by merchants and shippers who chafed at British trade restrictions and royal monopolies. There was a conservative revolution, which sought to defend traditional liberties against British encroachments. There was a radical revolution, inspired by the call for liberty and equality in the Declaration of Independence, which sought to create a society that could serve as a model of freedom for the rest of the world.