Slavery in Colonial America

History as it Happened

Slavery in Colonial America

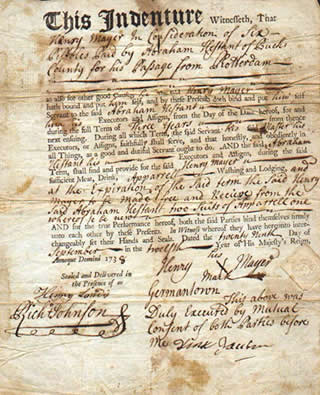

Initially, colonists in every English colony relied on indentured white servants rather than on black slaves. Thousands of England’s unemployed and underemployed farmers, urban labors, debtors, and criminals were sent as indentured servants to the New World, where they might contribute to England’s wealth by raising tobacco or producing other goods. More than half of all white immigrants to the English colonies during the seventeenth century consisted of convicts or indentured servants.

Indentured servants agreed to work for a four or five-year term of service in return for their transportation to the New World as well as food, clothing, and shelter. Like slaves, servants could be bought, sold, or leased, and be punished by whipping. But unlike slaves, servants were freed at the end of their term of service.

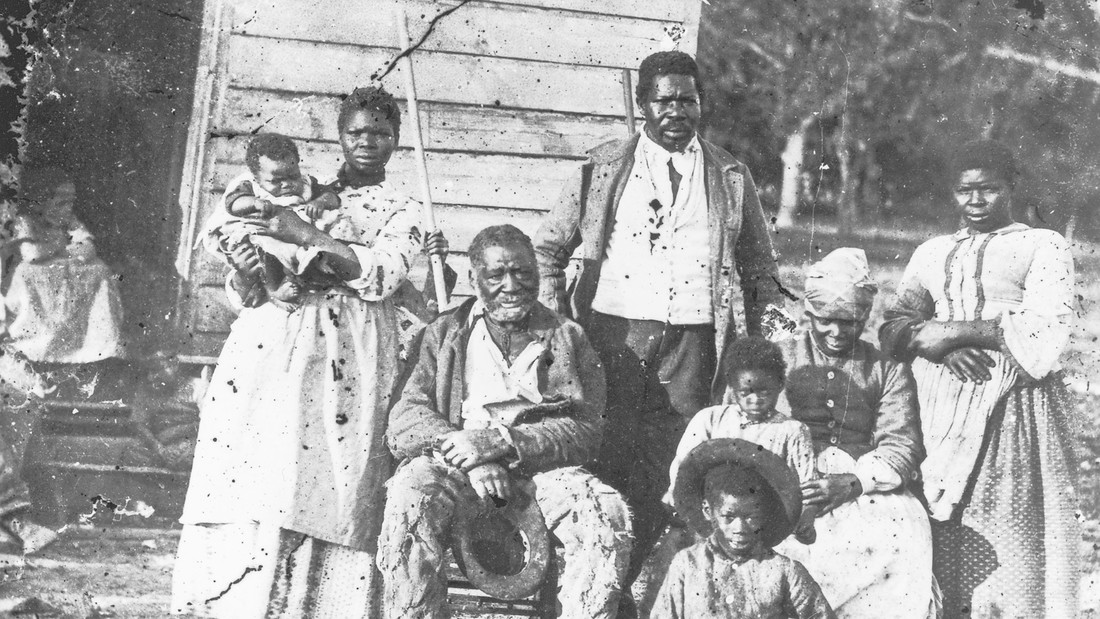

Slavery took root in the American colonies slowly. As early as 1619, a Dutch ship carried what were probably the first Africans to Virginia, but it would not be until the 1680s that black slavery became the dominant labor system on plantations. As late as 1640, there were probably only 150 blacks in Virginia (the colony with the highest black population), and in 1650, 300. But by 1680, the number had risen to 3,000 and by 1704, to 10,000. Faced by a shortage of white indentured servants and fearful of servant revolt, English settlers increasingly resorted to enslaved Africans.

Between 1700 and 1775, more than 350,000 Africans slaves entered the American colonies. By the mid-eighteenth century, blacks made up almost seventy percent of the population of South Carolina, forty percent in Virginia, eight percent in Pennsylvania, and four percent in New England. Slavery was a legal institution in all of the thirteen American colonies. But slavery during the colonial era was not a static, unchanging institution. It underwent profound changes during the first two centuries of English settlement.

During the early-seventeenth century, some blacks were permanently unfree while others were treated like white indentured servants. They were allowed to own property and to marry and were freed after a term of service. In several cases, black slaves who could prove that they had been baptized successfully sued for their freedom.

As early as the late 1630s, English colonists began to make a sharper distinction between the status of white servants and black slaves. In 1639, Maryland became the first colony to state that baptism as a Christian did not make a slave a free person. In 1669, Virginia became the first colony to declare that it was not a crime to kill an unruly slave in the ordinary course of punishment. By the end of the seventeenth century, Virginia and Maryland had forbidden interracial marriages and sexual relations.

Laws adopted in several colonies in the early-eighteenth century confiscated slaves’ property, forbid masters from freeing their slaves, permitted masters to mutilate and dismember disobedient slaves, and declared that slave status was inherited through the mother.

During the late-seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, three distinctive systems of slavery emerged in the American colonies. In the Chesapeake colonies of Maryland and Virginia, slaves were worked in gangs to raise tobacco, corn, and other grains. Eager to encourage a rapid population increase, slave owners in the Chesapeake consciously imported many female slaves. Beginning in the 1720s, slaves in the Chesapeake region became the first slave population in the New World able to naturally reproduce their numbers.

In the South Carolina and Georgia Low Country, slaves that raised rice and indigo were able to reconstitute African social patterns and to develop a distinctive dialect known as, Gullah. In this region, the “task system,” rather than gang labor, became the norm. Each day, slaves were required to achieve a precise work objective. This allowed enslaved Africans to leave the fields early in the afternoon to tend their own gardens and raise their own livestock.

In the North, slavery was concentrated on Long Island and in southern Rhode Island and New Jersey, where slaves were engaged in farming and stock raising for the West Indies. But many slaves served as household servants for the urban elite or as unpaid laborers for master craftsmen. In 1690, one out of every nine families in Boston owned a slave. In New York City in 1703, two out of every five families owned a slave. Northern slave owners included John Jay, the first Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court and Aaron Burr, Vice President under Thomas Jefferson. President Martin Van Buren of New York was a descendant of a Dutch slave-holding family. Benjamin Franklin owned slaves for a short time.