Placing U.S. History in Global Perspective

Thinking Comparatively

Placing U.S. History in Global Perspective

The history of the United States is often examined in isolation, separate and apart from the history of other nations. But, this is a mistake. U.S. history is profoundly connected to events outside the country. Also, the history of immigrants, of women, and of ethnic and racial minorities is too often treated as disconnected from the main themes of U.S. history.

The history of the early-nineteenth century provides a particularly vivid example of the interconnections between U.S. history and events abroad and of the links between the history of “outsiders” and the marginalized from the country’s central developments.

There were six great migrations in the early-nineteenth century:

- The movement of millions of European immigrants across the Atlantic, consisting primarily of Irish (52 percent female), German, and Scandinavian immigrants.

- The displacement and forced removal of eastern Indians to the Trans-Mississippi West.

- The migration of thousands of white pioneers to Texas, California, and the Pacific Northwest.

- The forced movement of a million enslaved African Americans and their masters.

- The migration of 500,000 Chinese (five percent female) across the Pacific.

- The movement of tens of thousands of migrants, predominantly native-born white females, from rural areas in the Northeast to booming cities.

All of these migrations—Indian removal, Irish and Chinese migration, the movement of enslaved African Americans into the Deep South, and the movement of native born white women from rural farms to cities and factory towns and pioneers to the Western frontier—were interconnected. Each was a response to profound economic transformations:

- The growth of a market economy, which stimulated demand for factory labor and eliminated the need for young women to spin cloth at home.

- The commercialization of agriculture, which pushed many young women off of their parents’ farms, where their labor was no longer needed.

- A booming demand for cotton by the rapidly expanding textile industry.

- The need to build a network of railroads to transport goods across an increasingly interconnected national economy.

- The expansion of global trade.

For the Irish, the precipitating cause of mass immigration was the Potato Famine, which ravaged Ireland from 1844 to 1854. Although a fungus caused the potato crop, the basic staple of the Irish diet, to rot, there was nothing “natural” about this disaster. The English had restricted population growth and maintained the size of land holdings in a number of ways, including migration, delayed marriage, and primogeniture, bequeathing land only to the eldest son. In contrast, in Ireland, the Irish Catholics owned just ten percent of the land, and tended to subdivide landholdings in order to give each son a plot of land. The result was that landholdings were becoming smaller and smaller.

After the famine struck, British colonial policy worsened the suffering. English landlords evicted subsistence farmers from their farms, and replaced farming with livestock raising. Even during the worst of the famine, landlords continued to export meat from the island.

Many Irish women were rendered economically superfluous. Unlike many other immigrant groups, many Irish women migrated alone. Many became domestic servants; a third became factory workers.

Chinese immigration was intertwined with the desire of business and political interests to acquire California from Mexico in order to develop trade with Asia and then, following the Mexican War, to build a transcontinental railroad to connect California to the eastern United States. Ninety percent of the workers on Central Pacific Railroad were Chinese.

The Mexican War had a profound impact on the Southwest’s Mexican population. Most were reduced to second class citizenship and lost control of land as a result of onerous taxes and the difficulty of proving their land claims. Many Mexicans would subsequently become migratory laborers, working on farms and ranches or in mines or on railroads.

Hidden History

Forgotten History: The United States and China

Karl E. Meyer, “The Opium War’s Secret History” New York Times, June 28, 1997

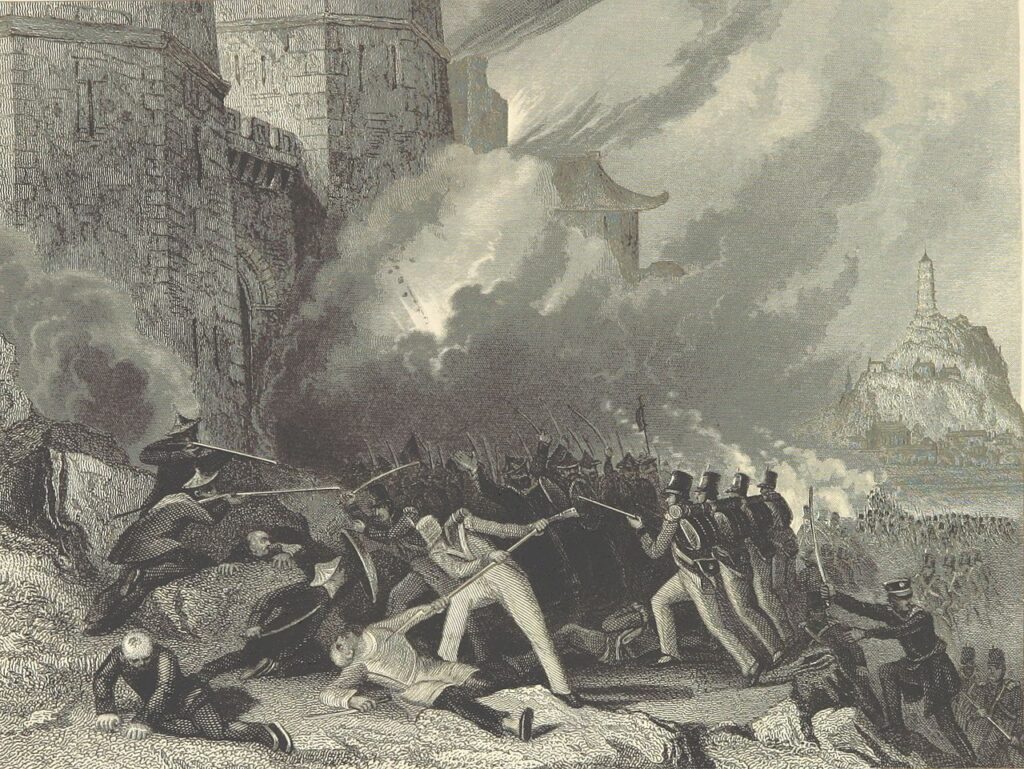

Losers rarely name wars, an exception being the conflict between Britain and China from 1839 to 1842, known bluntly ever since as the Opium War. To most Chinese, a century of humiliation began with this war, in which Westerners sought to force a deadly drug on an Asian people, and then imposed an unequal treaty that pried open their country and annexed the island that became Hong Kong…

Along with the slave trade, the traffic in opium was the dirty underside of an evolving global trading economy. In America as in Europe, pretty much everything was deemed fair in the pursuit of profits. Such was the outlook at Russell & Company, a Boston concern whose clipper ships made it the leader in the lucrative American trade in Chinese tea and silk.

In 1823 a 24-year-old Yankee, Warren Delano, sailed to Canton, where he did so well that within seven years he was a senior partner in Russell & Company. Delano’s problem, as with all traders, European and American, was that China had much to sell but declined to buy. The Manchu emperors believed that the Middle Kingdom already possessed everything worth having, and hence needed no barbarian manufactures.

The British struck upon an ingenious way to reduce a huge trade deficit. Their merchants bribed Chinese officials to allow entry of chests of opium from British-ruled India. They acquired the “black dirt” in Turkey or India.

As addiction became epidemic, and as the Chinese began paying with precious silver for the drug, their Emperor tried to end the trade.

Vast stocks of opium were seized and dumped into the sea. This furnished the pretext for the Opium War. China was humbled, forced to open five ports to foreign traders and to permit a British colony at Hong Kong. Perhaps as noteworthy, the war was denounced by pulpit and press.

Warren Delano returned to America rich, and in 1851 settled in Newburgh, New York. There, he eventually gave his daughter Sara in marriage to a well-born neighbor, James Roosevelt, the father of Franklin Roosevelt.