America’s Symbols & Icons

History Through…

… America’s Symbols and Icons

From Plymouth Rock and the Liberty Bell to the bald eagle, Uncle Sam, the White House, the Statue of Liberty, and the American flag, certain objects, animals, places, and structures have served as defining symbols of the United States, embodying this society’s basic values, commitments, and collective identity, representing hope, possibility, national unity, and opportunity.

How Has Liberty Been Pictured?

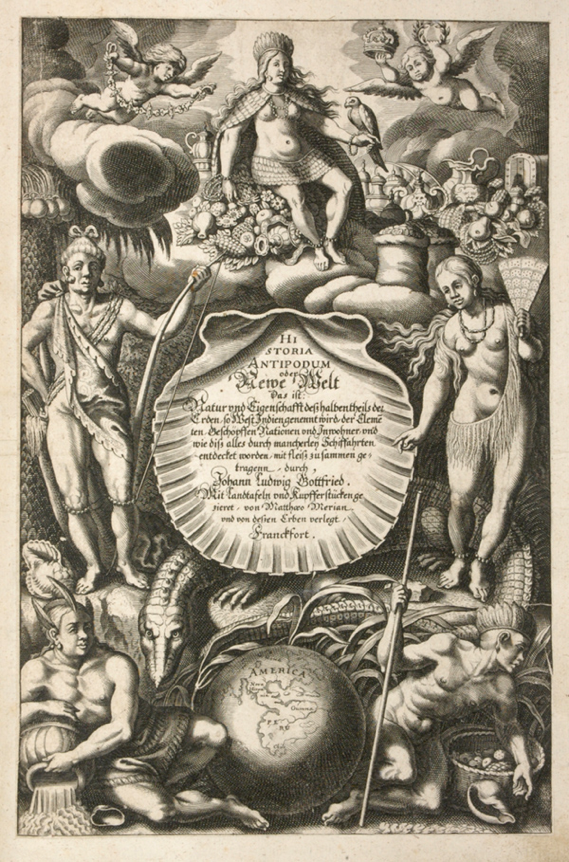

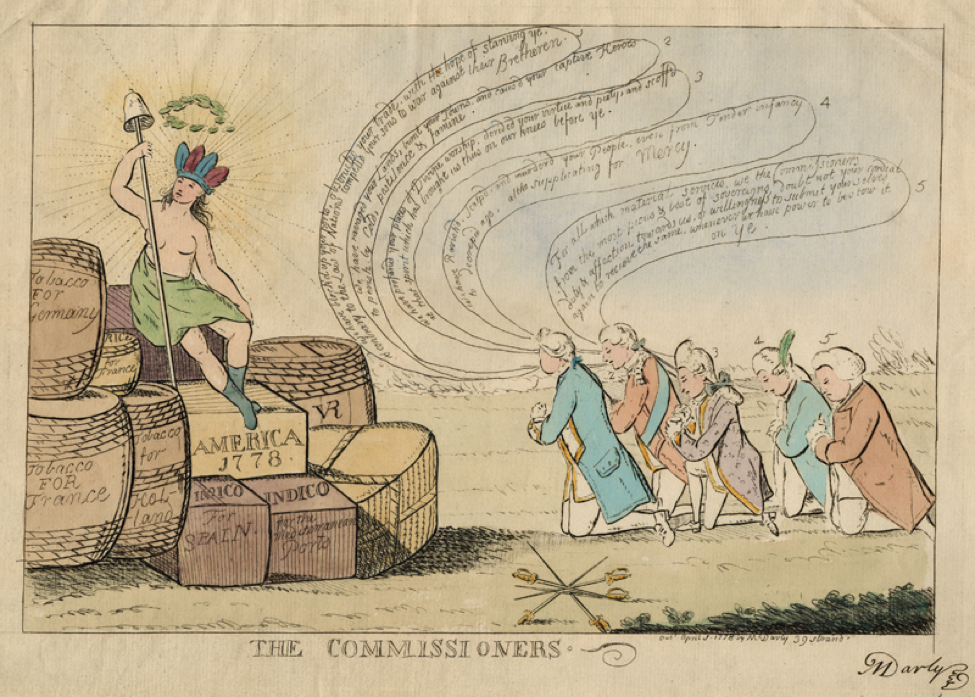

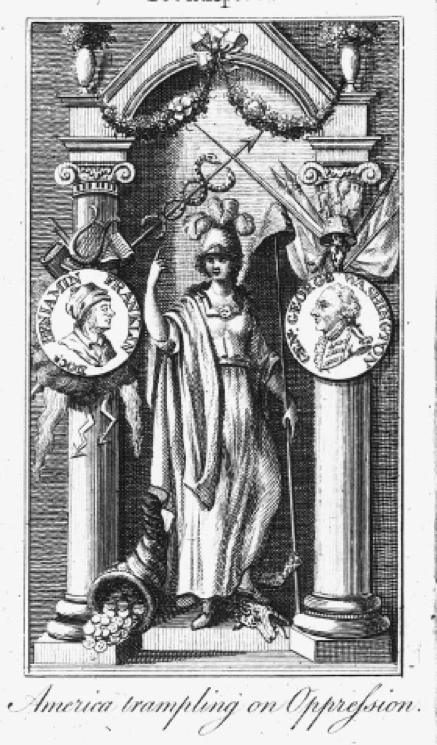

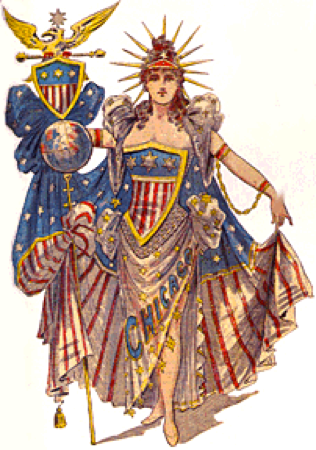

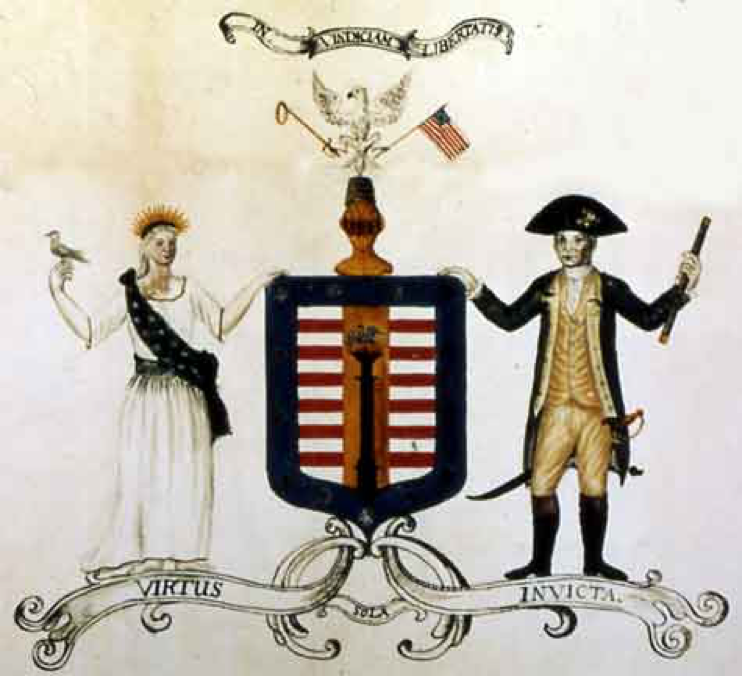

Before there was Uncle Sam, America was depicted as an Indian Queen, an Indian Princess, and a goddess wearing flowing robes. Females were America’s symbols of liberty. Today, this earlier tradition persists, but only marginally. It can be seen, of course, in the Statue of Liberty, the female figure who represents the movie studio, Columbia Pictures, and the march associated with the Vice President, “Hail Columbia.”

Johann Ludwig Gottfried, Historia Antipodum oder Newe Welt vnd Americanische Historien. Frankfurt, 1631.

Adrien Collaert II after Marten de Vos: Personification of America. Europe. 1765-1775. Engraving. 8 3/8″ x 10 3/8″.

British Resentment or the French Fairly Coopt at Louisbourg, etching. Published by T. Bowles, L. Boitard artist; J. June etcher. London: 1755.

Liberty Triumphant, or the Downfall of Oppression, engraving. London: 1774.

The Able Doctor, or America Swallowing the Bitter Draught, in London Magazine, vol. 43., engraving. London: May 1774.

The Commissioners, engraving, printed by Matthew Darly. London: 1778

W.D. Cooper, “America Trampling on Oppression,” The History of North America, E. Newberry: London, 1789, frontispiece in Rare Book and Special Collections Division Library of Congress.

Samuel Jennings (1789-1834). Liberty Displaying the Arts and Sciences, or The Genius of America Encouraging the Emancipation of the Blacks, 1792. Oil on canvas. 60 1/4″ x 74″. Library Company of Philadelphia. Gift of the artist, 1792.

Edward Savage: Liberty in the Form of the Goddess of Youth: Giving Support to the Bald Eagle, 1796.

Mary Green, embroidery, 1804

A picture entitled “The Spirit of 61. God, Our Country and Liberty!” by Currier and Ives circa 1861. Library of Congress

1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago

…Symbols

Americans have long identified America with liberty—invoking such symbols as liberty caps, liberty poles, liberty trees, the liberty bell, and since 1889, the Statue of Liberty.

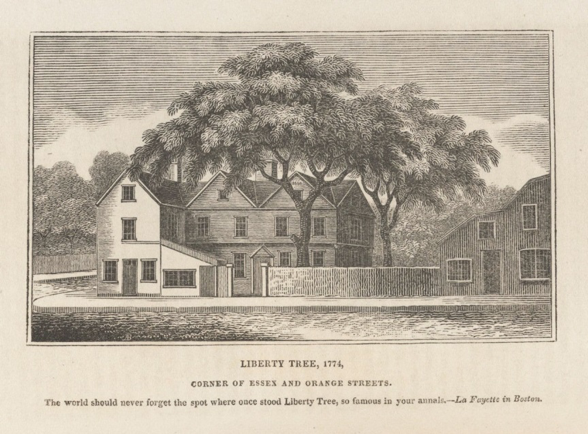

The Liberty Tree in Boston, as illustrated in 1825

Philip Dawe (attributed), The Bostonians Paying the Excise-man, or Tarring and Feathering (1774)

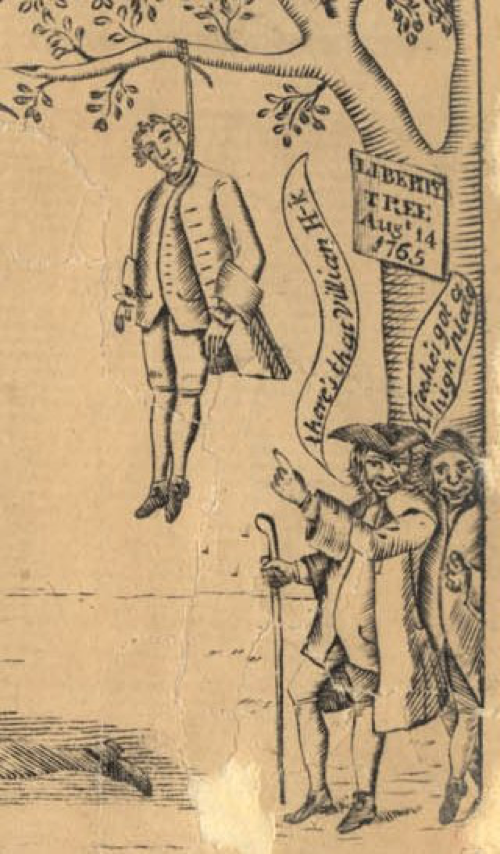

On 1 Nov 1765, Bostonians hung two men in effigy from Liberty Tree. One was George Grenville, the prime minister who had sponsored the Stamp Act. The other, John Huske, a member of Parliament who some thought was responsible for the Stamp Act.

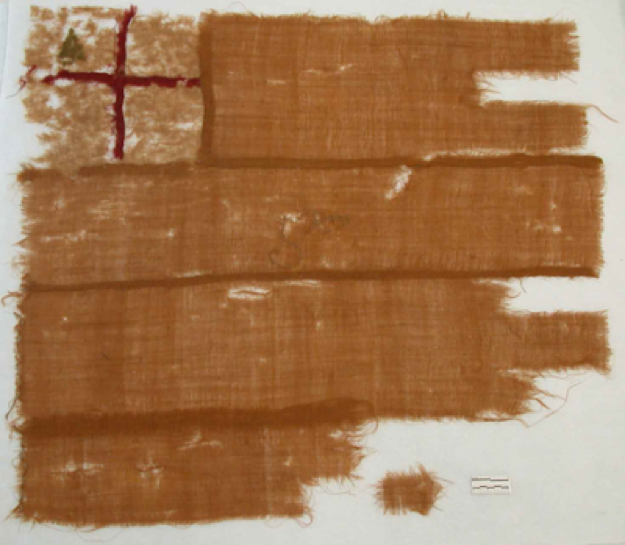

Liberty Tree (or Pine Tree) Flag.

The only surviving flag from the era of the American Revolution. See the tree in the upper left hand corner.

“Raising the liberty pole,” 1776 / painted by F.A. Chapman; engraved by John C. McRae. Painted c. 1875.

Liberty Bell. Cast in 1752. “Proclaim LIBERTY throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof” Leviticus 25:10.

History Through…

…Language

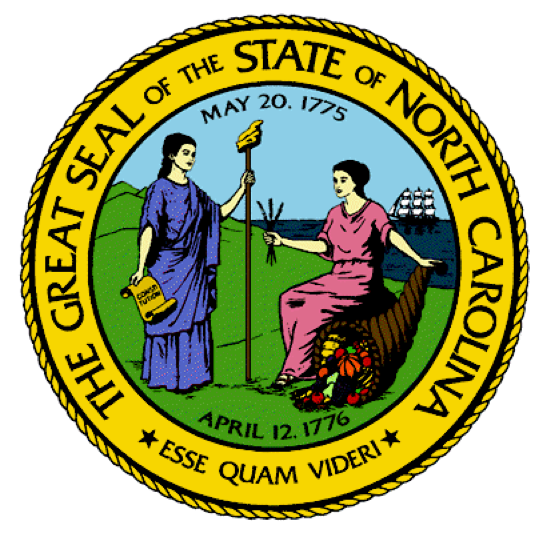

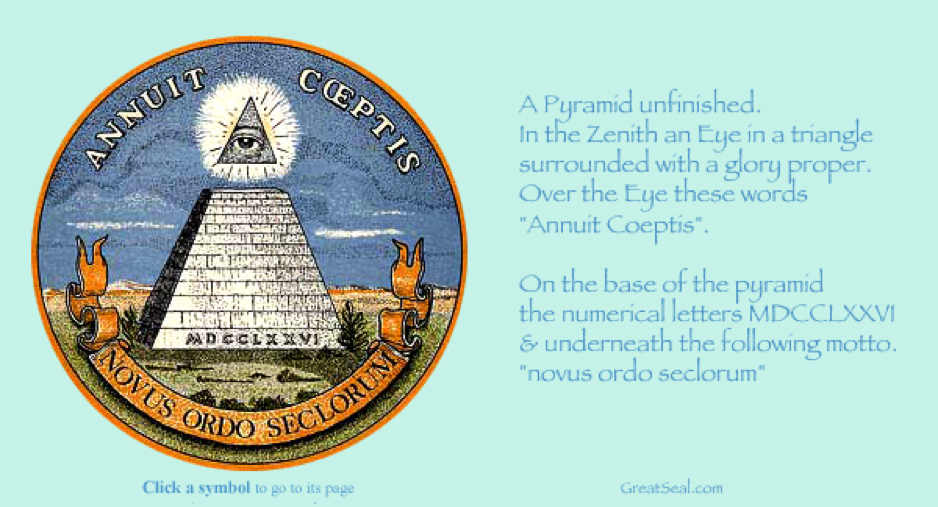

The Great Seal of the United States contains several Latin phrases that translate: “From Many, One” and “A New Order for the Ages.” It also contains, on one side, an eagle with an olive branch and arrows in its talons, and an unfinished pyramid and an eye in a triangle on the inverse side.

This is quite different from the seal recommended by Benjamin Franklin, which depicted the ancient Israelites fleeing their Egyptian captives.

Benjamin Franklin’s Great Seal Design

A Cynic Questions the American Revolution

A journalist raised in Montreal recently mocked the American Revolution. Americans, he claims, tend to romanticize the Revolution, treating it as a struggle for freedom—when, in fact, white American colonists were among the least oppressed, least taxed people in the Western world.

Writing in The New Yorker magazine, Adam Gopnik argued that “The Revolution…was a needless and brutal bit of slaveholders’ panic mixed with Enlightenment argle-bargle, producing a country that was always marked for violence and disruption and demagogy.”

Gopnik makes the argument that the Revolution was led primarily by large slaveholders (and those who would collaborate with them) under a veneer of Enlightenment ideas such as liberty, equality, and popular self-government—ideas that contrasted with a reality of slavery and deep class (and gender) divisions.

Gopnik notes that if Americans looked toward Canada or Australia, they would see that it was possible to separate from Britain peacefully, producing countries that are more equitable, less bellicose and militaristic, and less aggressively jingoistic than the United States.

Gopnik looks particularly fondly at Canada, which is technically a constitutional monarchy under Queen Elizabeth II. Canada’s $20 bill still features the face of the Queen. Canada, he notes, is a far less violent and far more economically equal country than the United States and its has pretty successfully created a bilingual nation, with French and English holding equal weight. Its politics are less bitterly partisan, its population less prone to witch hunts and bouts of paranoia, and its leaders less charismatic and more focused on competent administration.

Gopnik further suggests that without the Revolution, slavery might have been abolished sooner; after all, it was ended peacefully across the British Caribbean in 1834. And with slavery abolished, the United States might well have expanded westward more gradually and less violently, and avoided the Civil War and its violent aftermath.

The Revolution, Gopnik submits, helped produce a culture that tends to celebrates rebels, outlaws, and desperados, which regards government with suspicion, hates taxes, and places an inordinate emphasis on individualism. It also produced a country that treated its indigenous population in a particularly brutal manner. In Canada, in contrast, there were no reservations and white-Indian relations were less conflict-riven.

Of course, without the Revolution there would have been no Declaration of Independence, with its stress on equality and natural rights, and no Bill of Rights.