Immigration Begins

Reading Maps

Immigration Begins

During the summer of 1845, a “blight of unusual character” devastated Ireland’s potato crop, the basic staple of the Irish diet. A few days after potatoes were dug from the ground, they began to turn into a slimy, decaying, blackish “mass of rottenness.” Expert panels, convened to investigate the blight’s cause, suggested that it was a result of “static electricity” or the smoke that billowed from railroad locomotives or “mortiferous vapours” rising from underground volcanoes. In fact, the cause was a fungus that had traveled from America to Ireland.

“Famine fever”—dysentery, typhus, and infestations of lice—soon spread through the Irish countryside. Observers reported seeing children crying with pain and looking “like skeletons, their features sharpened with hunger and their limbs wasted, so that there was little left but bones, their hands and arms.” Masses of bodies were buried without coffins, a few inches below the soil.

Over the next ten years, 750,000 Irish died and another two million left their homeland for Great Britain, Canada, and the United States. Freighters, which carried American and Canadian timber to Europe, offered fares as low as $17 to $20 between Liverpool and Boston—fares subsidized by English landlords eager to be rid of the starving peasants. As many as ten percent of the emigrants perished while still at sea. In 1847, 40,000 (or twenty percent) of those who set out from Ireland died along the way. “If crosses and tombs could be erected on water,” wrote the U.S. commissioner for emigration, “the whole route of the emigrant vessels from Europe to America would long since have assumed the appearance of a crowded cemetery.”

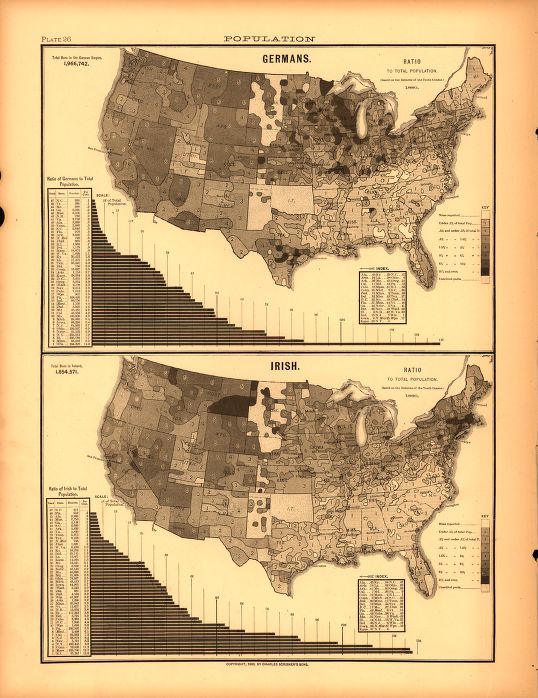

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, only about 5,000 immigrants arrived in the United States each year. During the 1830s, however, immigration climbed sharply as 600,000 immigrants poured into the country. This figure jumped to 1.7 million in the 1840s, when harvests all across Europe failed, and reached 2.6 million in the 1850s. Most of these immigrants came from Germany, Ireland, and Scandinavia, pushed from their homelands by famine, evicted from farmlands by landlords, displaced by political unrest, and unemployed by the destruction of traditional handicrafts by factory enterprises. Attracted to the United States by the prospects of economic opportunity and political and religious freedom, many dispossessed Europeans braved the voyage across the Atlantic.

Each immigrant group migrated for its own distinct reasons and adapted to American society in its own unique ways. Poverty forced most Irish immigrants to settle in their port of origin. By the 1850s, the Irish comprised half the population of New York and Boston. Young, unmarried, Catholic, and largely of peasant background, the immigrants faced the difficult task of adapting to an urban and a predominantly Protestant environment. Confronting intense discrimination in employment, most Irish men found work as manual laborers, while Irish women took jobs mainly in domestic service. Discrimination had an important consequence. It encouraged Irish immigrants to become actively involved in politics. With a strong sense of ethnic identity, high rates of literacy, and impressive organizational talents, Irish politicians played an important role in the development of modern American urban politics.

Unlike Irish immigrants, who settled primarily in Northeastern cities and engaged in politics, German immigrants tended to move to farms or frontier towns in the Midwest and were less active politically. While some Germans fled to the United States to escape political persecution following the revolutions of 1830 and 1848, most migrated to sustain traditional ways of life. The industrial revolution severely disrupted traditional patterns of life for German farmers, shopkeepers, and practitioners of traditional crafts like baking, brewing, and carpentering. In the Midwest’s farmland and frontier cities, including Cincinnati and St. Louis, they sought to reestablish old German lifeways, setting up German fraternal lodges, coffee circles, and educational and musical societies.

German immigrants carried important aspects of German culture with them, which quickly became integral parts of American culture, including the Christmas tree and the practice of Christmas gift-giving, the kindergarten, and the gymnasium. Given Germany’s strong educational and craft traditions, it is not surprising that German immigrants would be particularly prominent in the fields of engineering, optics, drug manufacture, and metal- and tool-making, as well as in the labor movement.

Historical Facts & Fiction

The Divided North

During the decades preceding the Civil War, it was an article of faith among Northerners that their society offered unprecedented economic equality and opportunity, and was free of rigid class divisions and glaring extremes of wealth and poverty. It was a land where even a “humble mechanic” had “every means of winning independence which are extended only to rich monopolists in England.” How accurate is this picture of the pre–Civil War North as a land of opportunity, where material success was available to all?

In fact, the percentage of wealth held by those at the top of the economic hierarchy appears to have increased substantially before the Civil War. While the proportion of wealth controlled by the richest ten percent rose from fifty percent in the 1770s to seventy percent in 1860, the real wages of unskilled northern workers stagnated or, at best, rose modestly. By 1860, half of all free whites held fewer than one percent of the North’s real and personal property, while the richest one percent owned twenty-seven percent of the region’s wealth—a level of inequality comparable to that found in early nineteenth-century Europe and greater than that found in the United States today. In towns as different as Stonington, Connecticut, and Chicago, Illinois, between two-thirds and three-quarters of all households owned no property.

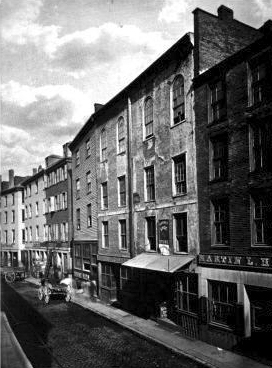

The first stages of industrialization and urbanization in the North, far from diminishing social inequality, actually widened class distinctions and intensified social stratification. At the top of the social and economic hierarchy was an elite class of families, linked together by intermarriage, membership in exclusive social clubs, and residence in exclusive neighborhoods, as rich as the wealthiest families of Europe. At the bottom were the working poor—immigrants, casual laborers, African Americans, widows, and orphans—who might be thrown out of work or their home at any time. Poor, propertyless unskilled laborers composed a vast floating population, which trekked from city to city in search of work. They congregated in urban slums like Boston’s Ann Street and New York’s Five Points, where starving children begged for pennies and haggard prostitutes plied their trade.

Between these two extremes were family farmers and a rapidly expanding urban middle class of shopkeepers, merchants, bankers, agents, and brokers. This was a highly mixed group that ranged from prosperous entrepreneurs and professionals to hard-pressed journeymen, who found their skills increasingly obsolete.

Does this mean that the pre–Civil War North was not the fluid, “egalitarian” society that many Northerners claimed? The answer is a qualified “no.” In the first place, the North’s richest individuals, unlike Europe’s aristocracy, worked for a living, engaging in commerce, insurance, finance, shipbuilding, manufacturing, landholding, real estate, and professions. More important, wealthy Northerners publicly rejected the older Hamiltonian notion that the rich and well-born were superior to the masses of people. During the early decades of the nineteenth century, wealthy Northerners shed the wigs, knee breeches, ruffled shirts, and white-topped boots that had symbolized high social status in colonial America and began to dress like other men, signaling their acceptance of an ideal of social equality. One wealthy Northerner succinctly summarized the new ideal: “These phrases, the higher orders, and lower orders, are of European origin, and have no place in our Yankee dialect.”

Above all, it was the North’s relatively high rates of economic, geographical, and social mobility that gave substance to a widespread belief in equality of opportunity. Although few rich men were truly “self-made” men who had climbed from “rags to riches,” there were many dramatic examples of upward mobility and countless instances of more modest climbs up the ladder of success. Industrialization rapidly increased the number of nonmanual jobs in commerce, industry, and the professions. There were new opportunities for lawyers, bookkeepers, business managers, brokers, and clerks. Giving additional reinforcement to the belief in opportunity was a remarkable rate of physical mobility. Each decade, fully half the residents of Northern communities moved to a new town.

Even at the bottom of the economic hierarchy, prospects for advancement increased markedly after 1850. During the 1830s and 1840s, less than one unskilled worker in ten managed in the course of a decade to advance to a white-collar job. After 1850, the percentage doubled. The sons of unskilled laborers were even more likely to advance to skilled or white-collar employment. Even the poorest unskilled laborers often were able to acquire a house and a savings account as they grew older, and their children did better yet. It was the reality of physical and economic mobility that convinced the overwhelming majority of Northerners that they lived in a uniquely open society, in which differences in wealth or status were the result of hard work and ambition.