Introduction: The Colonial Era

William Shakespeare’s England

William Shakespeare was alive when England established its first North American colonies. We often hear that Shakespeare speaks to our time. One book, entitled Shakespeare, Our Contemporary, emphasizes the analogies between Shakespeare’s plays and the issues of modern life, from teenage suicide in Romeo and Juliet to racial prejudice in Othello, anti-Semitism in The Merchant of Venice, and imperialism in The Tempest.

In fact, Shakespeare did not live in anything resembling a modern country. His England was, in many respects, poor and backward.

What, then, was England like during his lifetime?

The English historian Keith Thomas has described conditions in Shakepeare’s England, No one ate fresh meat during the winter. The English ate scarcely any vegetables, and no chocolate or sugar. Potatoes had not yet been introduced into England. Nor did the English drink tea, coffee, gin, or port.

The modern arrangement of meals—breakfast, lunch, and dinner—had not yet been invented.

The English had no spoons, no forks, no glasses, and no china. Nor, did they have hot or cold running water.

They took no baths and had no handkerchiefs to blow their noses into, nor mirrors in which to gaze at themselves.

The English wore no calico, linen, or silk. The modern male costume—a suit coat, waistcoat (or vest), and trousers—did not yet exist.

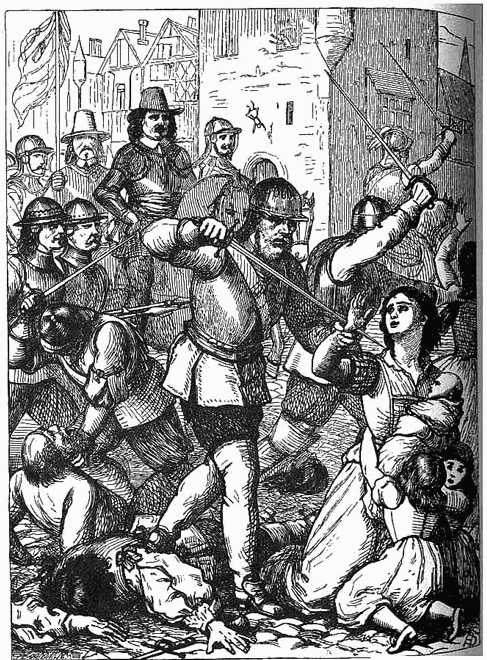

Heretics and witches were still burned at the stake during Shakespeare’s lifetime. Prisoners were still punished by torture.

Shakespeare’s England was, in many respects, a small, relatively backward, poor and underdeveloped country. The population was, as historian Keith Thomas observed, sparse, totaling no more than three million people, concentrated overwhelmingly in rural villages and hamlets, though some 300,000 people lived in London.

Inequality was extreme. Shakespeare’s England was an agricultural society, but more than half the people were without land. Poverty was widespread. Half the population suffered chronic unemployment and lived at a subsistence level. Well-being depended on the fate of the harvest, but one harvest in six failed.

Life was, in the famous words of the philosopher Thomas Hobbes who lived half a century after Shakespeare, nasty, brutish and short. At birth, the life expectancy of a noble was 29.6 years. A third of the children of aristocrats died before the age of five. Death rates in London were particularly bad, when 30 of every 100 children died by the age of six, 60 by the age of sixteen. Shakespeare’s was a world colored by pain, sickness, and premature death.

Peoples’ diet lacked sufficient vitamins A, D, and iron and, as a result, many people experienced eye problems, rickets, anemia, and urinary infections. Tuberculosis ran rampant, as did dysentery. Epidemics—from flu, typhus, and smallpox—caused thousands of deaths. About one person in six had their face riddled with pox marks.

The worst of all the epidemics was bubonic plague, still so common that a children’s nursery rhyme described the symptoms:

Ring around the rosie, Pockets full of posies, Ashes, ashes, we all fall down.

In the 150 years before 1665, London was free of plague just twelve years. The year Hamlet was first performed, 36,000 people in London died of plague, one-sixth of the city’s population. In 1625, another sixth of London’s population died. In 1665, 68,000 people died of plague.

There was no hope in turning to doctors for help, historian Keith Thomas pointed out. There were only thirty-eight in Shakespeare’s London, and their treatments were largely confined to bloodletting or the application of leeches, without antiseptics or anesthesia. Indeed, medical practice, killing cats and dogs, actually worsened the risk of plague. Lacking any effective treatment, doctors recommended various amulets made of arsenic, mercury, or tobacco.

People were also exceedingly vulnerable to fire. Houses had thatched roofs and chimneys were often made of wood. Lacking matches, people relied on burning coals and candles. The result: frequent fires. The Great Fire of London in 1666 destroyed 13,000 houses and left 100,000 people homeless. Nine years later, a royal palace was destroyed by a fire touched off by an indoor charcoal fire. Nor were there effective methods for putting out fires, since there was no reliable water supply and no fire engines capable of projecting streams of water. There was also no fire insurance. All victims could do was apply for a collection in church.

People were at the mercy of the weather, fire, disease, famine, and epidemics.

How did people cope in a society marked by poverty, illness, premature death, and sudden disaster? Drinking alcohol was one response. On average, the English drank about three pints of beer a day, plus hard cider, wine, and other spirits. Smoking tobacco was a new way that people deal with life’s stresses.

Shakespeare’s world was fraught with anxiety. During Queen Elizabeth I’s lifetime, Protestant England was locked in a prolonged religious struggle with Catholic Spain, culminating in a failed attempt to invade England by sea in 1588. The defeat of the Spanish armada, however, did not end religious tensions. There were attempts to assassinate the monarch, and in 1605, a group of conspirators attempted to blow up the houses of Parliament. The plot was disrupted when Guy Fawkes, one of the conspirators, was discovered with thirty-six barrels of gunpowder.

Alongside the profound political upheavals of the era were far-reaching economic, religious, social and intellectual disruptions.

There were bitter conflicts over values during Shakespeare’s lifetime, associated with the rise of a religious movement known as Puritanism and the spread of scientific rationalism. The Puritans were the more radical Protestants who wanted to purify the English church by ridding it of elements not rooted in Scripture. The Puritans brought a distinctive sensibility to public life: an outlook that was solemn, morally austere and repulsed by the life of the body or the blurring of gender roles.

Political tensions were intense, too. One issue involved royal succession, as Queen Elizabeth I, the Virgin Queen, left no heir. This was followed by repeated conflicts between Parliament and the English Crown over royal authority, intensified by conflicts involving Scotland and Ireland, resulting in the execution of King Charles I and what is known as the English Civil War, a series of conflicts that raged from 1642 to 1651. All told, the Civil War led to some 85,000 combat deaths in England and Wales, 127,000 non-combat deaths, with another 15,000 dead in Scotland, and 137,000 deaths in Ireland.

Another source of tension involved a bloody and costly struggle in Ireland. England succeeded in conquering Ireland during Elizabeth I’s reign, and proceeded to implement a policy known as “plantation settlement”—dispossessing Irish landholders of their land and granting their land to Englishmen and Scots. A massive rebellion by Irish Catholics against English rule erupted in 1641 and was not defeated until 1652, when the English deported some 50,000 Irish as indentured servants and slaves.

These years also saw the beginning of the Scientific Revolution in England, with its emphasis on empiricism, observation, experimentation, and mathematical reasoning. The Scientific Revolution also threw into question many earlier values. In 1611 the English poet, John Donne, wrote:

[The] new Philosophy calls all in doubt,

The Element of fire is quite put out;

The Sun is lost, and th’earth, and no man’s wit

Can well direct him where to look for it.

Shakespeare lived at a critical juncture in England’s history. The challenges were economic as well as demographic, intellectual, political, and religious. During Shakespeare’s lifetime, the economy experienced intense dislocations as a result of the introduction of capitalist agriculture and rapid population growth.

Around the time of Shakespeare’s birth in 1564, England had only begun to treat land as something that could be bought and sold, that is, as private property. Rents for land rose sharply after 1580, climbing 30 or 40 percent over the value a few decades before. One reason for the rise in rents was a process known as enclosure. Lands that had traditionally been under common ownership were gradually expropriated by landlords and used for pasture.

At first glance, the amount of land enclosed seems small, about five percent of the cultivatable land in England. But the process of enclosure radically altered the status of people who had supported themselves using common lands. Many were driven from the soil and transformed into wage earners and others migrated from the countryside into towns. One result was a rash of peasant revolts.

In a famous 1516 book Utopia, Sir Thomas More blamed enclosure for a sharp increase in crime:

But I do not think that this necessity of stealing arises only from hence; there is another cause of it, more peculiar to England. “What is that?” said the Cardinal. “The increase of pasture,” said I, “by which your sheep, which are naturally mild, and easily kept in order, may be said now to devour men and unpeople, not only villages, but towns…

But I do not think that this necessity of stealing arises only from hence; there is another cause of it, more peculiar to England. “What is that?” said the Cardinal. “The increase of pasture,” said I, “by which your sheep, which are naturally mild, and easily kept in order, may be said now to devour men and unpeople, not only villages, but towns…”

To overcome the problems of unemployment, poverty, crime and social unrest, England adopted a set of policies later known as mercantilism. The American historian Edmund Morgan has described the distinctive features of mercantilism. Mercantilism emphasized state direction of all economic activities to maximize the state’s economic welfare rather than private profits. A system of state economic control, mercantilism regulated wages and migration, prohibited begging, established a system of alms for the aged and infirm, and put the poor to work.

Here, it is important to emphasize that England’s government in Shakespeare’s times was far different than it is today. Not many people had a hand in government. In 1603, the nobility numbered fifty-five. A somewhat larger group of landowners also had a hand in government, amounting to about five percent of the adult male population. Altogether, about 15 percent of the adult male population elected representatives to Parliament.

The major concern of government was to keep the English population working. A statute passed in 1563 required laborers to work from five in the morning to seven or eight at night from mid-March to mid-September, and during the remaining months from daybreak to nightfall. Time out for eating, drinking, and rest was not to exceed two-and-a-half hours a day.

One part of the population was, of course, not expected to comply with these rules: gentlemen. But even for those who wanted to work full-time, this was often not possible.

In spite of the myth of dawn to dusk toil, milking cows, digging ditches, and thatching roofs, there were many times when even the most industrious farmer was idle. Bad weather might halt farm work. The best estimate was that farmers were idle about half the time.

Meanwhile, about half the English population led a hand-to-mouth existence. It was a life of frequent hunger and malnutrition, but a life that did not require much work. These people might tend a little garden of an acre or two, and supplement their diet with roots, nuts, and berries. But unlike the American Indians, commoners were not permitted to hunt to supplement their diet. Hunting was reserved for landowners.

The poor were not in good repute with England’s elite. During Shakespeare’s lifetime, the number of poor people grew far faster than the number of jobs for them. Many eked out a living in the woods; some turned to crime.

England’s rulers imposed a remarkable solution: they decided to ration work. No young man was permitted to practice a trade until he had served an apprenticeship. Even then, if he was not yet 30 and married, he still could not work for himself.

Employers were allowed to hire labor only by the year, not by the week, day, or hour. The intention was to ensure that all workers were supervised by a master and to force masters to hire as maximize employment. Hiring by the year meant that laborers did not have to work hard to keep their jobs.

England’s leaders were eager to force the poor to contribute to the nation’s wealth and to keep them working so that they would not rebel. The alternative—to create financial incentives to encourage the poor to work—did not occur to anyone. As one observer put it, “Everyone but an idiot knows that the lower classes must be kept poor, or they will never be industrious.”

The result was just the opposite of what England’s elite intended. Idleness was encouraged and workers were discouraged from working hard.

In response, in 1576, England’s leaders began to place beggars into workhouses and Houses of Correction, where they were forced to make thread and yarn, receiving nothing but room and board for their efforts. In 1697, paupers were required to wear red or blue Ps on their right hand shoulder to set them apart. Many of these paupers would be shipped off to New World colonies to contribute to the nation’s wealth there. The English poor were flogged, branded, and forced to work.

Mercantilism was an economic philosophy that sought to ensure that even the criminal and the poor would contribute to the national wealth. It was a set of policies designed to promote national development.

Mercantilism stressed the necessity of state control of the economy in order to develop agriculture, manufacturing, and foreign trade. Skilled foreigners were brought to England to produce goods, like draperies, that the English did not know how to make. Mercantilism also rejected the notion of unbridled economic competition. The government licensed monopolies for many goods: making paper, printing the laws of England, even printing the Psalms of David.

Today, England’s response to economic backwardness sounds irrational: rationing jobs, fixing wages and prices, subsidizing industries, and regulating production. The first person to point out the absurdity was a Scottish economist and moral philosopher named Adam Smith. In 1776, he published the most devastating attack on an economic philosophy ever written. He called his book The Wealth of Nations. Mercantilism, Smith charged, was a system of special interest and privilege that stifled individual initiative and encouraged people to work as little as possible. Smith argued that if individuals were free to pursue their own self-interest, there would be a higher standard of living for all. In his most famous phrase, he wrote: “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.”

The American colonies would provide a test case for Smith’s thesis. Unbridled self-interest would, over time, create one of the wealthiest societies on the face of the earth. But the accumulation of wealth co-existed with indentured servitude, the growth of slavery, and the displacement of Indians from their homelands.