Historical Perspective

Thinking Comparatively

Slavery in a Historical Perspective

During the decades before the Civil War, slavery was often called “the peculiar institution.” But throughout much of human history, free wage labor, not forced labor, was the truly peculiar institution. Most people worked not out of a desire to better their condition in life, but because they were forced to do so.

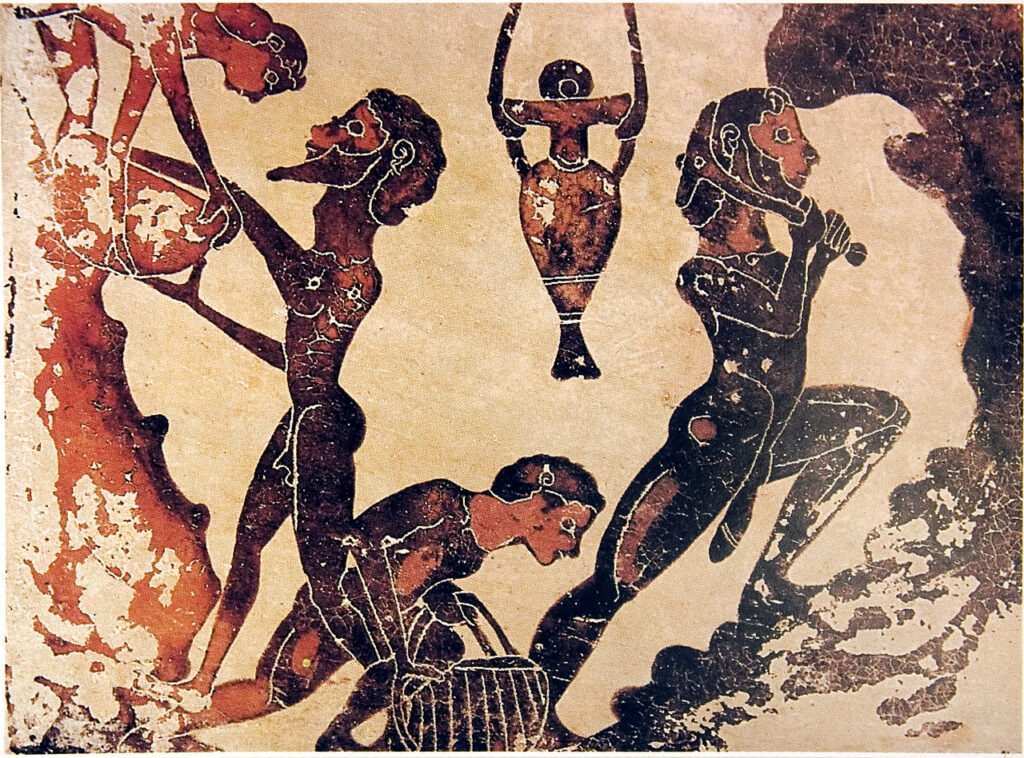

Slavery dates to prehistoric times and the institution could be found in the world’s earliest civilizations along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in Mesopotamia, the Nile in Egypt, the Indus Valley of India, and China’s Yangtze River Valley. At the time of Christ, there were probably between two and three million slaves in Italy, making up thirty-five to forty percent of the population. England’s Domesday Book of 1086 indicated that ten percent of the English population was enslaved. Among some Indian tribes of the Pacific Northwest, nearly a quarter of the population consisted of slaves.

Although slavery gradually disappeared in northwestern Europe, where it was replaced by serfdom, it persisted in Sicily, southern Italy, Russia, southern France, Spain, and North Africa. It is notable that the modern word for slaves came from “Slav.” During the Middle Ages, most slaves in Europe and the Islamic world were people from Slavic Eastern Europe. It was only in the fifteenth century that slavery became linked with people from sub-Saharan Africa.

When Western Europeans began to colonize the New World at the end of the fifteenth century, they were well aware of the institution of slavery. As early as 1300, Europeans were using black and Russian slaves to raise sugar on Italian plantations. During the 1400s, decades before Columbus’s “discovery” of the New World, Europeans exploited African labor on slave plantations on sugar producing islands off the coast of West Africa.

During the sixteenth century, Portugal and Spain extended racial slavery into the New World, opening sugar, coffee, and cotton plantations in Brazil and the West Indies and forcing black slaves in Mexico to work in mines. During the seventeenth century, England, France, Denmark, and Holland established slavery in their New World colonies.

The slavery that developed in the New World was different from that found in classical antiquity and in Africa and Asia. For one thing, slavery in the classical and the early medieval worlds was not based on racial distinctions. In ancient Rome, for example, the slave population included Ethiopians, Gauls, Jews, Persians, and Scandinavians.

Another distinction between modern and ancient slavery was that the ancient world did not necessarily regard slavery as a permanent condition. In many societies, slaves were allowed to marry free spouses and become members of their owners’ families.

A third key difference between ancient and modern slavery was that slaves did not necessarily hold the lowest status in pre-modern societies. The Bible tells the story of Joseph, who was sold into slavery by his brothers and who became a trusted governor, counselor, and administrator in Egypt. In classical Greece, many educators, scholars, poets, and physicians were in fact slaves. And in ancient Rome, slaves ranged from those who labored in mines to many merchants and urban craftsmen. In the ancient Near East, slaves could conduct trade and business on their own. In certain Muslim societies, rulers were customarily recruited among the sons of female slaves.

Finally, it was only in the New World that slavery provided the labor force for a high pressure, profit-making capitalist system of plantation agriculture producing cotton, sugar, coffee, and cocoa for distant markets.

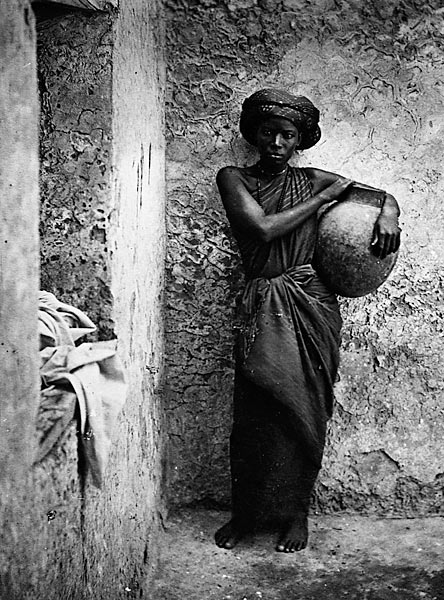

While many slaves in the ancient and non-western world toiled in mines and agricultural fields, or on construction and irrigation projects, and suffered extremely high death rates, most slaves were household servants or concubines or eunuchs. In general, these peoples did not subject slaves to the kind of regimented efficiency found on slave plantations in the West Indies or the American South. They were symbols of prestige, luxury, and power rather than a source of labor.

Justifications of Slavery

Over time, justifications for slavery changed profoundly. Many ancient societies considered slavery a matter of bad luck or accident. Slaves in these societies were often war captives or victims of piracy or children who had been abandoned by their parents. Greek philosopher, Aristotle, developed the notion that some people were “natural slaves” who lacked the higher qualities of the soul necessary for freedom.

In the Christian world, the most important rationalization for slavery was the so-called “Curse of Ham.” According to this doctrine, the Biblical figure, Noah, had cursed his son, Ham, with blackness and the condition of perpetual slavery. In fact, this story rested on a misunderstanding of the Biblical text. In the Bible, Noah curses Canaan, the ancestor of the Canaanites, not Ham. But the “Curse of Ham” remains important in that it was the first justification of slavery based on ethnicity.

It was not until the late-eighteenth century that pseudo-scientific racism provided the basic rationale for slavery.

Slavery in Africa

Slavery existed in Africa before the arrival of Europeans—as did a slave trade that exported a small number of sub-Saharan Africans to North Africa, the Middle East, and the Persian Gulf. However, the kinds of slavery found in Africa differed profoundly from the system of plantation slavery that developed in the New World.

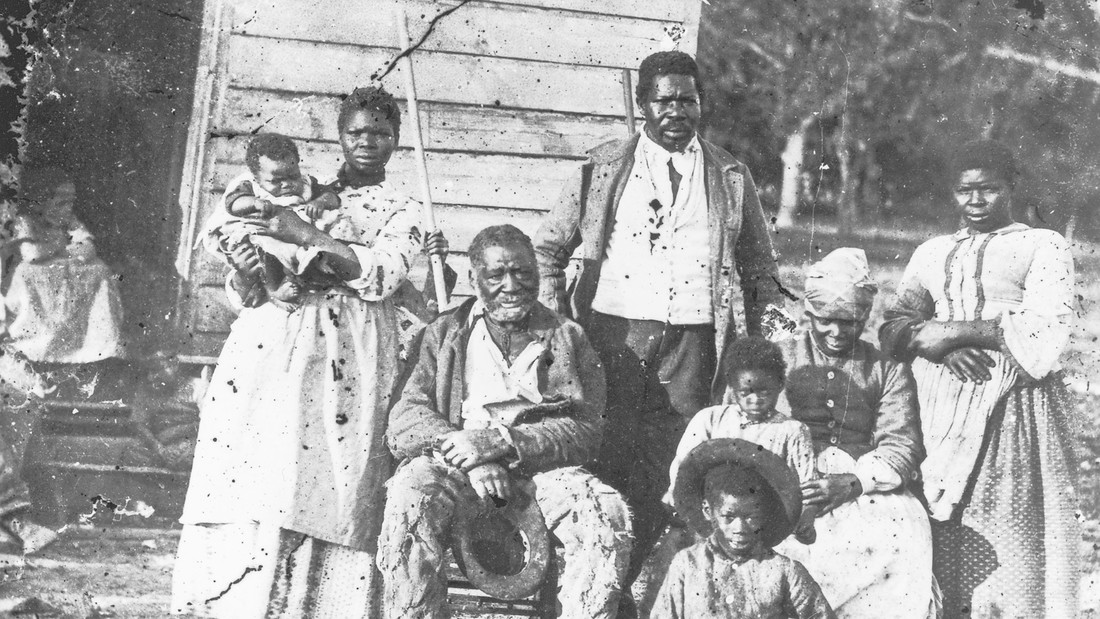

For one thing, hereditary slavery, extending over several generations, was rare. Many African slaves were eventually freed and absorbed into their owner’s kin group. Another difference was that in African societies most slaves were female. Women were preferred because they bore children and performed most field labor. While most slaves were field workers, some served in royal courts, where they served as officials, soldiers, servants, and artisans.

The trans-Atlantic trade profoundly changed the nature and scale of slavery in Africa itself and imposed a heavy economic, political, and psychological cost on the continent. The development of the Atlantic slave trade led to the enslavement of far greater numbers of Africans and to more intense exploitation of slave labor within Africa.

The slave trade had an enormous impact on African society. One of its most profound consequences was demographic. While the trade probably did not reduce the overall population, it did produce a radically skewed sex ratio. During the slave trade era, in most parts of West and Central Africa there were only 80 men in the age bracket 15-60 for every 100 women. In Angola, there were just 40 to 50 men per 100 women. As a result of the slave trade, there were fewer adult men to hunt, fish, rear livestock, and clear fields.

The slave trade also generated violence, spread disease, and resulted in massive imports of European goods, undermining local industries. It also slowed population growth. According to one estimate, in the absence of the slave trade, there would have been 100 million Africans in 1850 instead of 50 million.

Why was Africa so vulnerable to the slave trade?

The answer lies in West and Central Africa’s political fragmentation. By the era of the slave trade, many of the region’s larger political units—such as the empires of Ghana and Mali—had declined. The absence of strong, stable political units made it more difficult for smaller states to resist the slave trade.

In retrospect, it seems clear that the Atlantic slave trade depended upon a highly complex set of variables. Trade winds and ocean currents made it easy to sail from the western African coast to Brazil and the Caribbean. The importation of new food crops from the Americas—such as cassava, squash, and peanuts—stimulated population growth in Africa. Rapid population growth, in turn, made the slave trade possible.

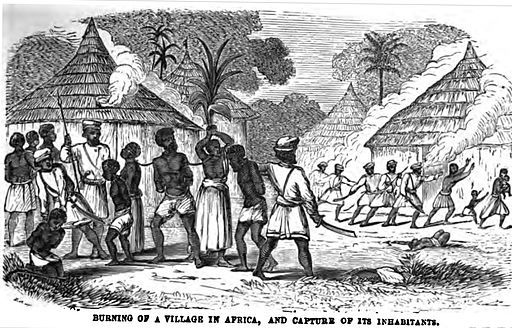

How were people enslaved? Most slaves in Africa were captured in wars or in surprise raids on villages. Adults were bound and gagged and infants were sometimes thrown into sacks. Others were enslaved as punishment for crime or to repay a debt.

After enslavement, the captives were bound together at the neck and marched barefoot hundreds of miles to the Atlantic coast. Observers reported seeing hundreds of skeletons along the slave caravan routes. At the coast, the captives were held in pens (known as barracoons) guarded by dogs. Our best guess is that 15 to 30 percent of Africans died during capture, the march from the interior, or the wait for slave ships along the coast.

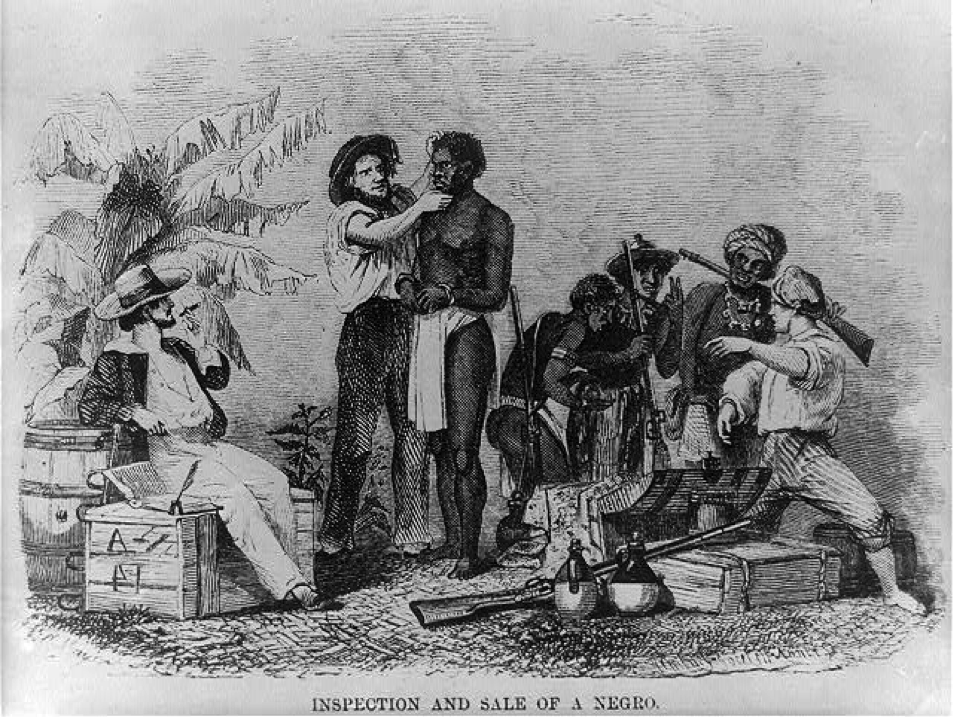

Slave Inspections