Slave Family Life and Cultural Resistance

Slave Family Life and Cultural Resistance

In 1858, after being sold away from his family, a Georgia slave named Abream Scriven wrote the following words to his wife: “Give my love to my dear father and mother and tell them good bye for me…My dear wife for you and all my children my pen cannot express the grief I feel to be parted from you. I remain your true husband until death.”

Slavery severely strained family life. Sale, debt, or an owner’s death could lead to family separation. During the Civil War, nearly twenty percent of ex-slaves reported that an earlier marriage had been terminated by sale.

Meanwhile, half of all slave children lived apart from their father, because he lived on another plantation, had been sold, or was white and refused to recognize his offspring. Between the ages of seven and ten, children were frequently taken from their parents and sent to live in separate cabins. During adolescence, about half of all slaves were sold away from their families. And yet, despite the constant threat of sale and family breakup, African Americans managed to forge strong familial ties. Nuclear family ties stretched outward to an involved network of extended kin.

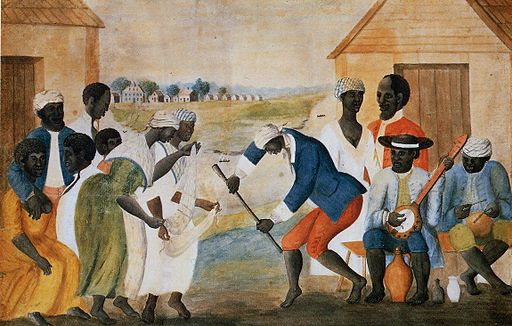

Through their families, religion, folklore, and music, as well as more direct forms of resistance, African Americans resisted the debilitating effects of slavery and created a vital culture supportive of human dignity. Slaves succeeded in maintaining a great deal of their African traditions and created a new African American culture that they successfully transmitted to their children and which exerted a profound influence on all aspects of American culture.

The American language is filled with Africanisms. Such words as bogus, bug, phony, yam, tote, gumbo, jaboree, jazz, and funky all have African roots. Our cuisine, too, is heavily influenced by African practices. Deep-fat frying, gumbos, and fricasees stem from West and Central Africa. Our music is heavily dependent on African traditions.

Sea chanties and yodeling, as well as spirituals and the use of falsetto were heavily influenced by African traditions. The frame construction of houses; the “call and response” pattern in sermons; the stress on the holy spirit and an emotional conversion experience—these too appear to derive at least partly from African customs.

Finally, Africans played a critical role in the production of crops, such as rice and sweet potatoes that English had not previously encountered. In the realms of art, dance, folklore, language, music, and religion, slaves created a distinctive culture, which blended African and European elements into a new synthesis.

A major form of black religious expression was the spiritual. Slave spirituals, like “Go Down Moses” with its refrain “let my people go,” indicated that slaves identified with the history of the Hebrew people, who had been oppressed and enslaved, but achieved eventual deliverance.

Folklore provided another major form of slave cultural expression. Slave folktales were much more than amusing stories. Slaves used them to comment on the whites around them and to convey everyday lessons for living. Among the most popular slave folktales were animal trickster stories, like the Brer Rabbit tales, derived from similar African stories, which told of powerless creatures who achieve their will through wit and guile rather than power and authority. These tales taught slave children how they had to function in a white dominated world and held out the promise that the powerless would eventually triumph over the strong.

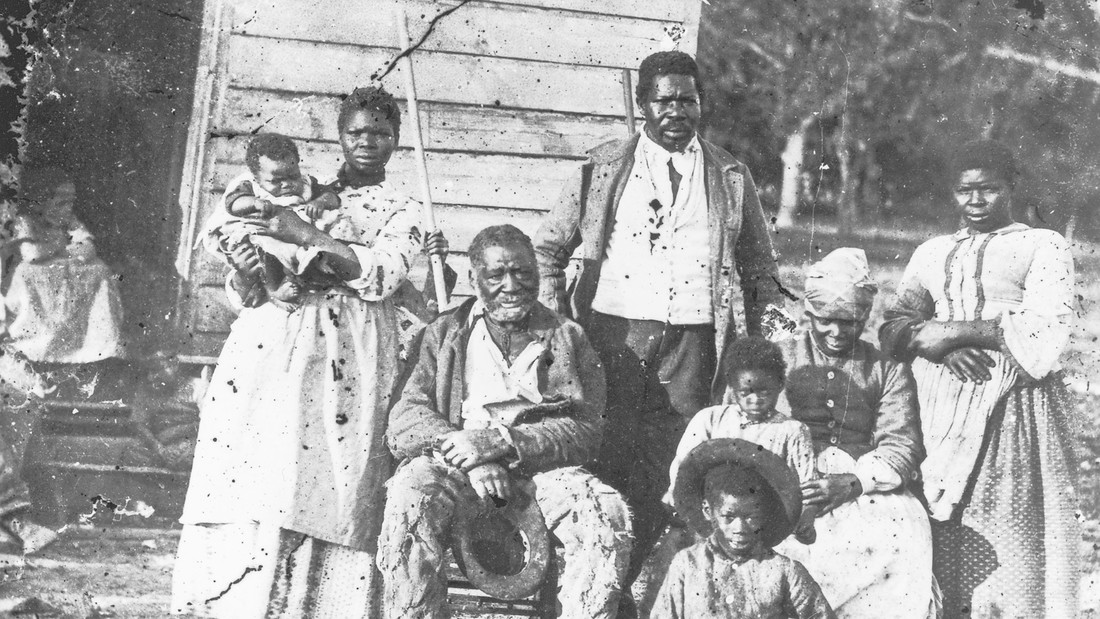

“Five Generations of a Slave Family”

Despite sale and family separation, enslaved African Americans succeeded in maintaining strong familial and kinship ties. Even though slave marriages lacked legal sanction, these unions proved to be durable and slave parents and children received support from an network of kin and non-kin.

Nevertheless, slavery imposed harsh pressures on family life. As many as half of all slave children grew up apart from their father, either because he resided on another plantation or because he was white. During their teens or early twenties, a majority of slave adolescents were sold apart from their families. It is notable that this photograph does not portray a single young adult male.

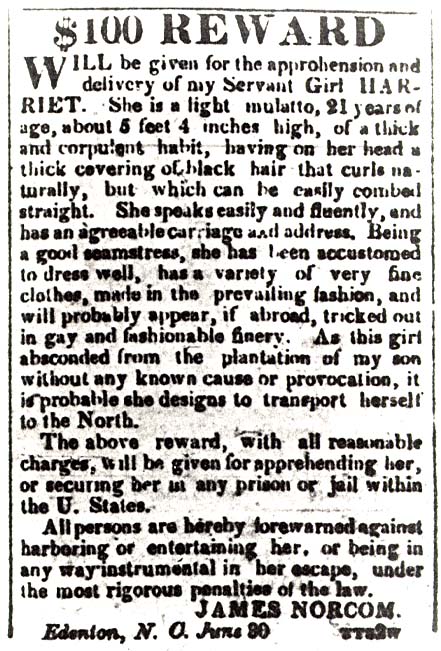

Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Boston, 1861

Women’s experience under slavery differed in significant ways from that of free women and of enslaved men and that the strategies that women adopted to resist slavery were different from male slaves’. At a time when an emerging urban middle class upheld a gender ideal in which married women were not to engage in labor outside the home, enslaved women were involved in many different kinds of work: as field hands, domestic servants, and active participants in local markets. Slave women played a prominent role not only domestic service and cooking, making and mending clothes, and tending garden plots, but in rice cultivation, textile manufacture, and various forms of handicrafts. Enslaved women also dominated marketing of foodstuffs and items manufactured by slaves.

Enslaved women played crucial roles within slave families and within the broader slave community, transmitting knowledge about healing, serving as midwives during childbirth, and overseeing courtship. Not only were they primarily responsible for the day-to-day care of infants and children, enslaved women played active roles in religion, health care, and the transmission of cultural legacies, values, and practical knowledge to children.

“Slavery is terrible for men, but it is far more terrible for women,” Harriet Jacobs wrote in 1861, under the pen name Linda Brent. Jacobs was the author of the most widely read woman’s slave narrative, the thinly veiled autobiographical Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. “I have not exaggerated the wrongs inflicted by slavery…” Jacobs told her readers. “Only by experience can anyone realize how deep, and dark, and foul is that pit of abominations.”

Born into slavery in rural North Carolina in 1813, she was sent, following her mistress’s death, to live with a cruel and abusive doctor, James Norcom. Refusing to submit to his sexual advances, fifteen-year-old Jacobs sought protection by beginning a sexual relationship with an unmarried white neighbor, Samuel Tredwell Sawyer (who later became a member of Congress), with whom she had two children. She asks her readers to refuse to judge her harshly, and to realize how few options she had.

To escape the doctor’s persistent threats and verbal and physical abuse, Jacobs hid in a cramped attic in her grandmother’s shed, nine feet long, seven feet wide, and just three feet high at its tallest point. She spent much of her time for nearly seven years in this cramped, uninsulated space, peering through cracks in the walls to catch a glimpse of her children.

In 1842, Jacobs was smuggled to Philadelphia aboard a schooner, and supported herself as a nursemaid. Ten years later, her employer purchased her freedom for $300, provoking deep ambivalence, since Jacobs never wanted to see herself as owned by another person. “I am deeply grateful to the generous friend who procured [my freedom],” she wrote, “but I despise the miscreant who demanded payment for what never rightfully belonged to him or his.”

During the Civil War, Jacobs raised money from Quakers and women’s rights activists, and used the funds to provide clothing, blankets, and other supplies for ex-slaves who fled to contraband camps behind Union lines. She worked as a seamstress, cook, boarding house operator, and founder of a school for African Americans.

A small shed had been added to my grandmother’s house years ago. Some boards were laid across the joists at the top, and between these boards and the roof was a very small garret, never occupied by any thing but rats and mice. It was a pent roof, covered with nothing but shingles, according to the southern custom for such buildings. The garret was only nine feet long and seven wide. The highest part was three feet high, and sloped down abruptly to the loose board floor. There was no admission for either light or air. My uncle Philip, who was a carpenter, had very skilfully made a concealed trap-door, which communicated with the storeroom. He had been doing this while I was waiting in the swamp. The storeroom opened upon a piazza. To this hole I was conveyed as soon as I entered the house. The air was stifling; the darkness total. A bed had been spread on the floor. I could sleep quite comfortably on one side; but the slope was so sudden that I could not turn on the other without hitting the room. The rats and mice ran over my bed; but I was weary, and I slept such sleep as the wretched may, when a tempest has passed over them. Morning came. I knew it only by the noises I heard; for in my small den day and night were all the same. I suffered for air even more than for light. But I was not comfortless. I heard the voices of my children. There was joy and there was sadness in the sound. It made my tears flow. How I longed to speak to them! I was eager to look on their faces; but there was no hole, no crack, through which I could peep. This continued darkness was oppressive. It seemed horrible to sit or lie in a cramped position day after day, without one gleam of light. Yet I would have chosen this, rather than my lot as a slave, though white people considered it an easy one; and it was so compared with the fate of others. I was never cruelly overworked; I was never lacerated with the whip from head to foot; I was never so beaten and bruised that I could not turn from one side to the other; I never had my heel-strings cut to prevent my running away; I was never chained to a log and forced to drag it about, while I toiled in the fields from morning till night; I was never branded with hot iron, or torn by bloodhounds. On the contrary, I had always been kindly treated, and tenderly cared for, until I came into the hands of Dr. Flint. I had never wished for freedom till then. But though my life in slavery was comparatively devoid of hardships, God pity the woman who is compelled to lead such a life!

My food was passed up to me through the trap-door my uncle had contrived; and my grandmother, my uncle Phillip, and aunt Nancy would seize such opportunities as they could, to mount up there and chat with me at the opening. But of course this was not safe in the daytime. It must all be done in darkness. It was impossible for me to move in an erect position, but I crawled about my den for exercise. One day I hit my head against something, and found it was a gimlet. My uncle had left it sticking there when he made the trap-door. I was as rejoiced as Robinson Crusoe could have been at finding such a treasure. It put a lucky thought into my head. I said to myself, “Now I will have some light. Now I will see my children. ” I did not dare to begin my work during the daytime, for fear of attracting attention. But I groped round; and having found the side next the street, where I could frequently see my children, I stuck the gimlet in and waited for evening, I bored three rows of holes, one above another; then I bored out the interstices between. I thus succeeded in making one hole about an inch long and an inch broad. I sat by it till late into the night, to enjoy the little whiff of air that floated in. In the morning I watched for my children. The first person I saw in the street was Dr. Flint. I had a shuddering, superstitious feeling that it was a bad omen. Several familiar faces passed by. At last I heard the merry laugh of children, and presently two sweet little faces were looking up at me, as though they knew I was there, and were conscious of the joy they imparted. How I longed to tell them I was there!

Slave Resistance

Although slave masters described their slave population as faithful, docile, and contented, slave owners always feared slave revolt. One historian has identified over 200 examples of open rebellion or fears of slave conspiracies in America between the early seventeenth and the mid-nineteenth centuries.

African Americans resisted slavery in a variety of active and passive ways. “Day-to-day resistance” was the most common form of opposition to slavery. Breaking tools, feigning illness, staging slowdowns, and committing acts of arson and sabotage—all were forms of resistance and expressions of slaves’ alienation from their masters.

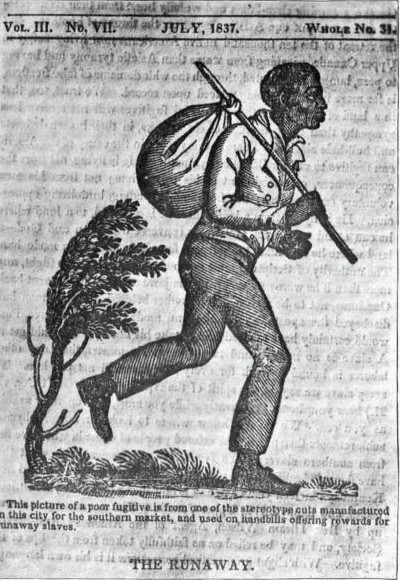

Running away was another form of resistance. Most slaves ran away relatively short distances and were not trying to permanently escape from slavery. Instead, they were temporarily withholding their labor as a form of economic bargaining and negotiation. Slavery involved a constant process of negotiation as slaves bargained over the pace of work, the amount of free time they would enjoy, monetary rewards, access to garden plots, and the freedom to practice burials, marriages, and religious ceremonies free from white oversight.

Some fugitives did try to permanently escape slavery. While the idea of escaping slavery quickly brings to mind the Underground Railroad to the free states, in fact more than half of these long-distance runaways headed southward or to cities or to natural refuges like swamps. Often, runaways were relatively privileged slaves who had served as river boatmen or coachmen and were familiar with the outside world.

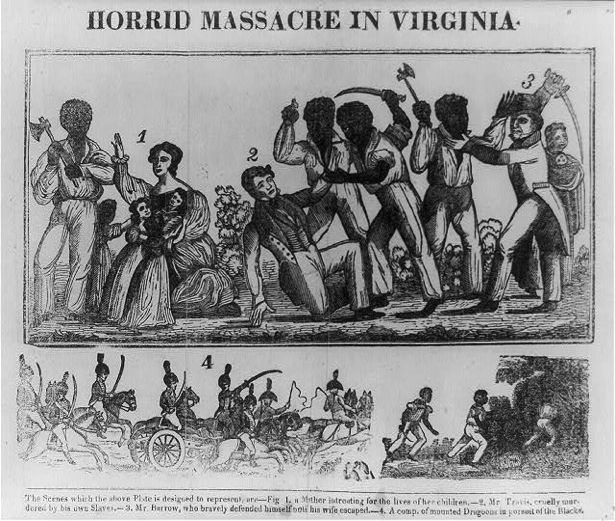

Over the course of American history, there were a number of large-scale physical revolts. During the early-eighteenth century, there were slave uprisings in Long Island in 1708 and in New York City in 1712. Slaves in South Carolina staged several insurrections, culminating in the Stono Rebellion in 1739, when they seized arms, killed whites, and burned houses. In 1740 and 1741, conspiracies were uncovered in Charleston and New York. During the 1820s, a fugitive slave named Bob Ferebee led a band in fugitive slaves in guerrilla warfare in Virginia. During the early nineteenth century, major conspiracies or revolts against slavery took place in Richmond, Virginia, in 1800, in Louisiana in 1811, in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1822, and in Southampton County, Virginia in 1831.

Slave revolts were most likely when slaves outnumbered whites, when masters were absent, and during periods of economic distress. They were also most common in areas with the largest plantations, at times when the white elite was divided, and when large numbers of native-born Africans had been brought into an area at one time.

Black religion made a major contribution to resistance to slavery. When Denmark Vesey sought to gain recruits for his plot to overthrow slavery in Charleston in 1822, one slave said, “he tries to prove…that slavery and bondage is against the Bible.” Nat Turner’s 1831 insurrection was inspired by a religious vision that revealed that “the time was fast approaching when the first should be last and the last should be first.”

The main result of slave insurrections, however, was the mass executions of blacks. After a slave conspiracy was uncovered in New York City in 1741, eighteen slaves were hanged and thirteen were burned alive. After Denmark Vesey’s conspiracy was uncovered, the authorities in Charleston hanged thirty-seven blacks. Following Nat Turner’s insurrection, the local militia killed about 100 blacks and twenty more slaves, including Turner, were later executed. In the South, the preconditions for successful rebellion did not exist, and tended to bring increased suffering and repression to the slave community.

Violent rebellion was rarer and smaller in scale in the American South than in Brazil or the Caribbean, reflecting the relatively small proportion of blacks in the Southern population, the low proportion of recent migrants from Africa, and the relatively small size of southern plantations. Compared to the Caribbean, prospects for successful sustained rebellions in the American South were bleak. In Jamaica, slaves outnumbered whites by ten or eleven to one. In the South, a much larger white population was committed to suppressing rebellion. In general, Africans were more likely than New World born slaves to participate in outright revolts. Not only did many Africans have combat experience prior to enslavement, but also had fewer family and communities ties that might inhibit violent insurrection.

Sight and Sound

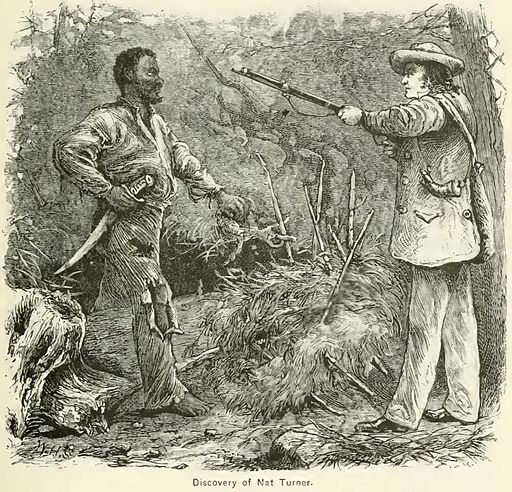

Nat Turner’s Insurrection

Although Nat Turner’s revolt was far smaller in scale than insurrections that took place in Haiti, Jamaica, and Demerara, it exerted an immense impact on American society. The uprising, which involved from 60 to 80 slaves and left about 60 whites dead, touched off panics in many parts of the South, which resulted in the killings of scores of blacks. The revolt led some state legislatures to make it a crime to teach slaves to read or write, and the Virginia legislature actually debated whether slavery should continue to be legal in the state. Because the revolt took place just eight months after William Lloyd Garrison’s militant antislavery newspaper, The Liberator, appeared, many white Southerners blamed the abolitionist movement for somehow contributing to the insurrection. Meanwhile, abolitionists noted that the insurrection utterly disproved the contention of slavery apologists that slaves were contented.

History Through…

…Fugitive Slaves Advertisements

Colonial newspapers frequently contained announcements of slave sales and requests for overseers as well as ads for runaway slaves. These advertisements, though brief in length, are filled with valuable information.

Advertisement 1

Printed in: | Savannah, Georgia | July 25, 1774

RUN AWAY at the 20th or May last from John Forbes, Esq’s plantation in St. John’s parish, TWO NEGROES, named BILLY and QUAMINA of the Guinea Country, and speak good English. Billy is lusty and well built, about 5 feet 10 or 11 inches high, of a black complection [complexion], has lost some of his upper teeth, and had on when he went away a white negroe cloth jacket and trowsers [trousers] of the same. Quamina is stout and well made, about 5 feet 10 or 11 inches high, very black. Has his country marks on his face, had on when he went away a jacket, trowsers, and rabbin [ribbon?] of white negroe cloth. Whoever takes up said Negroes, and deliver them to me at the above plantation, or to the Warden of the Work-House in Savan , shall receive a reward of 20 s[hillings], besides what the law allows.

By: Davis Austin

Advertisement 2

Printed in: Virginia Gazette (Hunter) | Williamsburg | February 28, 1755

RAN away from Brandon, in Prince-George County, on the 9th of December last, a Negroe Man Slave, named Cain, belonging to Col. Nathaniel Harrison, formerly his Coachman; he is a tall, black, elderly, smooth-tongued Fellow: It is suppos’d that he has followed a Negroe Woman belonging to Major Thomas Hall (which he used to visit as a Wife) to North-Carolina; but as he was well acquainted in many Parts of the Country, he may be gone elsewhere: He took with him a dark-grey Mare, low in Flesh, paces well, and branded on the Buttock and Shoulder, but can’t remember the Brand, also a Country-made Saddle with Leather Housing, a Pair of Shoe-Boots, a long dark color ‘d riding Coat, a new white Plains Jacket and Breeches, Oznabrig Shirts, and Plenty of other Apparel. Whoever will convey him to Brandon, if taken up out of the Colony, shall have Two Pistoles Reward, besides what the Law allows, or otherwise One Pistole, to be paid by William Skipwith

By: William Skipwith

Advertisement 3

Printed in: Virginia Gazette (Dixon & Nicholson) | Richmond | August 23, 1780

ONE THOUSAND DOLLARS REWARD. RUN away from the subscriber living at Charlotte court-house; Daniel, a stout black fellow, about 25 years of age, 5 feet 9 or 10 inches high, has a small scar on his upper lip, and one on his breast, has a flat foot, large ancles, and several gray hairs in his head; had on when he went away, a cotton shirt, a pair of leather breeches, a jump jacket, and red bath coating coat; he carried other wearing apparel; he was some time ago purchased to Josiah Hunley of Amelia, and formerly belonged to Mr. Dickerson of York county. As he is a very artful fellow, I expect he will endeavour to pass for a freeman and get on board some vessel. All masters of vessels and others, are forwarned from harbouring the said slave, or conveying him out of the state. As he has relations about Williamsburg, I have reason to believe that he is lurking about in that neighnourhood. I will pay the above reward to any person who shall secure the said slave, so that I get him again, and if brought home reasonable charges paid.

By: Robert Rakestraw

Advertisement 4

Printed in: Virginia Gazette (Hunter) | Williamsburg | October 27, 1752

RAN away from the Subscriber, living in New-Kent County, on the first day of September last, a fair Mulatto Woman Slave, named Moll, about 22 Years of Age, and 5 Feet high, with brown Hair, grey Eyes, very large Breasts and Limbs two of her upper fore Teeth are rotten and broken off; she took with her 4 brown Linnen Shirts, 3 Virginia-Cloth Petticoats, 3 Roles Aprons, several Holland Caps, and an old blue and white Virginia-Cloth Wastecoat; she stole about Five Pounds in Cash, so that its likely she may have bought other Cloathes, she is a very sly subtle Wench and a great Lyar; she is very handy about waiting and tending in a House, and can wash, iron and sew coarse Work: It’s likely she may change her Name, pass for a free Woman and hire herself. Whoever will bring her to Col. William Macon, in New-Kent County, to Mr. William Macon, Jun. in Hanover County, or to the Subscriber, shall have Two Pistoles Reward, besides what the Law allows.

By: Martha Massie

Advertisement 5

Printed in: Virginia Gazette (Rind) | Williamsburg | October 26, 1769

RAN away from the subscriber, living near Petersburg, about the first of May last, a likely Negro woman of a yellow complexion, about 30 years of age, had when she went away silver buckles, and change of apparel, which makes her appear more like a free woman; she carried with her a male child about two years old, and I hear there is a Mulatto man with her, that passes for her husband. Her name is AMY, but very probably goes by the name of Betty Browne, having stolen an indenture of one of that name, that was bound to Thomas Jones, of Dinwiddie county, then Prince George, in the year 1744. I am informed she hath been taken up in Norfolk, and by this indenture hath gained her liberty. Any person that will apprehend the said runaway, and put her into the constable’s hands, so that I get her again, shall have TWO PISTOLES reward, besides what the law allows, paid by PARKER HARE.

By: Parker Hare

Conclusion

Running away was one form of slave resistance. Most slaves ran away relatively short distances and were not trying to permanently escape from slavery. Instead, they were temporarily withholding their labor as a form of economic bargaining and negotiation. Slavery involved a constant process of negotiation as slaves bargained over the pace of work, the amount of free time they would enjoy, monetary rewards, access to garden plots, and the freedom to practice burials, marriages, and religious ceremonies free from white oversight.

Some fugitives did try to permanently escape slavery. While the idea of escaping slavery quickly brings to mind the Underground Railroad to the free states, in fact more than half of these long-distance runaways headed southward or to cities or to natural refuges like swamps. Often, runaways were relatively privileged slaves who had served as river boatmen or coachmen and were familiar with the outside world