New England in Comparative Perspective

Thinking Comparatively

New England in Comparative Perspective

There were significant demographic and economic contrasts between the Chesapeake region and New England. Because of its cold winters and low population density, seventeenth-century New England was perhaps the most healthful region in the world. After an initial period of high mortality, life expectancy quickly rose to levels comparable to our own. Men and women, on average, lived about sixty-five to seventy years, fifteen to twenty years longer than in England. One result was that seventeenth-century New England was the first society in history in which grandparents were common.

Descended largely from families that arrived during the 1630s, New England was a relatively stable society settled in compact towns and villages. It never developed any staple crop for export of any consequence, and about ninety to ninety-five percent of the population was engaged in subsistence farming.

The further south one looks, however, the higher the death rate and the more unbalanced the sex ratio. In New England, men outnumbered women about three to two in the first generation. But in New Netherlands there were two men for every woman and the ratio was six to one in the Chesapeake region. Where New England’s population became self-sustaining as early as the 1630s, New Jersey and Pennsylvania did not achieve this until the 1660s to the 1680s, and Virginia not until after 1700. Compared to New England, Virginia was a much more mobile and unruly society.

In contrast to the Southeast, it was much more difficult for native peoples of New England to resist the encroaching English colonists. For one thing, the Northeast was much less densely populated. Epidemic diseases introduced by European fishermen and fur traders reduced the population of New England’s coastal Indians about ninety percent by the early 1620s. Further, this area was fragmented politically into autonomous villages with a long history of bitter tribal rivalries. Such factors allowed the Puritans to expand rapidly across New England.

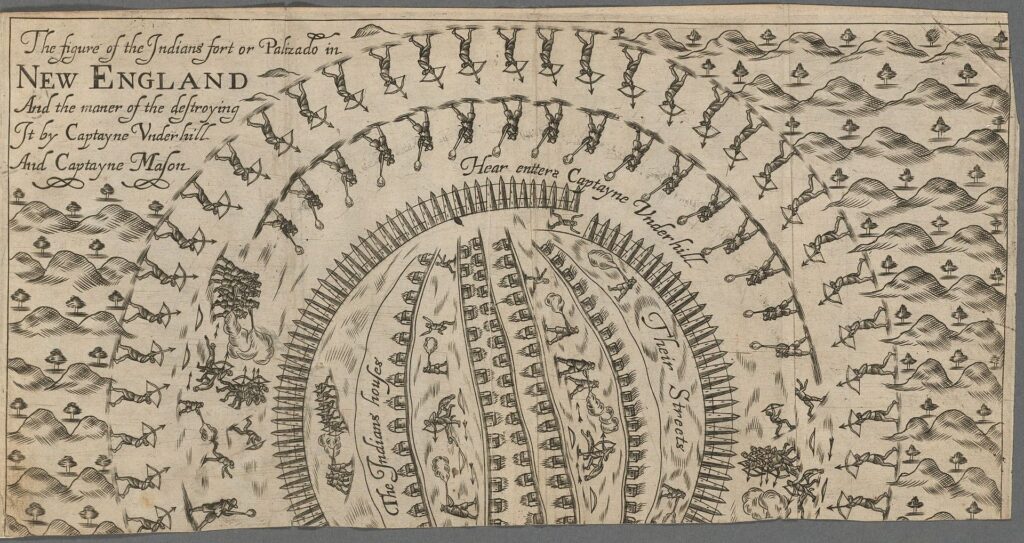

Some groups, notably the Massachusetts, whose number had fallen from about 20,000 to just 750 in 1631, allied with the Puritans and agreed to convert to Christianity in exchange for military protection. But the migration of Puritan colonists into western Massachusetts and Connecticut during the 1630s provoked bitter warfare, especially with the Pequots, the area’s most powerful people. In 1636, English settlers accused a Pequot of attacking ships and murdering several sailors; in revenge, they burned a Pequot settlement on what is now Block Island, Rhode Island. Pequot raids left about thirty colonists dead. A combined force of Puritans and Narragansett and Mohegan Indians retaliated by surrounding and setting fire to the main Pequot village on the Mystic River.

In his History of Plymouth Plantation, William Bradford described the destruction by fire of the Pequot’s major village, in which at least 300 Indians were burned to death: “Those that escaped from the fire were slain with the sword; some hewed to pieces, others run through with their rapiers [swords]…. It was a fearful sight to see them thus frying in the fire, and the streams of blood quenching the same.” The survivors were enslaved and shipped to the Caribbean. Altogether about 800 of 3,500 Pequot were killed during the Pequot War. In his epic novel Moby Dick, Herman Melville names his doomed whaling ship “The Pequod,” a clear reference to earlier events in New England.

From Puritan to Yankee

In his autobiography, the Boston-born Benjamin Franklin, the son of a Puritan, described how he, as a young man, had embarked on a “bold and arduous project of arriving at moral perfection.” He explained that he “wished to live without committing any fault at any time…,” and identified thirteen steps toward moral perfection:

1. Temperance: Eat not to dullness; drink not to elevation.

2. Silence: Speak not but what may benefit others or yourself; avoid trifling conversation.

3. Order: Let all your things have their places; let each part of your business have its time.

4. Resolution: Resolve to perform what you ought; perform without fail what you resolve.

5. Frugality: Make no expense but to do good to others or yourself, i.e., waste nothing.

6. Industry: Lose no time; be always employed in something useful; cut off all unnecessary actions.

7. Sincerity: Use no hurtful deceit; think innocently and justly, and, if you speak, speak accordingly.

8. Justice: Wrong none by doing injuries or omitting the benefits that are your duty.

9. Moderation: Avoid extremes; forbear resenting injuries so much as you think they deserve.

10. Cleanliness: Tolerate no uncleanliness in body, clothes, or habitation.

11. Tranquillity: Be not disturbed at trifles, or at accidents common or unavoidable.

12. Chastity: Rarely use venery but for health or offspring, never to dullness, weakness, or the injury of your own or another’s peace or reputation.

13. Humility: Imitate Jesus and Socrates.

Franklin would come to symbolize a set of values very different from those of the seventeenth-century Puritans. He was striving, ambitious, and determined to get ahead in life. For many early nineteenth-century Americans, he would come to embody the go-getting Yankee.

If the Puritans who settled in New England in the seventeenth century could see themselves a hundred years later, they would be amazed. Their value system had been transformed. Puritans had become Yankees.

How Had This Transformation Taken Place?

An older view treated the history of New England as the triumph of rationality, tolerance, and Enlightenment over superstition, parochialism, and reactionary Calvinism. The prime symbol of Puritan intolerance was the Salem witch scare, in which nineteen women and men were hanged and one (who refused to plead guilty or not guilty) was crushed to death. The heroes of this older version of history were individuals like Anne Hutchinson and Roger Williams who rebelled against the Puritan leadership.

An early twentieth-century German sociologist offered another explanation of how Puritans became Yankees. Max Weber argued that Puritans became Yankees because of ideas implicit in Puritan dogma. According to Weber, the Catholic religion was well suited to an economically stagnant world. Monks, nuns, and friars lived in idleness and did not contribute to national wealth. Because the clergy did not marry, they also failed to contribute to population growth. Expenditures on churches and pilgrimages made it difficult to accumulate capital for investment. The clergy lived on the alms of the poor, making it difficult for poor people to improve their economic position.

Protestantism, Weber argued, was well-suited to capitalism and economic growth, and Puritanism represented the most extreme form of Protestantism. For the Puritans, wealth was not ethically bad. Idleness and sinful enjoyment, not wealth, were bad. God had given each person a calling, and the accumulation of wealth was a sign that one was fulfilling one’s calling.

Also, according to Weber, Puritanism promoted individualism. The Puritans had no saints, no priests, no holy relics. There were only individuals and their conscience. It is not an accident that Puritans were among the very first people to keep diaries—an account of their inner thoughts—and write love letters and the first novels.

So how, then, do we get from the world of the early Puritans to a very different world a century later? For simplicity’s sake, we might identify three key developments: the pressures of a growing capitalistic economy; deepening religious divisions; and the pressures exerted by a centralizing British empire.

At first, New England’s economy was highly dependent on credit from London merchants. New Englanders raised cattle and grew corn, but the colonists were chronically poor. Then in 1637 credit stopped as England moved toward civil war. New Englanders had to find new means of making a livelihood, and part of the answer was fishing to meet an enormous demand for fish from Catholic Europe. Cod fishing led New England into shipbuilding and trade, especially with the West Indies. New Englanders began to distill West Indian molasses into rum.

The result of economic growth was to destroy the carefully arranged social hierarchy that the New England Puritans had tried to establish, a hierarchy based on age, status, and family. The Puritans had enacted sumptuary laws that prescribed what clothing and adornments each rank in society might wear, but such laws proved increasingly difficult to enforce.

The ready availability of land further undermined social hierarchy. Unlike England, where land ownership was associated with social privilege, in New England land was a commodity for speculation.

At the same time, New England witnessed a breakdown in religious unity. Over time, church membership fell, and ministers were faced with the dilemma about how to fill their pews. Some began to alter their membership rules. Instead of confining membership to individuals who had gone through a conversion experience, some ministers allows the children of church members to automatically join the church.

Meanwhile, new notions of science and psychology brought into question the Puritans’ beliefs in human depravity and divine omnipotence. Then, in the early 1690s, the Salem witch scare threw into question Puritan morality.

Podcast

Childbirth in Early America

Listen to the podcast, “Childbirth in Early America”.

Dimensions of Change in Colonial New England

Although most of New England’s settlers were Puritans, these people did not agree about religious doctrine. Some, like the Pilgrims of Plymouth, believed that the Church of England should be renounced, while others, like Massachusetts Bay’s leaders, felt that the English church could be reformed. Other issues that divided Puritans involved who could be admitted to church membership, who could be baptized, and who could take communion.

Disagreements over religious beliefs led to the formation of a number of new colonies. In 1636, Thomas Hooker (1586-1647), a Cambridge, Massachusetts minister, established the first English settlement in Connecticut. Convinced that government should rest on free consent, he extended voting rights beyond church members. Two years later, another Massachusetts group founded New Haven colony in order to combat moral laxness by setting strict standards for church membership and basing its laws on the Old Testament. This colony was incorporated by Connecticut in 1662.

In 1635, Massachusetts Bay colony banished Roger Williams (1604-1683), a Salem minister, for claiming that the civil government had no right to force people to worship in a particular way. Williams had even rejected the ideal that civil authorities could compel observance of the Sabbath. Equally troubling, he argued that Massachusetts’s royal charter did not justify taking Indian land. Instead, Williams argued, the colonists had to negotiate fair treaties and pay for the land. Instead of returning to England, Williams headed toward the Narragansett Bay, where he founded Providence, which later became the capital of Rhode Island. From 1654 to 1657, Williams was president of Rhode Island colony.

As New England expanded, its economy became increasingly oriented toward commerce and trade. Older Puritan ideas that were highly critical of commerce began to fade.

The New England Puritans, like many Americans before the nineteenth century, rejected the idea that prices should fluctuate freely according to the laws of supply and demand. Instead, they believed that there was a just wage for every trade and a just price for every good. Charging more than this just amount was “oppression,” and authorities sought by law to prevent prices or wages from rising above a customary level.

Yet within a few decades of settlement, the Puritan blueprint of an organic, close-knit community, a stable, self-sufficient economy, and a carefully calibrated social hierarchy began to fray as New England became increasingly integrated into the Atlantic economy. To try to maintain traditional social distinctions, Massachusetts Bay colony in 1651 adopted a sumptuary law, which spelled out which persons could wear certain articles of clothing and jewelry.

But as early as the second half of the seventeenth century, a growing number of New Englanders were engaged in an intricate system of Atlantic commerce, selling fish, furs, and timber not only in England but throughout Catholic Europe, investing in shipbuilding, and transporting tobacco, wine, sugar, and slaves. Particularly important was trade with the West Indies and the Atlantic islands off of northwestern Africa. Such trade was highly competitive and risky, but over time it gradually created distinct classes of merchants, tradesmen, and commercially-oriented farmers.

As New England’s economy grew, the region’s Indians peoples found their way of life threatened.

For nearly half a century following the Pequot War, New England was free of major Indian wars. During this period, the region’s indigenous people declined rapidly in numbers and suffered severe losses of land and cultural independence. During the first three-quarters of the seventeenth century, New England’s indigenous population fell from 140,000 to 10,000, while the English population grew to 50,000. Meanwhile, the New England Puritans launched a concerted campaign to convert the native population to Protestantism. John Eliot, New England’s leading missionary, convinced about 2,000 to live in “praying towns,” where they were expected to adopt white customs. New England Indians were also forced to accept the legal authority of colonial courts.

Faced with death, disease, and cultural disintegration, many of New England’s native peoples decided to strike back. In 1675, the chief of the Pokanokets, Metacomet (whom the English called King Philip), forged a military alliance including about two-thirds of the region’s Indians. In 1675, he led an attack on Swansea, Massachusetts. Over the next year, both sides raided villages and killed hundreds of victims. Twelve out of ninety New England towns were destroyed.

The last major Indian war in New England, King Philip’s War, was the most destructive conflict, relative to the size of the population in American history. Five percent of New England’s population was killed–a higher proportion than Germany, Britain, or the United States lost during World War II. Indian casualties were far higher; perhaps 40 percent of New England’s Indian population was killed or fled the region. When the war was over, the power of New England’s Indians was broken. The region’s remaining Indians would live in small, scattered communities, serving as the colonists’ servants, slaves, and tenants.