Introduction: Social and Economic Change in Pre-Civil War America

When Did Human Life Change Most?

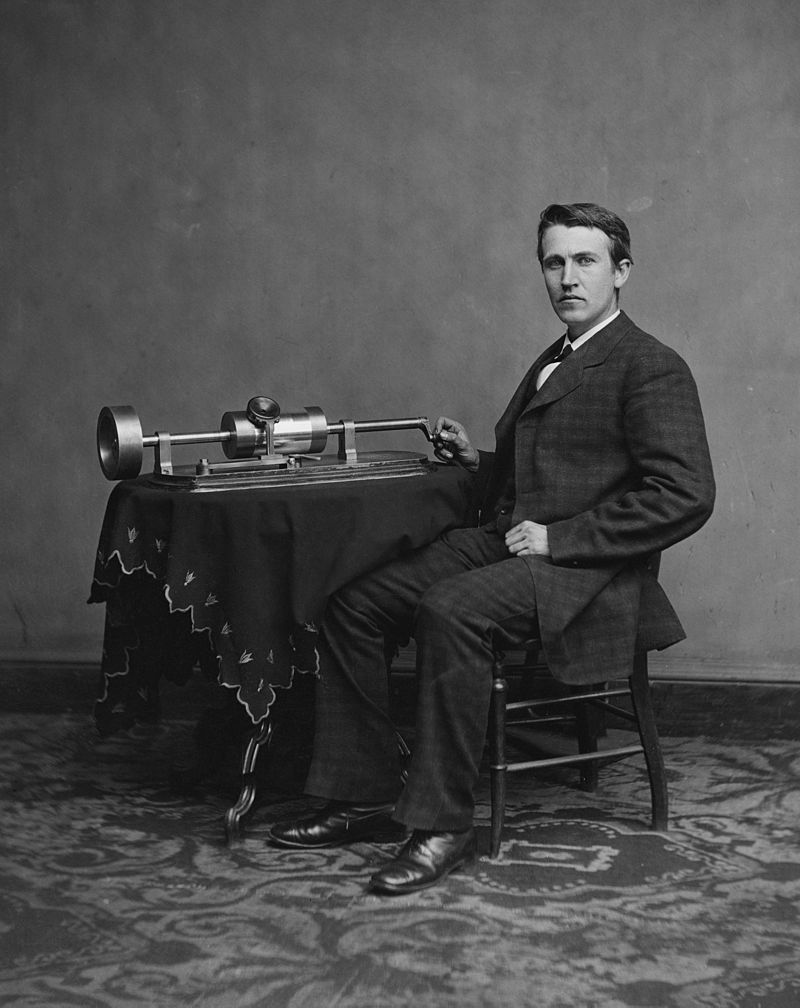

Was it in the 1870s, when Thomas Edison introduced the electric light and the phonograph, Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone, and Karl Benz demonstrated the first workable internal combustion engine?

The first decade of the twentieth century, which saw the introduction of the airplane, the first synthetic plastics, and the first radio broadcast?

The 1970s, with the first microprocessor, videogame, microcomputer, email, the video cassette recorder, and the internet?

A case can be made that the biggest changes occurred during the 1830s. During that decade, the railroad, good interior lighting, running water, central heating, cook stoves, iceboxes, the telegraph, and mass-circulation newspapers all became commonplace.

American Life in the Early Nineteenth Century

In 1800, the American population was exceedingly small. The population was just over five million at a time that England had fifteen million inhabitants and France twenty-seven million. Half the U.S. population was under the age of sixteen and twenty percent of the population was enslaved. All told, there were probably just over half a million free, able-bodied adult white males.

After two centuries of settlement, the land remained largely untamed. Two-thirds of the population lived within fifty miles of the Atlantic coast and the center of the population was just eighteen miles west of Baltimore. Buffalo, Rochester, and Utica in western New York were still part of Indian county. Meanwhile, Wisconsin, Michigan, Illinois, and Indiana belonged to the Wyandottes, Shawnees, Miamis, and Kickapoo. In the South, Mississippi and Alabama, belonged to the Creek, Cherokees, Chicasaws, and Choctaws. The entire American population west of the Appalachian and Allegheny mountains amounted to less than half a million.

Ninety percent of the population in the Northeast and ninety-five percent of the people of the South lived on farms or in villages with fewer than 2,500 inhabitants.

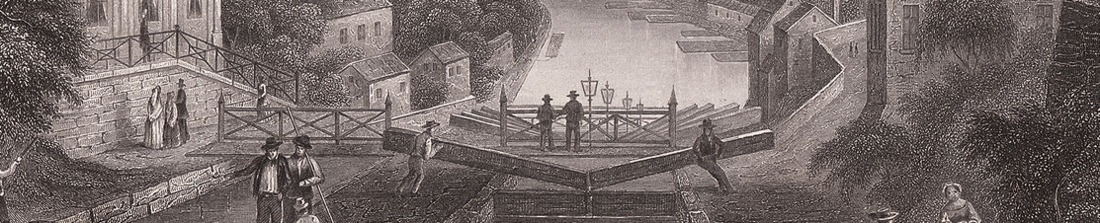

Transportation in 1800 was scarcely any better than in 1700. The movement of people and goods still depended on horses, boats, wagons, and stagecoaches, with the passengers protected from the heat or cold only by leather flaps buttoned to the roof and sides. In New England, travel was forbidden on the Sabbath. It took three days to travel the 215 miles from Boston to New York and another two days to get from New York to Philadelphia, a distance of less than 100 miles. When President Jefferson traveled between Washington and his home at Monticello, he had to cross eight rivers. Five had neither bridges nor boats. It took twenty days to deliver a letter between Maine and Georgia.

By later standards, life was primitive. Fifty miles inland, at least half of the houses were log cabins, lacking even glass windows. Bathrooms were still unknown, and churches were unheated. Most clothing was cut and made at home.

Outside of political thought, intellectual life struck many as undeveloped. All the public libraries in the new nation contained only about 50,000 volumes, including duplicates.

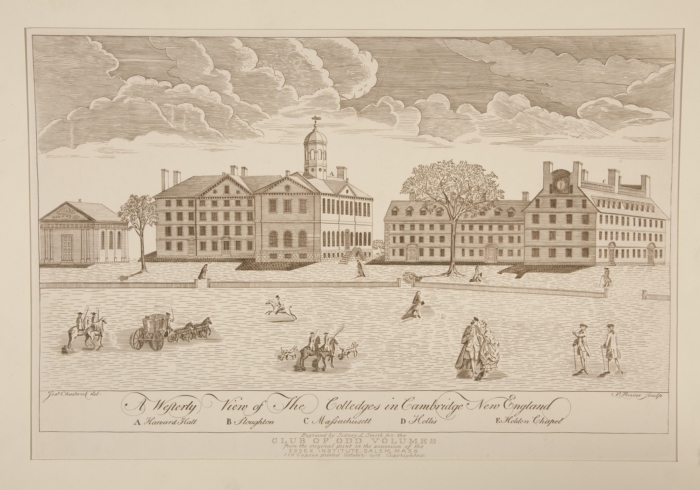

Nor were there any marked improvements in higher education. There were just twenty-two colleges in the United States. The most prestigious, Harvard, graduated just thirty-nine students a year, no more than in 1700. Its students typically entered at the age of fourteen, and its entire faculty consisted of a president, a professor of theology, a professor of mathematics, and a professor of Hebrew, along with the four tutors.

Methods of production were little changed from a century earlier. Farmers’ plows were still made of wood and manufacturing was very small in scale. There were only two or three small cotton mills. In 1803, no more than five steam engines in the entire country. The leading manufacturing industries, iron making, textiles, and clothes making, employed only about 15,000 people in mills or factories.

The four largest cities—Baltimore, Boston, New York, and Philadelphia—had a combined population of only about 180,000, and were the only cities with more than 10,000 inhabitants. As for the nation’s new capital, Washington, D.C., members of Congress resided in between eight and ten boarding houses. The city lacked shops or markets.

President Jefferson himself was unsure whether the United States would remain a single unified nation. “Whether we remain in one confederacy,” he wrote in 1804, “or form into Atlantic and Mississippi confederations, I believe not very important to the happiness of either part.”

Resistance to change was strong. “Let us guard against the insidious encroachments of innovation,” a Boston minister and Yale graduate) named Jedidiah Morse preached, “that evil and beguiling spirit which is now stalking to and fro through the earth, seeking whom he may destroy.”

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the nation’s future economic prospects seemed bleak. And yet in the space of just three decades, the United States became a world leader in industry. The country stood on the verge of extraordinary transformations.