The Introduction of the Factory System

The Introduction of the Factory System

In 1789, the Pennsylvania legislature placed an advertisement in British newspapers offering a cash bounty to any English textile worker who would migrate to the state. Samuel Slater, who was just finishing an apprenticeship in a Derbyshire textile mill, read the ad. He went to London, booked passage to America, and landed in Philadelphia. There, he learned that Moses Brown, a Quaker merchant, had just completed a mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, and needed a manager. Slater applied for the job and received it, along with a promise that if he made the factory a success he would receive all the business’s profits, less the cost and interest on the machinery.

On December 21, 1790, the mill opened. Seven boys and two girls, all between the ages of seven and twelve, operated the little factory’s 72 spindles. Slater soon discovered that these children, “constantly employed under the immediate inspection of a [supervisor],” could produce three times as much as whole families working in their homes. To keep the children awake and alert, Slater whipped them with a leather strap or sprinkled them with water. On Sundays, the children attended a special school Slater founded for their education.

The opening of Slater’s mill marked the beginning of a widespread movement to consolidate manufacturing operations under a single roof. During the last years of the eighteenth century, merchants and master craftspeople who were discontented with the inefficiencies of their workforce created the nation’s first modern factories. Within these centralized workshops, employers closely supervised employees, synchronized work to the clock, and punished infractions of rules with heavy fines or dismissal. In 1820, only 350,000 Americans worked in factories or mills. Four decades later, on the eve of the Civil War, the number had soared to two million.

For an inexpensive and reliable labor force, many factory owners turned to child labor. During the early phases of industrialization, textile mills and agricultural tool, metal goods, nail, and rubber factories had a ravenous appetite for cheap teenage laborers. In many mechanized industries, from a quarter to over half of the workforce was made up of young men or women under the age of twenty.

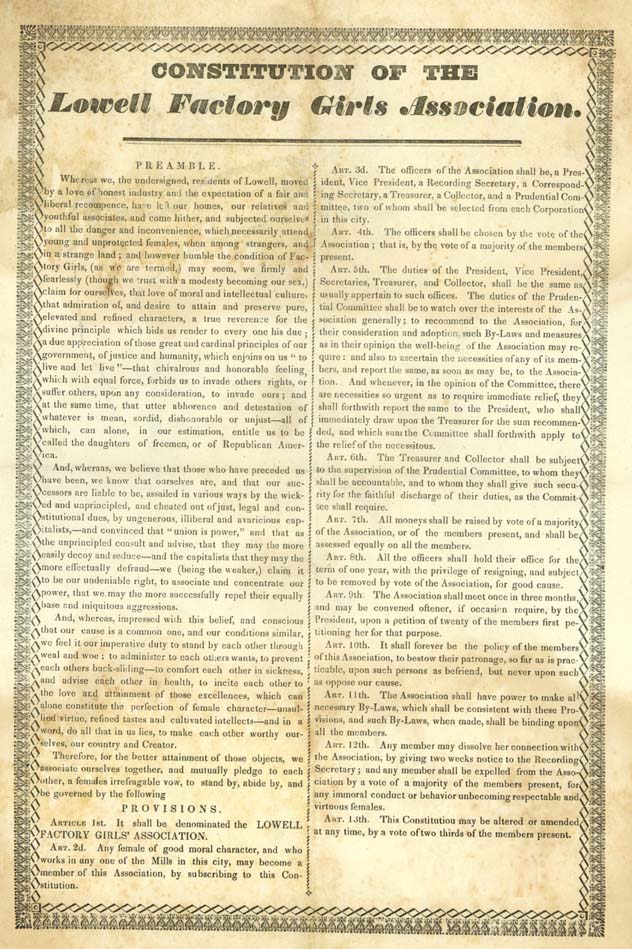

During the first half of the nineteenth century, unmarried women made up a majority of the workforce in cotton textile mills and a substantial minority of workers in factories manufacturing ready-made clothing, hats, and shoes. Women were also employed in significant numbers in the manufacture of buttons, furniture, gloves, gunpowder, shovels, and tobacco.

Unlike farm work or domestic service, employment in a mill offered female companionship and an independent income. Wages were twice what a woman could make as a seamstress, tailor, or schoolteacher. Furthermore, most mill girls viewed the work as only temporary before marriage. Most worked in the mills fewer than four years, and frequently interrupted their stints in the mill for several months at a time with trips back home.

By the 1830s, increasing competition among textile manufacturers caused deteriorating working conditions that drove native-born women out of the mills. Employers cut wages, lengthened the workday, and required mill workers to tend four looms instead of just two. Hannah Borden, a Fall River, Massachusetts, textile worker, was required to have her loom running at 5 A.M. She was given an hour for breakfast and half an hour for lunch. Her workday ended at 7:30 P.M., 14 1⁄2 hours after it had begun. For a 6-day workweek, she received between $2.50 and $3.50.

The mill girls militantly protested the wage cuts. In 1834 and again in 1836, the mill girls went out on strike. An open letter spelled out the workers’ complaints: “sixteen females [crowded] into the same hot, ill-ventilated attic”; a workday “two or three hours longer…than is done in Europe”; and workers compelled to “stand so long at the machinery…that varicose veins, dropsical swelling of the feet and limbs, and prolapsus uter[us], diseases that end only with life, are not rare but common occurrences.”

During the 1840s, fewer and fewer native-born women were willing to work in the mills. “Slavers,” which were long, black wagons that criss-crossed the Vermont and New Hampshire countryside in search of mill hands, arrived empty in Rhode Island and Massachusetts mill towns. Increasingly, employers replaced the native-born mill girls with a new class of permanent factory operatives: immigrant women from Ireland.

The Laboring Poor

In January 1850, police arrested John McFeaing in Newburyport, Massachusetts, for stealing wood from the wharves. McFeaing pleaded necessity and a public investigation was conducted. Investigators found McFeaing’s wife and four children living “in the extremity of misery. The children were all scantily supplied with clothing and not one had a shoe to his feet. There was not a stick of firewood or scarcely a morsel of food in the house, and everything betokened the most abject want and misery.” McFeaing’s predicament was not uncommon at that time.

The quickening pace of trade and finance during the early-nineteenth century not only increased the demand for middle-class clerks and shopkeepers, it also dramatically increased demand for unskilled workers, who earned extremely low incomes and led difficult lives. In 1851, Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, estimated the minimum weekly budget needed to support a family of five. Essential expenditures for rent, food, fuel, and clothing amounted to $10.37 a week. In that year, a shoemaker or a printer earned just $4.00 to $6.00 a week, a male textile operative $6.50 a week, and an unskilled laborer just $1 a week. The only manual laborers able to earn Greeley’s minimum were blacksmiths and machinists.

Frequent unemployment compounded the problems of the unskilled. In Massachusetts, upward of 40 percent of all workers were out of a job for part of a year, usually for four months or more. Fluctuations in demand, inclement weather, interruptions in transportation, technological displacement, fire, injury, and illness all could leave workers jobless.

To provide protection against temporary unemployment, many working-class families scrimped and saved to buy a house or maintain a garden. In Newburyport, Massachusetts, many workers bought farm property on the edge of town. On New York City’s East Side, many families kept goats and pigs. Ownership of a house was a particularly valuable source of security, since a family could always obtain extra income by taking in boarders and lodgers.

Labor Protests

In 1806, journeyman shoemakers in New York City organized one of the nation’s first labor strikes. The workers’ chief demands were not higher wages and shorter hours. Instead, they protested the changing conditions of work. They staged a “turn-out” or “stand-out,” as a strike was then called, to protest the use of cheap unskilled and apprentice labor and the subdivision and subcontracting of work. The strike ended when a court ruled that a labor union was guilty of criminal conspiracy if workers struck to obtain wages higher than those set by custom. The court found the journeyman shoemakers guilty and fined them $1 plus court costs.

By the 1820s, a growing number of journeymen were organizing to protest employer practices that were undermining the independence of workers, reducing them to the status of “a humiliating servile dependency, incompatible with the inherent natural equality of men.” Unlike their counterparts in Britain, American journeymen did not protest against the introduction of machinery into the workplace. Instead, they vehemently protested wage reductions, declining standards of workmanship, and the increased use of unskilled and semiskilled workers. Journeymen charged that manufacturers had reduced “them to degradation and the loss of that self-respect which had made the mechanics and laborers the pride of the world.” They insisted that they were the true producers of wealth and that manufacturers, who did not engage in manual labor, were unjust expropriators of wealth. In 1834, journeymen established the National Trades’ Union, the first national organization of American wage earners. By 1836, union membership had climbed to 300,000.

Despite bitter employer opposition, some gains were made. In 1842, in the landmark case Commonwealth v. Hunt, the Massachusetts Supreme Court established a new precedent by recognizing the right of unions to exist. In addition to establishing the nation’s first labor unions, journeymen also formed political organizations, known as Working Men’s parties, as well as mutual benefit societies, libraries, educational institutions, and producers’ and consumers’ cooperatives. Working men and women published at least 68 labor papers, and they agitated for free public education, reduction of the workday, and abolition of capital punishment, state militias, and imprisonment for debt. Following the Panic of 1837, land reform was one of labor’s chief demands. One hundred sixty acres of free public land for those who would actually settle the land was the demand, and “Vote Yourself a Farm” became the popular slogan.

The Movement for a Ten-Hour Day

Labor’s greatest success was a campaign to establish a ten-hour workday in most major Northeastern cities. In 1835, carpenters, masons, and stonecutters in Boston staged a seven-month strike in favor of a ten-hour day. The strikers demanded that employers reduce excessively long hours worked in the summer and spread them throughout the year.

Quickly, the movement for a ten-hour workday spread to Philadelphia, where carpenters, bricklayers, plasterers, masons, leather dressers, and blacksmiths went on strike.

Textile workers in Paterson, New Jersey, were the first factory operatives to strike for a reduction in work hours. Soon, women textile operatives in Lowell added their voices to the call for a ten-hour day, contending that such a law would “lengthen the lives of those employed, by giving them a greater opportunity to breathe the pure air of heaven” as well as provide “more time for mental and moral cultivation.”

In 1840, the federal government introduced a ten-hour workday on public works projects. In 1847, New Hampshire became the first state to adopt a ten-hour day law. It was followed by Pennsylvania in 1848. Both states’ laws, however, included a clause that allowed workers to voluntarily agree to work more than a ten-hour day. Despite the limitations of these state laws, agitation for a ten-hour day did result in a reduction in the average number of hours worked, to approximately 11 1⁄2 by 1850.