The Industrial Revolution

Early Industrialization

In the 1820s and 1830s, America became the world’s leader in adopting mechanization, standardization, and mass production. Manufacturers began to adopt labor saving machinery that allowed workers to produce more goods at lower costs. So impressed were foreigners with these methods of manufacture that they called them the “American system of production.”

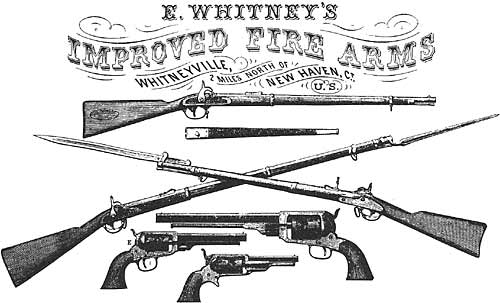

The single most important figure in the development of the American system was Eli Whitney, the inventor of the cotton gin. In 1798, Whitney persuaded the U.S. government to award him a contract for 10,000 muskets to be delivered within two years. At the time Whitney made his offer, the federal arsenal at Springfield, Massachusetts, was capable of producing only 245 muskets in two years. Since Whitney had no factory and no experience making guns, his offer seemed preposterous.

Whitney proposed manufacturing muskets according to a “new principle,” which would enable an unskilled worker to produce muskets faster than those made by a gunsmith. Until then, rifles had been manufactured by skilled artisans, who made individual parts by hand and then carefully fitted the pieces together. Whitney’s idea was to develop precision machinery to make parts that would be interchangeable from one gun to another. For months, Whitney struggled to develop drill presses, lathes, cutters, and grinders that would allow a worker with little manual skill to manufacture identical gun parts. The first year he produced 500 muskets.

In 1801, in order to get an extension on his contract, Whitney demonstrated his new system of interchangeable parts to President John Adams and Vice President Thomas Jefferson. He disassembled ten muskets and put ten new muskets together out of the individual pieces. His system was a success. In fact, the muskets used in the demonstration were not assembly line models, they had been carefully hand-fitted beforehand.

Other industries soon adopted the “American system of manufacturing.” As early as 1800, manufacturers of wooden clocks began to use interchangeable parts. Makers of sewing machines used mass production techniques as early as 1846, and the next year, manufacturers mechanized the production of farm machinery.

Innovation was not confined to manufacturing. During the years following the War of 1812, American agriculture underwent a transformation nearly as profound and far reaching as the revolution taking place in industry.

Ironically, it was a shortage of skilled labor that led manufacturers to embrace labor saving machinery and interchangeable parts.

By 1830 the roots of America’s future industrial growth had been firmly planted. Back in 1807, the nation had just fifteen or twenty cotton mills, containing approximately 8,000 spindles. By 1831, the number of spindles in use totaled nearly a million and a quarter. By 1830, Pittsburgh produced 100 steam engines a year; Cincinnati, 150. Factory production had made household manufacture of shoes, clothing, textiles, and farm implement obsolete. The United States was well on its way to becoming one of the world’s leading manufacturing nations.

Changes in Farming Practices

During the eighteenth century, most farm families were largely self-sufficient. They raised their own food, made their own clothes and shoes, and built their own furniture. Cut off from markets by the high cost of transportation, farmers sold only a few items, like whiskey, corn, and hogs, in exchange for such necessities as salt and iron goods. Farming methods were primitive. With the exception of plowing and furrowing, most farmwork was performed by hand. European travelers deplored the backwardness of American farmers, their ignorance of the principles of scientific farming, their lack of labor-saving machinery, and their wastefulness of natural resources. Few farmers applied manure to their fields as fertilizer or practiced crop rotation. As a result, soil erosion and soil exhaustion were commonplace. One observer commented, “Agriculture in the South does not consist so much in cultivating land as in killing it.”

Beginning in the last decade of the eighteenth century, agriculture underwent profound changes. Some farmers began to grow larger crop surpluses and to specialize in cash crops. A growing demand for cotton for England’s textile mills led to the introduction of long staple cotton from the West Indies into the islands and the lowlands of Georgia and South Carolina. Eli Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin in 1793, which permitted an individual to clean 50 pounds of short staple cotton in a single day, 50 times more than could be cleaned by hand, made it practical to produce short staple cotton in the South, which was much more difficult to clean and process than long staple cotton. Other cash crops raised by Southern farmers included rice, sugar, flax for linen, and hemp for rope fibers. In the Northeast, the growth of mill towns and urban centers created a growing demand for hogs, cattle, sheep, corn, wheat, wool, butter, milk, cheese, fruit, vegetables, and hay to feed horses.

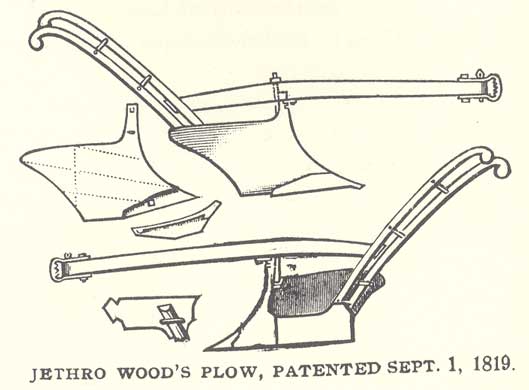

As production for the market increased, farmers began to demand improved farm technology. In 1793 Charles Newbold, a New Jersey farmer, spent his entire fortune of $30,000 developing an efficient cast iron plow. Farmers refused to use it, fearing that iron would poison the soil and cause weeds to grow. Twenty years later, a Scipio, New York, farmer named, Jethro Wood patented an improved iron plow made out of interchangeable parts. Unlike wooden plows, which required two men and four oxen to plow an acre in a day, Wood’s cast iron plow allowed one man and one yoke of oxen to plow the same area. Demand was so great that manufacturers infringed on Wood’s patents and produced thousands of copies of this new plow yearly.

A shortage of farm labor encouraged many farmers to adopt labor-saving machinery. Prior to the introduction in 1803 of the cradle scythe, a rake used to cut and gather up grain and deposit it in even piles, a farmer could not harvest more than half an acre a day. The horse rake a device introduced in 1820 to mow hay allowed a single farmer to perform the work of eight to ten men. The invention in 1836 of a mechanical thresher, used to separate the wheat from the chaff, helped to cut in half the man hours required to produce an acre of wheat.

The Industrial Revolution

To all outward appearances, life in the North in 1790 was not much different than in 1740. The vast majority of the people—more than 90 percent—still lived and worked on farms or in small rural villages. Less than one Northerner in thirteen worked in trade or manufacturing.

Conditions of life remained primitive. The typical house—a single-story one- or two-room log or wood frame structure—was small, sparsely furnished, and afforded little personal privacy. Sleeping, eating, and work spaces were not sharply differentiated, and mirrors, curtains, upholstered chairs, carpets, desks, and bookcases were luxuries enjoyed only by wealthy families.

Even prosperous farming or merchant families lived simply. Many families ate meals out of a common pot or bowl, just as their ancestors had in the seventeenth century. Standards of cleanliness remained exceedingly low. Bedbugs were constant sleeping companions, and people seldom bathed or even washed their clothes or dishes.

Daily life was physically demanding. Most families made their own cloth, clothing, and soap. Because they lacked matches, they lit fires by striking a flint again and again with a steel striker until a spark ignited some tinder. Because there was no indoor plumbing, chamber pots had to be used and emptied. Homes were usually heated by a single open fireplace and illuminated by candles. Housewives hand-carried water from a pump, well, or stream and threw the dirty water or slops out the window. Family members hauled grain to a local grist mill or else milled it by hand. They cut, split, and gathered wood and fed it into a fireplace.

But by 1860, profound and far-reaching changes had taken place. Commercial agriculture had replaced subsistence agriculture. Household production had been supplanted by centralized manufacturing outside the home. And, nonagricultural employment had begun to overtake agricultural employment. Nearly half of the North’s population made a living outside the agricultural sector.

These economic transformations were all results of the industrial revolution, which affected every aspect of life. It raised living standards, transformed the work process, and relocated hundreds of thousands of people across oceans and from rural farms and villages into fast-growing industrial cities.

The most obvious consequence of this revolution was an impressive increase in wealth, per capita income, and commercial, middle-class job opportunities. Between 1800 and 1860, output increased twelve-fold, and purchasing power doubled. New middle-class jobs proliferated. Increasing numbers of men found work as agents, bankers, brokers, clerks, merchants, professionals, and traders.

Living standards rose sharply, at least for the rapidly expanding middle class. Instead of making cloth and clothing at home, families began to buy them. Instead of hand milling grains, an increasing number of families began to buy processed grains. Kerosene lamps replaced candles as a source of light. Coal replaced wood as fuel. Friction matches replaced crude flints. Even poorer families began to cook their food on cast-iron cookstoves and to heat their rooms with individual-room heaters. The advent of railroads and the first canned foods brought year-round variety to the northern diet.

Physical comfort increased markedly. Padded seats, spring mattresses, and pillows became more common. By 1860, many urban middle-class families had central heating, indoor plumbing, and wall-to-wall carpeting.

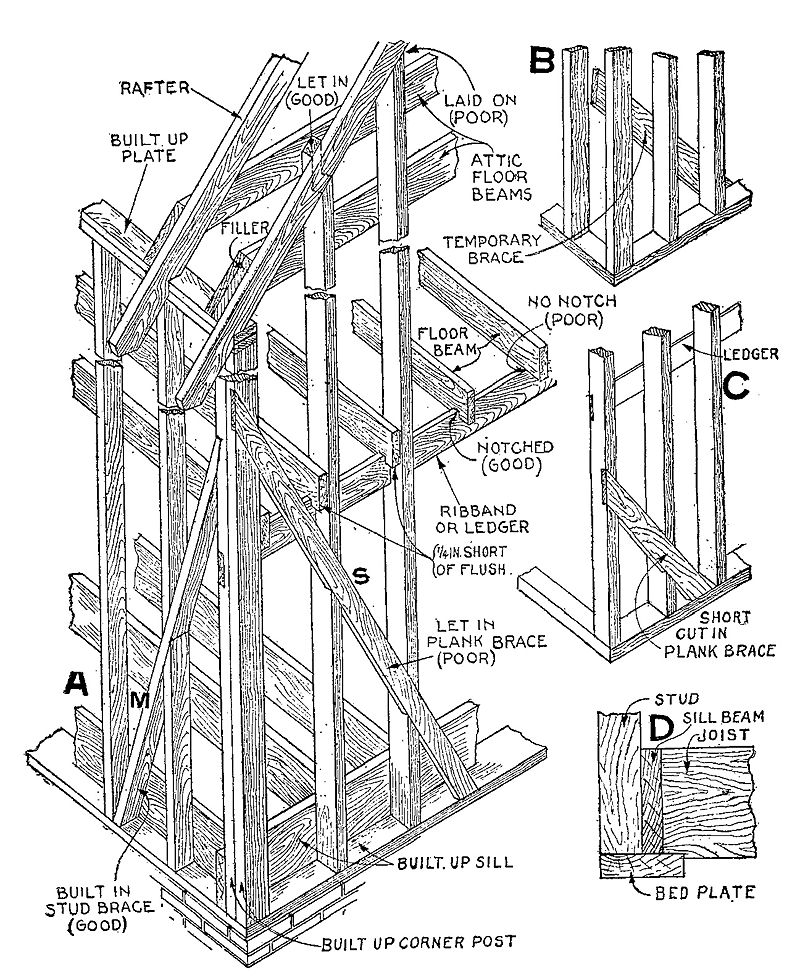

Houses became larger and more affordable. The invention in the 1830s of the balloon frame—a lightweight house frame made up of boards nailed together—as well as prefabricated doors, window frames, shutters, and sashes resulted in larger and more reasonably priced houses. The cost of building a house fell by 40 percent, and two-story houses, with four or five rooms, became increasingly common.

A revolution in values and sensibility accompanied these changes in the standard of living. Standards of cleanliness and personal hygiene rose sharply. People bathed more frequently, washed their clothes more often, and dusted, swept, and scrubbed their houses more regularly. Standards of propriety also rose. The respectable classes began to blow their noses into handkerchiefs, instead of wiping them with their sleeves, and to dispose of their spittle in spittoons.

Northerners regarded all of these changes as signs of progress. A host of Northern political leaders, mainly Whigs and later Republicans, celebrated the North as a region of bustling cities, factories, railroads, and prosperous farms and independent craftsmen—a stark contrast to an impoverished, backward, slave-owning South, suffering from soil exhaustion and economic and social decline.

Although the Industrial Revolution brought many material benefits, critics decried its negative consequences. Labor leaders deplored the bitter suffering of factory and sweatshop workers, the breakdown of craft skills, the vulnerability of urban workers to layoffs and economic crises, and the maldistribution of wealth and property. Conservatives lamented the disintegration of an older household-centered economy in which husbands, wives, and children had labored together. Southern writers, such as George Fitzhugh, argued that the North’s growing class of free laborers were slaves of the marketplace, suffering even more insecurity than the South’s chattel slaves, who were provided for in sickness and old age.

The Industrial Revolution brought prosperity and rising standards of living to some, but severe hardship to others. Purchasing power and productivity increased, but so too did economic inequality. For all its material benefits, the Industrial Revolution was accompanied by regimented work in mills and factories and the recurrent busts that were part of the business cycle. Meanwhile, those at the bottom of the economic order—including day laborers, seamstresses, and servants—suffered from wages near the subsistence level and frequent bouts of unemployment.