Evolution of Slavery

The Evolution of Slavery

At the time that Thomas Jefferson was born in 1743 most slaves were born in Africa, few were Christian, and very few slaves were engaged in raising cotton. Slavery was largely confined to eastern areas near the Atlantic Ocean and in the Carolinas and Georgia, where slaves raised rice, indigo, and tobacco. The slave population was not yet able to reproduce its numbers naturally.

By the time of Jefferson’s death in 1826, slavery had changed dramatically. A majority of slaves had been born in the New World and were capable of increasing the slave population by natural reproduction. A growing number of slaves embraced Christianity, but molded and transformed the religion to meet their own needs. Protestant Christianity held out the promise of eventual deliverance from bondage. Further, between 1790 and 1860, 835,000 slaves were moved from Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas to Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. As they were moved to the Old Southwest, hundreds of thousands of slaves were separated from their families.

The American Revolution and Slavery

The meaning and outcome of the American Revolution was intimately tied to slavery. Leaders of the Patriot cause repeatedly argued that British policies would make the colonists slaves of the British. In 1774, George Washington explained that if the colonists’ failed to aggressively assert their rights, then the British ministry “shall make us as tame and abject slaves, as the blacks we rule over with such arbitrary sway.”

Both the British and the colonists believed that slaves could serve an important role during the Revolution. In April 1775, Lord Dunmore, the Royal Governor of Virginia, threatened to free the colony’s slaves if the colonists resorted to force against his authority. In November 1775, he promised freedom to all slaves belonging to rebels who would join “His Majesty’s Troops.” Some 800 slaves joined British forces, some wearing the emblem “Liberty to the Slaves.”

Meanwhile an American diplomat, Silas Deane, hatched a secret plan to incite slave insurrections in Jamaica. Two South Carolinians, John Laurens and his father, Henry, persuaded Congress to unanimously approve a plan to recruit an army of 3,000 slave troops to stop a British invasion of South Carolina and Georgia. Under the plan, the federal government would compensate the slaves’ owners and each black would, at the war’s end, be emancipated and receive $50. The South Carolina legislature rejected the plan, scuttling the proposal.

In the end, however, and in contrast to the later Latin American wars of independence and the U.S. Civil War, neither the British nor the Americans proved willing to risk a full-scale social revolution by issuing an emancipation proclamation.

As a result of the Revolution, a surprising number of slaves were manumitted, while thousands of others freed themselves by running away. Georgia lost about a third of its slaves and South Carolina lost 25,000. Despite these losses, slavery quickly recovered in the South. By 1810, South Carolina and Georgia had three times as many slaves as in 1770.

The Revolution had contradictory consequences for slavery. In the South, slavery became more firmly entrenched. In the North, every state freed slaves as a result of court decisions or the enactment of gradual emancipation schemes.

Even in the North, there was strong resistance to emancipation. Slavery was not fully abolished in New York until 1827 and in Connecticut until 1848. Slavery did not completely end in New Jersey until the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified in 1865. Moreover, the freeing of slaves was accompanied by the emergence of a virulent form of racial prejudice in much of the North.

Antebellum Slavery

During the last years of the eighteenth century, New World slavery seemed in decline. As a result of the American and Haitian revolutions, thousands of black slaves escaped slavery through revolt or simply by running away.

Many Latin American countries and Northern colonies abolished slavery outright, while revolutionary ideals of liberty and equality encouraged many slaveowners in the South to emancipate their slaves. In the ten years after Virginia enacted a law allowing private manumissions, masters freed 10,000 slaves. A French traveler reported that people throughout the South “are constantly talking of abolishing slavery, of contriving some other means of cultivating their estates.”

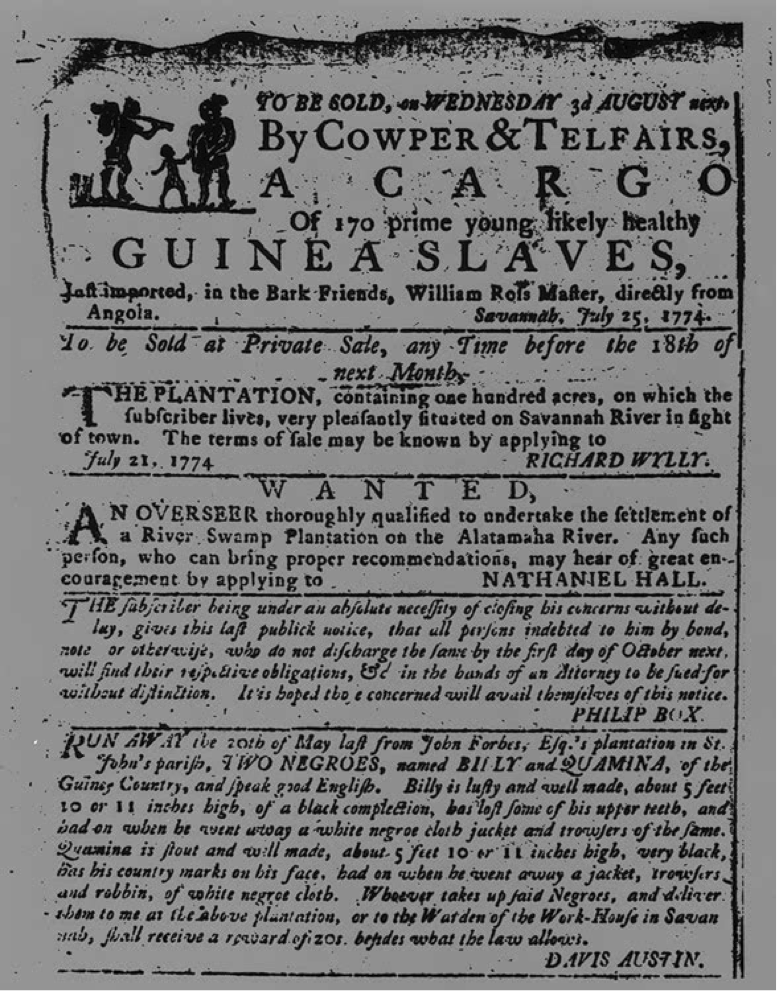

But slavery was not, in fact, on the road to extinction. Eli Whitney’s cotton gin gave slavery a new lease on life. Between 1792, when Whitney invented the cotton gin, and 1794, the price of slaves doubled. By 1825, field hands, who had brought $500 apiece in 1794, were worth $1,500. As the price of slaves grew, so, too, did their numbers.

Under Southern law, slaves were considered chattel property. Like a domestic animal, they could be bought, sold, leased, and physically punished. Slaves were prohibited from owning property, testifying against whites in court, or traveling without a pass. Their marriages lacked legal sanction. In response to abolitionist attacks on slavery, southern legislatures enacted laws setting set down minimal standards for housing, food, and clothing, but these statutes were largely unenforced.

Slave Labor

Simon Gray was a slave. He was also the captain of a Mississippi River flatboat and the builder and operator of a number of sawmills.

Emanuel Quivers, too, was a slave. He worked at the Tredegar Iron Works of Richmond, Virginia.

Andrew Dirt was also a slave. He was a black overseer.

Slaves performed all kinds of work. During the 1850s, half a million slaves lived in Southern towns and cities, where they were hired out by their owners to work in ironworks, textile mills, tobacco factories, laundries, shipyards, and mechanics’ homes. Other slaves laborered as lumberjacks, as deckhands and as fire tenders on river boats. Slaves labored in sawmills, gristmills, and quarries. Many other slaves were engaged in construction of roads and railroads.

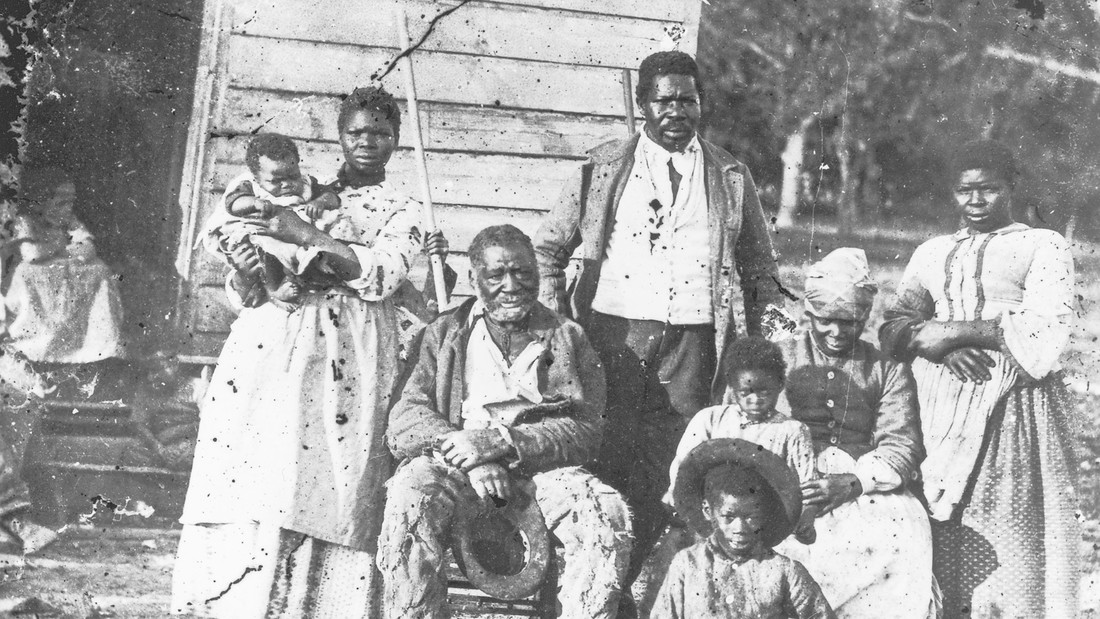

Most slaves, were fieldhands, raising cotton, hemp, rice, tobacco, and sugarcane. But some lived and worked in cities, where they were allowed to sell their labor and keep part of the proceeds.

Even on plantations not all slaves were menial laborers. Some worked as skilled artisans. such as blacksmiths, shoemakers, or carpenters. Others held domestic posts, such as coachmen or house servants. And, still others held managerial posts. At least two-thirds of the slaves worked under the supervision of black foremen of gangs, called drivers. Not infrequently they managed the whole plantation in the absence of their masters.

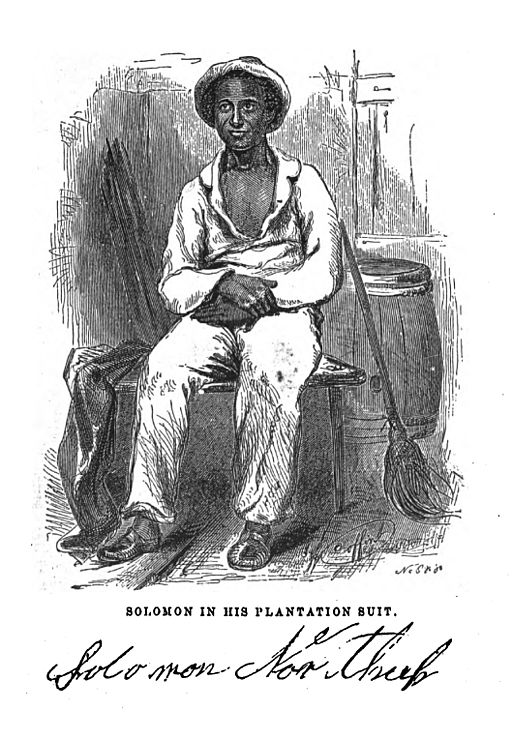

For most slaves, slavery meant backbreaking field work on small farms or larger plantations. On the typical plantation, slaves worked “from day clean to first dark.” Solomon Northrup, a free black who was kidnapped and enslaved for twelve years on a Louisiana cotton plantation, wrote a graphic description of the work regimen imposed on slaves: “The hands are required to be in the cotton field as soon as it is light in the morning, and, with the exception of ten or fifteen minutes, which is given them at noon to swallow their allowance of cold bacon, they are not permitted to be a moment idle until it is too dark to see, and when the moon is full, they often times labor till the middle of the night.”

Even after sunset, the slaves’ work was not over. It was still necessary to feed swine and mules, cut wood, and pack the cotton. At planting time or harvest time, work was even more exacting, as planters required slaves to stay in the fields fifteen or sixteen hours a day.

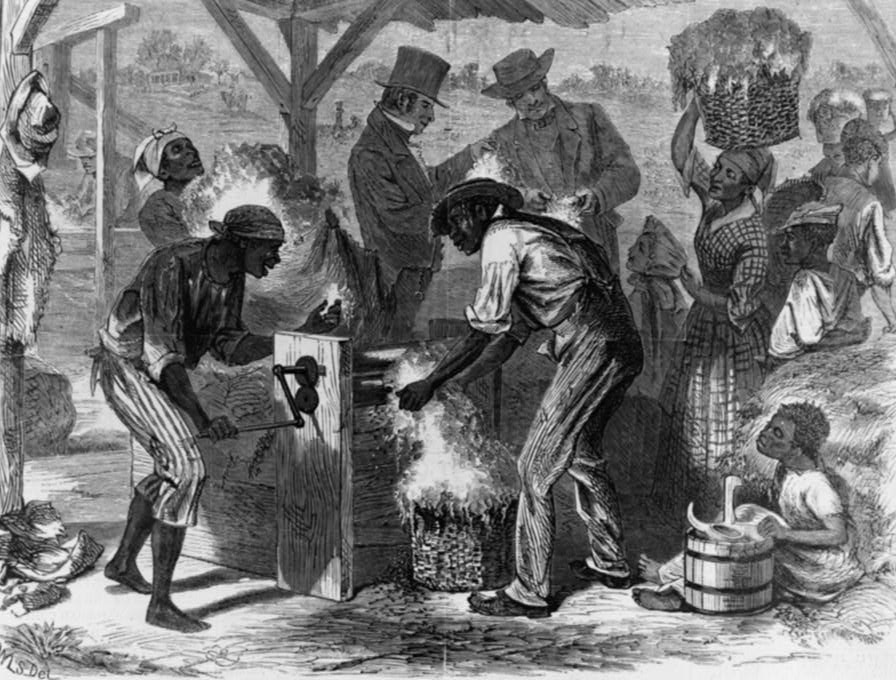

To maximize productivity, slaveowners assigned each hand a specific set of tasks throughout the year. During the winter, field slaves ginned and pressed cotton, cut wood, repaired buildings and fences, and cleared fields. In the spring and summer, field hands plowed and hoed fields, killed weeds, and planted and cultivated crops. In the fall, slaves picked, ginned, packed cotton, shucked corn, and gathered peas. Slave masters extracted labor from virtually the entire slave community–young, old, healthy, and physically impaired. Children as young as three or four were put to work, usually in special “trash gangs” weeding fields, carrying drinking water, picking up trash, and helping in the kitchen. Young children also fed chickens and livestock, gathered wood chips for fuel, and drove cows to pasture. Meanwhile, older or physically handicapped slaves were put to work in cloth houses, spinning cotton, weaving cloth, and making clothes.

Because slaves had little direct incentive to work hard, slaveowners combined a variety of harsh penalties with positive incentives. Some masters denied disobedient slaves passes or forced them to work on Sundays or holidays. Other planters confined disobedient hands to private or public jails, and one Maryland planter required a slave to eat worms he had failed to pick off tobacco plants. Chains and shackles were widely used to control runaways.

Whipping was a key part of the system of discipline and motivation. On one Louisiana plantation, at least one slave was lashed every four and a half days. In his diary, Bennet H. Barrow, a Louisiana planter, recorded flogging “every hand in the field,” breaking his sword on the head of one slave, shooting another slave in the thigh, and cutting another with a club “in 3 places very bad.” But physical pain alone was not enough to elicit hard work. To stimulate productivity, some masters gave slaves small garden plots and permitted them to sell their produce. Others distributed gifts of food or money at the end of the year. Still other planters awarded prizes, holidays, and year-end bonuses to particularly productive slaves.

History Through…

Solomon Northrup, Twelve Years a Slave: Narrative of Solomon Northrup, New York, 1853

Solomon Northrup was a free black who was kidnapped in New York and sold into slavery for twelve years. He was finally returned to freedom through the efforts of New York’s governor. In the following selection he describes how cotton was raised on his Louisiana plantation

The hands are required to be in the cotton field as soon as it is light in the morning, and, with the exception of ten or fifteen minutes, which is given them at noon to swallow their allowance of cold bacon, they are not permitted to be a moment idle until it is too dark to see, and when the moon is full, they often times labor till the middle of the night. They do not dare to stop even at dinner time, nor return to the quarters, however late it be, until the order to halt is given by the driver.

The day’s work over in the field, the baskets are “toted,” or in other words, carried to the gin‑house, where the cotton is weighed. No matter how fatigued and weary he may be—no matter how much he longs for sleep and rest—a slave never approaches the gin‑house with his basket of cotton but with fear. If it falls short in weight—if he has not performed the full task appointed him, he knows that he must suffer. And if he has exceeded it by ten or twenty pounds, in all probability his master will measure the next day’s task accordingly. So, whether he has two little or too much, his approach to the gin‑house is always with fear and trembling. Most frequently they have too little, and therefore it is they are are not anxious to leave the field. After weighing, follow the whippings; and then the baskets are carried to the cotton house, and their contents stored away like hay, all hands being sent in to tramp it down. If the cotton is not dry, instead of taking it to the gin‑house at once, it is laid upon platforms, two feet high, and some three times as wide, covered with boards or plank, with narrow walks running between them.

This done, the labor of the day is not yet ended, by any means. Each one must then attend to his respective chores. One feeds the mules, another the swine‑‑another cuts the wood, and so forth; besides, the packing is all done by candle light. Finally, at a late hour, they reach the quarters, sleepy and overcome with the long day’s toil. Then a fire must be kindled in the cabin, the corn ground in the small hand‑mill, and supper, and dinner for the next day in the field, prepared. All that is allowed them is corn and bacon, which is given out at the corncrib and smoke‑house every Sunday morning. Each one receives, as his weekly allowance, three and a half pounds of bacon, and corn enough to make a peck of meal. That is all—no tea, coffee, sugar, and with the exception of a very scanty sprinkling now and then, no salt…

An hour before day light the horn is blown. Then the slaves arouse, prepare their breakfast, fill a gourd with water, in another deposit their dinner of cold bacon and corn cake, and hurry to the field again. It is an offense invariably followed by a flogging, to be found at the quarters after daybreak. Then the fears and labors of another day begin; and until its close there is no such thing as rest…

In the month of January, generally, the fourth and last picking is completed. Then commences the harvesting of corn…Ploughing, planting, picking cotton, gathering the corn, and pulling and burning stalks, occupies the whole of the four seasons of the year. Drawing and cutting wood, pressing cotton fattening and killing hogs are but incidental labors.

Overseer Poster