The Economics of Slavery

History Through…

Material Conditions of Slave Life

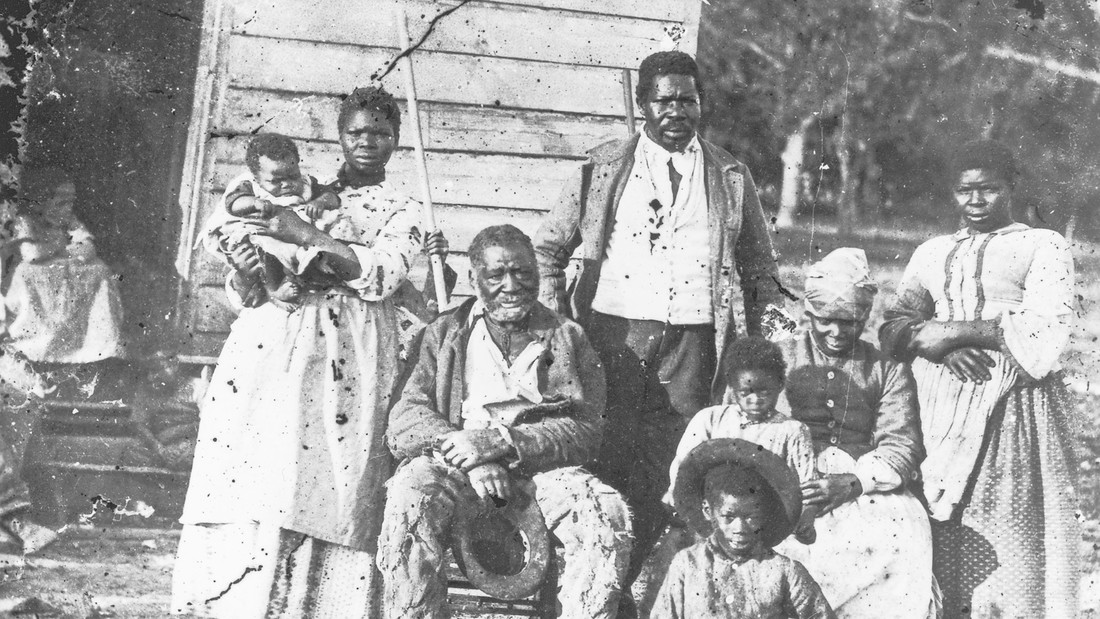

Deprivation and physical hardship were the hallmarks of life under slavery. Plantation records reveal that over half of all slave babies died during their first year of life, a rate twice that of white babies. Although slave children’s death rate declined after the first year of life, it remained twice the white rate.

The average slave’s small size indicates a deficient diet. At birth, over half of all slave children weighed less than five pounds, or what today is considered to be severely underweight. Throughout their childhoods, slaves were smaller than white children of the same age. The average slave children did not reach three feet in height until their fourth birthdays, which is five inches shorter than a typical child today. At age seventeen, slave men were shorter than ninety-six percent of present day American men, and slave women were smaller than eighty percent of American women.

The slaves’ diet was monotonous and unvaried, consisting largely of corn meal, salt pork, and bacon. Only rarely did slaves drink milk or eat fresh meat or vegetables. This diet provided enough bulk calories to ensure that slaves had sufficient strength and energy to work as productive field hands, but it did not provide adequate nutrition. As a result, slaves frequently suffered from vitamin and protein deficiencies, and were victims of aliments such as beriberi, kwashiorkor, and pellagra. Poor nutrition and high rates of infant and child mortality contributed to a short average life expectancy of twenty-one or twenty-two years compared to forty to forty-three years for whites.

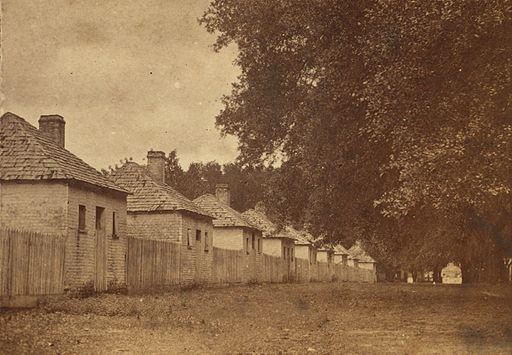

The physical conditions in which slaves lived were appalling. Lacking privies, slaves had to urinate and defecate in the cover of nearby bushes. Lacking any sanitary disposal of garbage, they were surrounded by decaying food. Chickens, dogs, and pigs lived next to the slave quarters, and in consequence, animal feces contaminated the area. Such squalor contributed to high rates of dysentery, typhus, diarrhea, hepatitis, typhoid fever, and intestinal worms.

Slave quarters were cramped and crowded. The typical cabin, a single, windowless room, with a chimney constructed of clay and twigs and a floor made up of dirt or planks resting on the ground ranged in size from ten by ten feet to twenty-one by twenty-one feet. These small cabins were often quite crowded, containing five, six, or more occupants. On some plantations, slaves lived in single-family cabins. On others, two or more shared the same room. On the largest plantations, unmarried men and women were sometimes lodged together in barracks like structures. Josiah Henson, the Kentucky slave who served as the model for Harriet Beecher Stowe’s, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, described his plantation’s cabins this way:

We lodged in log huts…Wooden floors were an unknown luxury. In a single room were huddled, like cattle, ten or a dozen persons, men, women, and children…There were neither bedsteads nor furniture…Our beds were collections of straw and old rags…The wind whistled and the rain and snow blew in through the cracks, and the damp earth soaked in the moisture till the floor was muddy as a pig sty.

History Through…

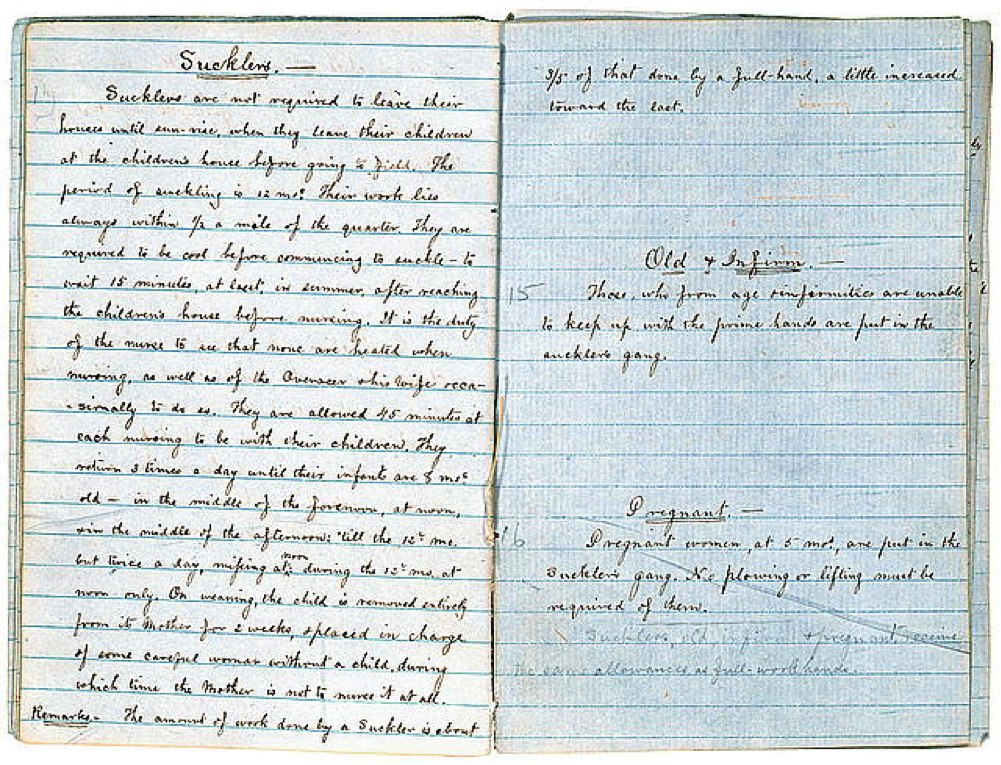

…A Plantation Manual

This page from the plantation manual of U.S. Senator James Henry Hammond of South Carolina offers detailed instructions to overseers about how they are to treat nursing mothers. It also specifies work arrangements for the elderly and for pregnant slaves. Hammond, who warned the North against threatening the South—declaring “You dare not make war on cotton—no power on earth dares make war upon it. Cotton is king.”—not only took a slave woman, and later her daughter, as his mistress, but also records in his diary having relations with four adolescent nieces.

Sucklers [nursing mothers].—

Sucklers are not required to leave their houses until sun-rise, when they leave their children at the children’s house before going to field. The period of suckling is 12 mo[nths]: Their work always lies within ½ a mile of the quarter. They are required to be cool before commencing to suckle—to wait 15 minutes, at least, in summer, after reaching the children’s house before nursing. It is the duty of the nurse to see that none are heated when nursing, as well as of the Overseer & his wife occasionally to do so. They are allowed 45 minutes at each nursing to be with their children. They return 3 times a day until their infants are 8 mo[nth]s old – in the middle of the forenoon, at noon, in the middle of the afternoon: ‘till the 12 mo[nth] but twice a day, missing at noon: during the 12 mo[nth] at noon only. On weaning, the child is removed entirely from its mother for 2 weeks, & placed in charge of some careful woman without a child, during which time the mother is not to nurse it at all.

Remarks.—

The amount of work done by a Suckler is about 3/5s of that done by a full hand, a little increased toward the last.

Old & Infirm.—

Those, who from age infirmities are unable to keep up with the prime hands are put in the suckler’s gang.

Pregnant.—

Pregnant women, at 5 mo[nths], are put in the suckler’s gang. No plowing or lifting must be done of them.

The Economics of Slavery

During the years before the Civil War, a growing number of Northerners associated slavery with economic backwardness, soil exhaustion, low labor productivity, indebtedness, and economic and social stagnation. Philosopher and poet, Ralph Waldo Emerson, said that “slavery is no scholar, no improver…it does not increase the white population; it does not improve the soil; everything goes to decay.” Many Northerners charged that slavery was incompatible with rapid economic growth.

Like other slave societies, the South did not produce urban centers on a scale equal with those in the North. Virginia’s largest city, Richmond, had a population of just 15,274 in 1850. Southern cities were small because they failed to develop diversified economies. Unlike the cities of the North, southern cities rarely became centers of commerce, finance or processing and manufacturing and southern ports rarely engaged in international trade.

By Northern standards, the South’s transportation network was primitive. Traveling the 1,460 miles from Baltimore to New Orleans in 1850 meant riding five different railroads, two stage coaches, and two steamboats. Its educational system also lagged far behind the North’s. In 1850, twenty percent of adult white southerners could not read or write, compared to a national figure of eight percent.

Does this mean that slavery was doomed to extinction, even in the absence of Civil War? The answer appears to be “no.” In 1860, the South was more prosperous than any European nation except England, and it had a higher per capita income than Italy on the eve of World War II.

Slave labor was efficient, productive, and adaptable to a variety of occupations, ranging from agriculture and mining to factory work. Slavery was the basis of the nation’s most profitable industry, the manufacture of textiles. During the decades before the Civil War, slave-grown cotton accounted for over half the value of all United States exports. Furthermore, a disproportionate share of the richest Americans made their fortunes from slavery. In 1860, two out of every three Americans worth $100,000 or more lived in the South. Slave prices soared during the 1850s, an indication of slave owners’ confidence in the future.

Nevertheless, the South’s political leaders had good reason for concern. Within the South, slave ownership was becoming concentrated into a smaller number of hands. The proportion of southern families owning slaves declined from 36 percent in 1830 to 25 percent in 1860. At the same time, slavery was sharply declining in the upper South. Between 1830 and 1860, the proportion of slaves in Missouri’s population fell from 18 to 10 percent, in Kentucky, from 24 to 19 percent, in Maryland, from 23 to 13 percent. But the most important threat to slavery came from abolitionists, who denounced slavery as immoral.