New World Colonization

English Colonization Begins

During the early and mid-sixteenth century, the English tended to conceive of North America as a base for piracy and harassment of the Spanish. But by the end of the century, the English began to think more seriously about North America as a place to colonize: as a market for English goods and a source of raw materials and commodities, such as furs. English promoters claimed that New World colonization offered England many advantages. Not only would it serve as a bulwark against Catholic Spain, it would supply England with raw materials and provide a market for finished products. America would also provide a place to send the English poor and ensure that they would contribute to the nation’s wealth.

During the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, the English poor population increased rapidly. As a result of the enclosure of traditional common lands (which were increasingly used to raise sheep), many common people were forced to become wage laborers or else to support themselves hand-to-mouth or simply as beggars.

After unsuccessful attempts to establish settlements in Newfoundland and at Roanoke, the famous “Lost Colony,” off the coast of present-day North Carolina, England established its first permanent North American settlement, Jamestown, in 1607. Located in swampy marshlands along Virginia’s James River, Jamestown’s residents suffered horrendous mortality rates during its first years. Immigrants had just a fifty-fifty chance of surviving five years.

The Jamestown expedition was financed by the Virginia Company of London, which believed that precious metals were to be found in the area. From the outset, however, Jamestown suffered from disease and conflict with Indians. Approximately 30,000 Algonquian Indians lived in the region, divided into about forty tribes. About thirty tribes belonged to a confederacy led by Powhatan.

Food was an initial source of conflict. More interested in finding gold and silver than in farming, Jamestown’s residents (many of whom were either aristocrats or their servants) were unable or unwilling to work. When the English began to seize Indian food stocks, Powhatan cut off supplies, forcing the colonists to subsist on frogs, snakes, and even decaying corpses.

Captain John Smith (1580?-1631) was twenty-six years old when the first expedition landed. A farmer’s son, Smith had already led an adventurous life before arriving in Virginia. He had fought with the Dutch army against the Spanish and in Eastern Europe against the Ottoman Turks, when he was taken captive and enslaved. He later escaped to Russia before returning to England.

Smith, serving as president of the Jamestown colony from 1608 to 1609, required the colonists to work and traded with the Indians for food. In 1609, after being wounded in a gunpowder accident, Smith returned to England. After his departure, conflict between the English and the Powhatan confederacy intensified, especially after the colonists began to clear land in order to plant tobacco.

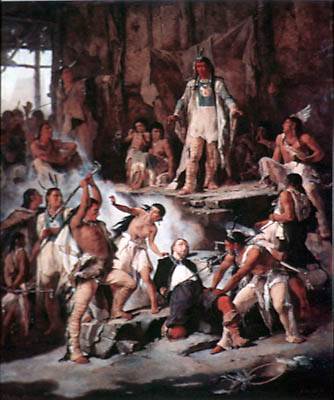

In a volume recounting the history of the English colony in Virginia, Smith describes a famous incident in which Powhatan’s 12-year-old daughter, Pocahontas (1595?-1617), saved him from execution. Although some have questioned whether this incident took place (since Smith failed to mention it in his Historie‘s first edition), it may well have been a “staged event,” an elaborate adoption ceremony by which Powhatan symbolically made Smith his vassal or servant. Through similar ceremonies, the Powhatan people incorporated outsiders into their society.

Pocahontas reappears in the colonial records in 1613, when she was lured aboard an English ship and held captive. Negotiations for her release failed, and in 1614, she married John Rolfe, the colonist who introduced tobacco to Virginia. Whether this marriage represented an attempt to forge an alliance between the English and the Powhatan remains uncertain.

Life in Early Virginia

The story of early Virginia is a story of starvation and cannibalism in the midst of plenty, idleness in a fertile, game-rich land, and brutal warfare with the Indians on whom the Virginians depended for food.

Early Virginia was a frightful, brutal, mismanaged place. Punishments for those who violated rules were unspeakably awful. Transgressors were hanged, burned, broken on the wheel, staked to the ground, or shot.

Early Virginia was a death trap. Of the first 3,000 immigrants, all but 600 were dead within a few years of arrival. Virginia was a society in which life was short, diseases ran rampant, and parentless children and multiple marriages were the norm.

In sharp contrast to New England, which was settled mainly by families, most of the settlers of Virginia and neighboring Maryland were single men bound in servitude. Before the colonies turned decisively to slavery in the late seventeenth century, planters relied on white indentured servants from England, Ireland, and Scotland. They wanted men, not women. During the early and mid-seventeenth century, as many as four men arrived for every woman.

Why did large numbers of people come to such an unhealthful region? To raise tobacco, which had been introduced into England in the late sixteenth century. Like a number of other consumer products introduced during the early modern era–like tea, coffee, and chocolate—tobacco was related to the development of new work patterns and new forms of sociability. Tobacco appeared to relieve boredom and stress and to enhance peoples’ ability to concentrate over prolonged periods of time. Tobacco production required a large labor force, which initially consisted primarily of white indentured servants, who received transportation to Virginia in exchange for a four to seven-year term of service.

Lacking valuable minerals or other products in high demand, it appeared initially that Jamestown was an economic failure. After ten years, however, the colonists discovered that Virginia was an ideal place to cultivate tobacco, which had been recently introduced into Europe. Since tobacco production rapidly exhausted the soil of nutrients, the English began to acquire new lands along the James River, encroaching on Indian hunting grounds.

In 1622, Powhatan’s successor, Opechcanough, tried to wipe out the English in a surprise attack. Two Indian converts to Christianity warned the English; still, 347 settlers, or about a third of the English colonists, died in the attack. Warfare persisted for ten years, followed by an uneasy peace. In 1644, Opechcanough launched a last, desperate attack. After about two years of warfare, in which some 500 colonists were killed, Opechcanough was captured and shot and the survivors of Powhatan’s confederacy, now reduced to just 2,000, agreed to submit to English rule.

Raising tobacco required a large labor force. At first, it was not clear that this labor force would consist of enslaved Africans. Virginians experimented with a variety of labor sources, including Indian slaves, penal slaves, and white indentured servants. Convinced that England was overpopulated with vagabonds and paupers, the colonists imported surplus Englishmen to raise tobacco and to produce dyestuffs, potash, furs, and other goods that England had imported from other countries. Typically, young men or women in their late teens or twenties would sign a contract of indenture. In exchange for transportation to the New World, a servant would work for several years (usually four to seven) without wages.

The status of indentured servants in early Virginia and Maryland was not wholly dissimilar from slavery. Servants could be bought, sold, or leased. They could also be physically beaten for disobedience or running away. Unlike slaves, however, they were freed after their term of service expired, their children did not inherit their status, and they received a small cash payment of “freedom dues.”

The English writer, Daniel Defoe (1661?-1731), set part of his novel Moll Flanders (1683) in early Virginia. Defoe described the people who settled in Virginia in distinctly unflattering terms: There were convicts, who had been found guilty of felonies punishable by death, and there were those “brought over by masters of ships to be sold as servants. Such as we call them, my dear, but they are more properly called slaves.”

George Alsop, an indentured servant in Maryland, echoed these sentiments in 1666. Servants “by hundreds of thousands” spent their lives “here and in Virginia, and elsewhere in planting that vile tobacco, which all vanishes into smoke, and is for the most part miserably abused.” And, he went on, this “insatiable avarice must be fed and sustained by the bloody sweat of these poor slaves.”

Hollywood Versus History

The Disneyfication of America’s Colonial Past

More than any other company, Walt Disney has demonstrated an ongoing interest in American history. From the adventures of Davy Crockett, to the animatronic Abraham Lincoln robot at Disneyland, and the attempt to build an American history theme park near the Bull Run battlefield, Disney has long looked to American history as a source of entertainment, edification, and profit. Yet despite its fascination with history, Walt Disney has been a corporation historians love to hate.

Why don’t historians like Disney? Is it because historians fear competition and are eager to monopolize control over the past? Perhaps. But it is also because Disney epitomizes the way that popular culture sentimentalizes and caricatures American history, stripping it of its complexity, conflict, drama, and meaning.

To understand the ways that a particular Disney film, Pocahontas, distorts and sanitizes the past, it is helpful to understand the various forms historical films have taken and the changing way they have been perceived. It is at the movies that many viewers obtain their most vivid images of the past. From the beginnings of motion pictures, movie-makers have turned to history for many of its most compelling stories.

No one expects a film to be a schoolbook, held to the same standards of accuracy and rigor as a scholarly article. Even the most impressive historical movies, like the films Glory or Schindler’s List, engage in dramatic license, inventing dialogue, manipulating or embellishing facts, combining or concocting characters, condensing events, collapsing time, or injecting romance. Nitpicking, however, does little to help us understand why a historical film might resonate with the audience at a particular time. Nor does an obsession with accuracy help us understand how a film might cause us to critically reflect on the past.

Yet despite their factual inaccuracies, we must recognize that there are some things that movies can do better than a historical text. Movies are often better than history books at capturing the atmosphere and look of a particular time. They can help us visualize the past in a way that few scholars can. But great historical movies can do something more: they can illuminate a historical figure’s character, clarify moral, or political issues, and expose a mass audience to an important but forgotten incident from the past.

The 1995 animated musical, Pocahontas, offers Walt Disney’s take on the early seventeenth-century encounter between the English and Powhatan Indians near Jamestown in Virginia. Featuring romance, anthropomorphized animals, and a talking tree, the film has little problems and big ones too. We might begin with a small example. The Disney film shows a youthful, clean shaven, blond John Smith with the voice of Mel Gibson. The real John Smith was a bearded Renaissance soldier who had been a pirate, a beggar in Ireland, and a mercenary for the kingdom of Hungary. Pocahontas herself was just twelve to fourteen at the time she first encountered John Smith, not the older teenager depicted in the film.

Then there are larger problems. Pocahontas illustrates five psychological mechanisms that Americans have used to evade the true meaning of our collective past. One such mechanism is a screen memory. An important concept in Sigmund Freud’s system of psychoanalysis, a screen memory, is a recollection of early childhood that is falsely recalled or magnified in importance, masking other memories of deeper significance.

Nations, like individuals, can have screen memories. As schoolchildren, we all learned a series of legends that suggest that relations between the English and the indigenous people were more cooperative and less acrimonious than they actually were. Each Thanksgiving, schoolchildren recite the story of Squanto, the Patuxet Indian, who taught the Pilgrims how to plant corn. Schoolchildren are also familiar with William Penn, the founder of Pennsylvania, who promised fair dealings with his region’s native people. But the most famous legend of all involves Pocahontas’s rescue of Captain John Smith.

The Pocahontas legend, like the story of Squanto and of William Penn, allows present-day Americans to evade the ugly realities of relations between English colonizers and the indigenous people.

The true story of English settlement in Virginia was a nauseating story of conflict, failed negotiations, and cultural and racial warfare. Pocahontas’s brief life illustrates the stomach-churning collision of cultures that occurred when English colonists arrived in colonial America.

Born about 1595, Pocahontas was a daughter of Powhatan, the leader of a powerful Indian confederacy. Comprised of some 30 tribes totaling about 20,000 people, the confederacy occupied much of what is now known as Virginia. She was about twelve years old when the English established their first permanent America settlement at Jamestown and when she purportedly rescued John Smith.

When she was about fourteen, she reportedly married a chief in her tribe. Temporarily, she disappears from the colonial records only to reappear in 1613, when she was lured aboard an English ship and held captive. Her marriage in 1614 to John Rolfe, the Virginia settler who learned how to cure tobacco, helped bring a temporary peace between the English and the Powhatan confederacy. After her marriage, Pocahontas converted to Christianity and adopted an English name, Rebecca.

Her story ended tragically. In 1616, she went with her husband to London to help raise funds for the struggling colonists in Virginia. The English celebrated her as an Indian “princess,” but while she was waiting to return to America, she contracted smallpox and died in 1617—one of countless Indians to die from European diseases.

According to a story told by Captain John Smith in an account published years after the purported event, he was captured while exploring the Virginia countryside. Powhatan was about to have him executed when Pocahontas intervened. We do not know if the episode took place. If it did, it is unlikely that it occurred as described by John Smith. Its meaning and significance were almost certainly far different than the film portrays. Pocahontas’s rescue of John Smith from beheading was most likely a staged event. It was a ritual of adoption—not an actual execution. The Powhatans used mock executions as a symbolic way to incorporate vassals or subordinates into their society.

A second basic defense mechanism is known as splitting. It involves dividing a complex reality into dualities or polar opposites. Splitting has played a critical role in European perceptions of Indians. In early accounts, Indians were depicted either noble children of nature or as bloodthirsty savages. Such stereotypes have been updated, with native peoples depicted either proto-ecologists or as a primitive people. The realities, of course, are far more complex, and do not conform to such simplistic categories.

A third basic defense mechanism is projection or displacement. This involves attributing one’s own feelings, ideas, or attitudes onto some other people or objects. Today, Americans feel very uneasy about race relations, our treatment of the environment, and the materialism of our society.

One way to deal with these anxieties is to displace them into the distant past. The film, Pocahontas, projects present-day concerns about ethnic relations, tolerance, and environmentalism into the distant past, obscuring the difference between the past and the present.

A fourth psychological mechanism involves transference—a process in which certain emotions and desires are inappropriately shifted elsewhere. The story of a European colonizer, depicted as strong, white, and intensely masculine, who is rescued from savages by the love of a dark, sensual, deeply feminine princess, is a repeated theme in the literature of colonization. This is a common fantasy about colonialism—that the people whose land is being colonized eagerly embrace their conquerors.

A final psychological defense that Americans frequently resort to might be termed “depersonalization.” It treats events as inevitable, as the product of impersonal forces rather than of human agency. It involves the externalization of blame, guilt, or responsibility.

This view is a gross distortion of history. Far from being passive victims, Native Americans were active agents who responded to threats to their cultures through negotiation, physical resistance, and cultural adaptation. Pocahontas herself was no mere passive figure. In real life, she played a critical mediating role between two cultures. She was what anthropologists and ethnohistorians call a cultural intermediary and interpreter. In colonial encounters, some women have often played a critical mediary role: to forge alliances, to facilitate communication and to instruct both sides in diplomacy.

Pocahontas is a well-intentioned movie. It is a plea for tolerance and ecological awareness in a world torn by ethnic strife and environmental degradation. It transforms the Pocahontas legend into cultural critique—a critique of ethnocentrism, materialism, possessiveness, and greed. Who could possibly be opposed to this?

Yet, the film is historically misleading. It omits the larger context of colonial expansion and violent resistance. It does not suggest that Pocahontas’ future husband, John Rolfe, was apparently the first Englishman to grow tobacco in Virginia—which stimulated a rush for Indian land. Nor does the film mention that in 1622, Pocahontas’ brother led an assault that killed a third of the English settlers, including Pocahontas’ English husband.

It would be almost impossible to imagine Hollywood making a lighthearted musical about Ann Frank and the Holocaust, the destruction of European Jewry. But the cinematic Pocahontas is, in certain respects, something like that.