Political & Cultural Transformations

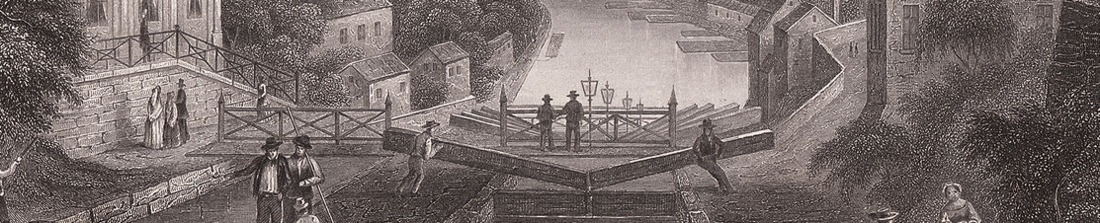

The Transformation of the Rural Countryside

In 1790, most farm families in the rural North produced most of what they needed to live. Instead of using money to purchase necessities, families entered into complex exchange relationships with relatives and neighbors and bartered to acquire the goods they needed. To supplement their meager incomes, farm families often did piecework for shopkeepers and craftsmen. In the late-eighteenth-century these “household industries” provided work for thousands of men, women, and children in rural areas. Shopkeepers or master craftsmen supplied farm families with raw materials and paid them piece rates to produce such items as linens and farm utensils.

Between 1790 and the 1820s, a new pattern emerged. Subsistence farming gave way to commercial agriculture as farmers increasingly began to grow cash crops for sale and used the proceeds to buy goods produced by others. In New Hampshire, farmers raised sheep for wool. In western Massachusetts, they began to fatten cattle and pigs for sale to Boston. In eastern Pennsylvania, they specialized in dairy products.

After 1820, the household industries that had employed thousands of women and children began to decline. They were replaced by manufacturing in city shops and factories. New England farm families began to buy their shoes, furniture, cloth, and sometimes even their clothes ready-made. Small rural factories closed their doors, and village artisans who produced for local markets found themselves unable to compete against cheaper city-made goods. As local opportunities declined, many long-settled farm areas suffered sharp population losses. Convinced that “agriculture is not the road to wealth, nor honor, nor to happiness,” thousands of young people left the fields for cities.

The Disruption of the Artisan System of Labor

In the late-eighteenth century, the North’s few industries were small. Skilled craftspeople, known as artisans or mechanics, performed most manufacturing in small towns and larger cities. These craftspeople manufactured goods in traditional ways—by hand in their own homes or in small shops located nearby—and marketed the goods they produced. Mathew Carey, a Philadelphia newspaperman, personified the early nineteenth-century artisan-craftsman. He not only wrote articles and editorials that appeared in his newspaper, he also set the paper’s type, operated the printing press, and hawked the newspaper.

The artisan class was divided into three subgroups. At the highest level were self-employed master craftspeople. They were assisted by skilled journeymen, who owned their own tools but lacked the capital to set up their own shops, and by apprentices, teenage boys who typically worked for three years in exchange for training in a craft.

Urban artisans did not draw a sharp separation between home and work. A master shoemaker might make shoes in a 10-foot square shed located immediately in back of his house. A printer would bind books or print newspapers in a room below his family’s living quarters. Typically, a master craftsperson lived in the same house with his assistants. The household of Everard Peck, a Rochester, New York, publisher, was not unusual. It included his wife, his children, his brother, his business partner, a day laborer, and four journeyman printers and bookbinders.

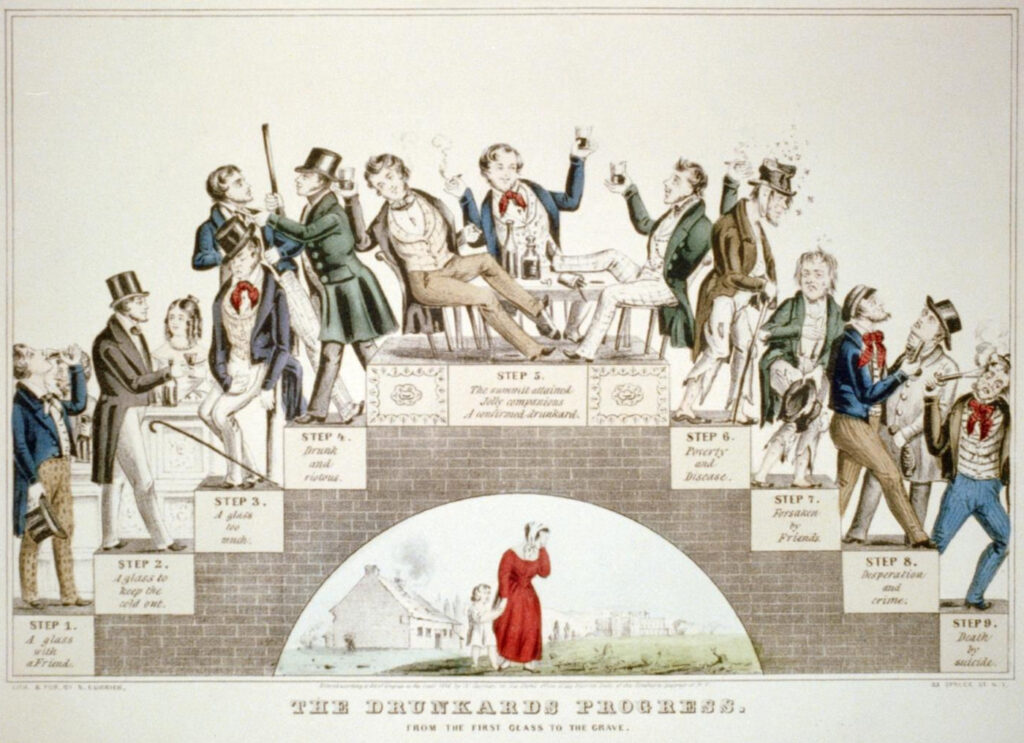

Nor did urban artisans draw a sharp division between work and leisure. Work patterns tended to be irregular and were frequently interrupted by leisure breaks during which masters and journeymen would drink whiskey or other alcoholic beverages. During slow periods or periodic layoffs, workers enjoyed fishing trips and sleigh rides or cockfights, as well as drinking and gambling at local taverns. Artisans often took unscheduled time off to attend boxing matches, horse races, and exhibitions by traveling musicians and acrobats.

The first half of the nineteenth century witnessed the decline of the artisan system of labor. Skilled tasks, previously performed by artisans, were divided and subcontracted to less expensive unskilled laborers. Small shops were replaced by large “machineless” factories, which made the relationship between employer and employee increasingly impersonal. Many master craftspeople abandoned their supervisory role to foremen and contractors and substituted unskilled teenage boys for journeymen. Words like employer, employee, boss, and foreman—descriptive of the new relationships—began to be widely used.

Between 1790 and 1850 the work process—especially in the building trades, printing, and such rapidly expanding consumer-oriented manufacturing industries as tailoring and shoemaking—was radically reorganized. The changes in the shoemaking industry in Rochester, New York, during the 1820s and 1830s illustrate this process. Instead of producing an entire shoe, a master would fit a customer, rough-cut the leather uppers, and then send the uppers and soles to a boardinghouse, where a journeyman would shape the leather. Then, the journeyman would send the pieces to a binder, a woman who worked in her home, who would sew the shoes together. Finally, the binder would send the shoe to a store for sale to a customer. Tremendous gains in productivity sprang from the division and specialization of labor.

By 1850, the older household-based economy, in which assistants lived in the homes of their employers, had disappeared. Young men moved out of rooms in their master’s home and into hotels or boardinghouses in distinct working-class neighborhoods. The older view that workers should be attached to a particular master, who would supervise their behavior and assume responsibility for their welfare, declined. This paternalistic view was replaced by a new conception of labor as a commodity, like cotton, that could be acquired or disposed of according to the laws of supply and demand.

Transforming the American Family

Far from being a stable, unchanging institution, the family is as enmeshed in the historical process as any other social institution. The family’s roles and functions, size and composition, and emotional and power dynamics have all changed dramatically over time.

Dramatically new patterns of family life emerged during the early nineteenth century. There was a new urban working class family and a new urban middle-class family.

The quickening pace of commerce during the early-nineteenth century not only increased the demand for middle-class clerks and shopkeepers, but also unskilled and skilled manual workers, such as carters, coal heavers, day laborers, delivery people, dockworkers, packers, and porters. Manual workers earned extremely low incomes and in many of these families, wives and children were forced to work to maintain even a low standard of living.

Typically, a male laborer earned two-thirds of his family’s income. The other third was earned by his wife and children. Many married women performed work in the home, such as embroidery, tailoring, or laundry. The wages of children were critical for a working-class family’s standard of living. Children under the age of fifteen contributed about twenty percent of their family’s income. Older children were expected to defer marriage, to remain at home, and to contribute to the family’s income.

During the early-nineteenth century, a new kind of urban middle-class family began to emerge as the workplace moved some distance from the household and as many of married women’s productive tasks were assumed by unmarried women working in factories.

In urban middle-class families, the father was expected to be the family’s sole breadwinner. He left home to go to work while his wife was expected to stay home. Among the urban middle class, a new ideal of marriage emerged, based primarily on companionship and affection. A new division of domestic roles appeared, which assigned the wife to care full-time for her children and to maintain the home. A new conception of childhood arose that looked at children not as little adults, but as special creatures who needed attention, love, and time to mature.

Spouses began to display affection more openly, calling each other “honey” or “dear.” Parents began to keep their children home longer than in the past. By the mid-nineteenth century, a new emphasis on family privacy could be seen in the expulsion of apprentices from the middle-class home and the increasing separation of servants from the family.

The new urban middle class defined itself by a strict segregation of sexual spheres, intense mother-child bonds, and the idea that children needed to be protected from the corruptions of the outside world. Even at its inception, however, this new family form was beset by certain latent tensions. One source of tension involved the role of the father, who was becoming more psychologically separate from his family. Although many fathers thought of themselves as breadwinners and household heads, and their wives and children as their dependents, in fact many men’s connection to their family was becoming essentially economic. They might serve as disciplinarians of last resort, but mothers replaced fathers as the primary parent.

Another source of tension involved women’s domestic roles. In their youth, women received an unprecedented degree of freedom; increasing numbers attended school and worked, at least temporarily, outside of a family unit. After marriage, however, women were expected to sacrifice their individuality for their family’s sake. In a society that attached increasing value to individualism and equality, the expectation that women should subordinate themselves to their husbands and children was a source of stress. Women’s subordinate status was cloaked with an ideology that viewed women as purer and more caring than men, but the contradiction with the ideal of equality remained.

A third source of tension involved the changing status of children, who remained home far longer than in the past, often into their late teens and twenties. The emerging ideal required a protected childhood, shielding children from knowledge of death, sex, and violence. While in theory families were training children for independence, in reality children received fewer opportunities than in the past to express their growing maturity. The result was that the transition from childhood and youth to adulthood became more disjunctive and riven with conflict.

These underlying contradictions were apparent in three striking developments: a sharp fall in the birth rate, a marked and steady rise in the divorce rate, and a heightened cultural awareness of domestic violence.

The early-nineteenth century saw the beginnings of a sharp fall in the birth rate. Instead of giving birth to seven to ten children, middle-class mothers by the end of the century gave birth to only three. The reduction in birthrates did not depend on new technologies. Rather, it reflected the view that women were not childbearing chattel and that children were no longer economic assets. An emerging ideology deemed children to be priceless, but the fact remained that the young now required greater parental investments in the form of education and other inputs.

During the early and mid-nineteenth century, the divorce rate also began to rise, as judicial divorce replaced legislative divorce and as many states adopted permissive divorce statutes. If marriages were to rest on mutual affection, then divorce had to serve as a safety valve for loveless and abusive marriages. In 1867, the country had ten thousand divorces, and the rate rose steadily from 3.1 per hundred marriages in 1870, to 4.5 per hundred in 1880, to 5.9 per hundred in 1890.

A growing awareness of wife-beating and child abuse also occurred in the early-nineteenth century, which may have reflected an actual increase in assaults and murders committed against blood relatives. As families became less subject to communal oversight, as traditional assumptions about patriarchal authority were challenged, and as an expanding market economy produced new kinds of stress, the family could become an arena of explosive tension, conflict, and violence. Reform movements, such as temperance, abolition, and women’s rights helped to identify family violence as a social problem.

Transforming American Law

The growth of an industrial economy in the United States required a shift in American law. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, American law was rooted in concepts that reflected the values of a slowly changing, agricultural society. The law presumed that goods and services had a just price, independent of supply and demand. Courts forbade many forms of competition and innovation in the name of a stable society. Courts and judges legally protected monopolies and prevented lenders from charging “usurous” rates of interest. The law allowed property owners to sue for damages if a mill was built upstream, and it flooded their land or impeded their water supply.

After 1815, however, the American legal system increasingly favored economic growth, profit, and entrepreneurial enterprise. Courts increasingly viewed risk and profit as beneficial.

In the 1810s and 1820s, American law shifted from a premarket to a market economy perspective. By the 1820s, courts, particularly in the Northeast, had begun to abandon many traditional legal doctrines that stood in the way of a competitive market economy. Courts dropped older doctrines that assumed that goods and services had an objective price, independent of supply and demand. Courts rejected many usury laws, which limited interest rates, and struck down legal rules that prevented tenants from making alterations on a piece of land, including the addition of a building or clearing of trees. Courts increasingly held that only the market could determine interest rates or prices or the equity of a contract.

To promote rapid economic growth, courts and state legislatures gave new powers and privileges to private firms. Companies building roads, bridges, canals, and other public works were given the power to appropriate land. Private firms were allowed to avoid legal penalties for fires, floods, or noise they caused on the grounds that the companies served a public purpose. Courts also reduced the liability of companies for injuries to their own employees, ruling that an injured party had to prove negligence or carelessness on the part of an employer in order to collect damages. The legal barriers to economic expansion had been struck down.