The Middle Passage

The Visual History of Slavery

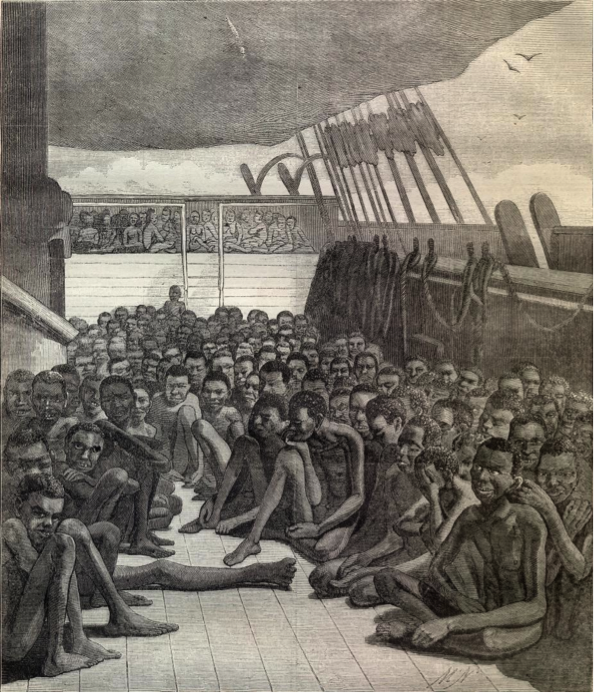

In the following sections, the visual history of slavery will also be explored. Histories of slavery generally draw upon written evidence: letters, diaries, account books, plantation records, and published slave narratives. Other forms of evidence, especially visual evidence, have not received the attention they deserve.

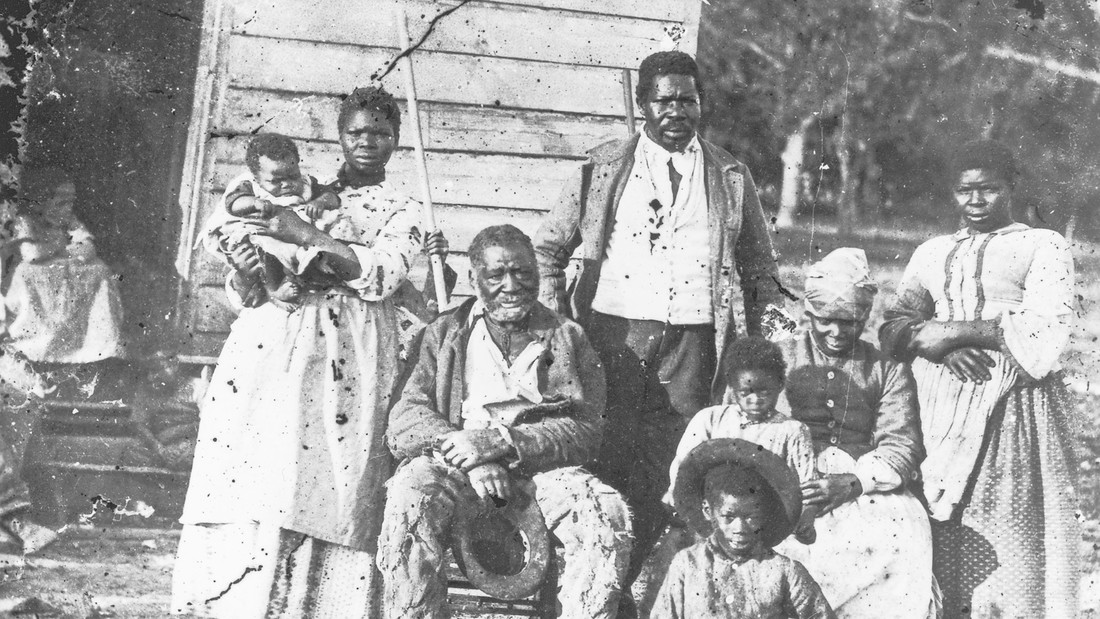

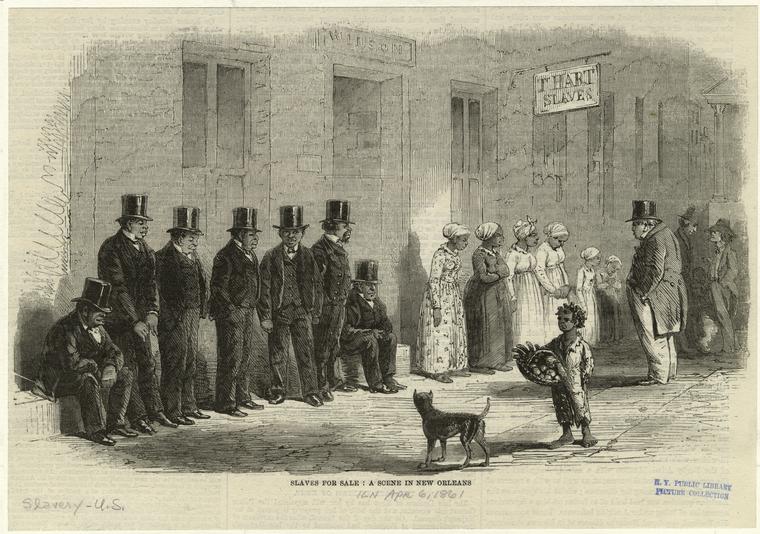

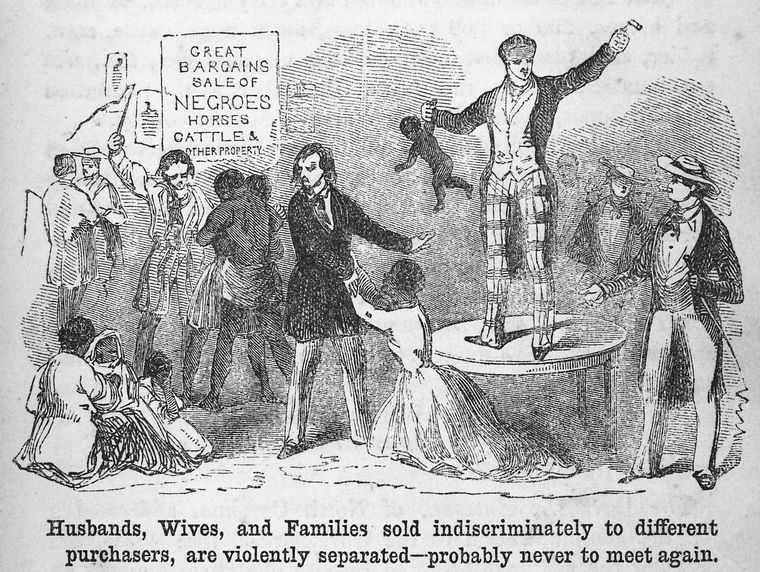

During the nineteenth century, visual representations of slavery—paintings, engravings, daguerreotypes, and photographs—proliferated. These images help us visualize slavery’s oppressive realities in ways that written documents cannot. We can actually see a slave coffle, a slave ship, an auction, a whipping, a funeral, or a religious service. We can envision slave’s dress and demeanor.

But, interpreting visual evidence is no easy task. Only rarely does the visual evidence offer an objective depiction of life in bondage as it actually was. Rather, the visual representations are colored by cultural stereotypes, artistic conventions, and ideological presuppositions. Visual images are not simply objective representations of reality. These images are rich cultural texts, and we need to explore their cultural and ideological meaning.

During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, visual images of slavery were frequently used as propaganda in the battle between pro- and anti-slavery forces. Apologists for slavery created a host of images that implied that slaves were contented within slavery, loyal to their masters, and incapable of adapting to freedom or to an urban environment. Many of these deeply derogatory images depicted slaves in ways that we quite rightly find profoundly offensive. Slaves are portrayed as animalistic, primitive, uncivilized, or ludicrously dressed.

Artists with anti-slavery leanings, in contrast, sometimes created works that were highly individualized and realistic. Some artists who opposed slavery created works that were decidedly sentimental while others depicted slaves as passive and submissive.

To interpret a visual representation of slavery, we must assess their creator’s intentions and ask how these images were understood by those who viewed them.

Among the questions we might ask are these:

- What was the function of a particular image? Was it intended to document the realities of slavery or was it intended to persuade?

- What emotions does the image evoke and what issues, ideas, or conflicts does the image reveal?

- Does the image provide an accurate representation of slavery or is the picture it presents sentimentalized, sanitized, or distorted?

- Do the images portray slaves as realistic individuals or as caricatures?

- Are enslaved African Americans depicted as powerless and passive victims or as assertive individuals who were able to create a culture supportive of human dignity within the confines of slavery?

The Middle Passage

The trans-Atlantic slave trade was the largest movement of people in history. Between ten and fifteen million Africans were forcibly transported across the Atlantic between 1500 and 1900. Indeed, at least four times more Africans arrived in the New World compared to Europeans.

The trans-Atlantic slave trade was deadly. At least two million Africans—ten to fifteen percent—died during the infamous “Middle Passage” across the Atlantic.

The level of slave exports to the New World grew from about 36,000 per year in the early eighteenth century to almost 80,000 per year during the 1780s. By 1750, slavers usually contained at least four hundred slaves, with some carrying more than seven hundred.

Once on shipboard, slaves were chained together and crammed into spaces sometimes less than five feet high. Inside the hold, slaves had only half the space provided for indentured servants or convicts. Urine, vomit, mucous, and horrific odors filled the hold.

The Middle Passage usually took more than seven weeks. Men and women were separated, with men usually placed toward the vessel’s bow and women toward the stern. The men were chained together and forced to lie shoulder to shoulder, while women were usually left unchained. During the voyage, the enslaved Africans were typically fed only once or twice a day and brought on deck for limited times. Many Africans resisted enslavement. Many captives mutinied, attempted suicide, jumped overboard, or refused to eat. The most recent estimate suggests that there was a revolt on one in every ten voyages across the Atlantic.

Upon arrival in the New World, enslaved Africans underwent the final stage in the process of enslavement, known as “seasoning.” Many slaves died of disease or suicide, but many other African captives conspired to escape slavery by running away and forming “maroon” colonies in remote parts of South Carolina, Florida, Brazil, Guiana, and Jamaica, and Surinam.

Sight and Sound

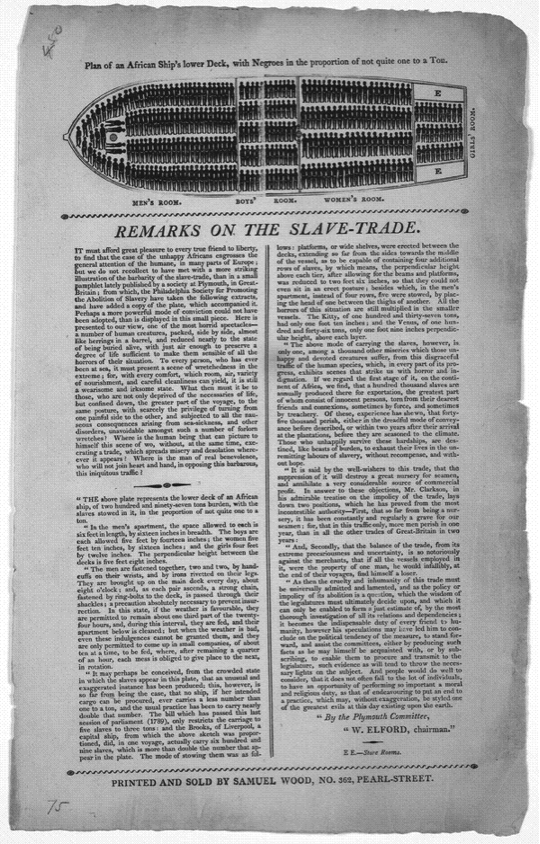

Lower Deck

On this ship, adult men were allotted space six feet in length and sixteen inches in breadth. Boys were allowed five feet in length and fourteen inches in breadth, adult women five feet, ten inches by sixteen inches; and girls, four feet by twelve inches.

The height between the ship’s decks was just five feet, eight inches. On some ships, shelves were erected between decks, reducing the head room to just two feet, six inches.

The men were fastened together with handcuffs and leg irons. When weather was favorable, they were allowed about eight hours on deck, but when the weather was foul, the were only allowed about fifteen minutes on the main deck.

Sight and Sound

On the Deck of a Slave Ship

The transatlantic voyage lasted at least five weeks and sometimes as long as three months. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, shipboard death rates ran as high as fifteen percent or more.

By the late eighteenth century, rates had fallen to about five percent, remaining twice the rate for white immigrants. Insurrections occurred on about one voyage in ten.

This illustration depicts the treatment of 510 Africans on board the bark, Wildfire, which was apprehended while trying to smuggle slaves into the United States in 1860. The freed captives were then transported to Liberia.