Forging a Distinct American Identity

Forecasting the Future

Forging a Distinctly American Identity

A sense of a distinctive American identity arose slowly and did not truly coalesce until the end of the American Revolution. In part, a common American identity arose out of a growing recognition of the significant ways that the colonies differed from the mother country. These included the absence of a titled nobility or rigid class lines reflected in accents and dress.

Then, too, there were a series of developments that helped fuel a sense of Americanness. There was a population growth rate far faster than England’s. By the beginning of the eighteenth century, the population in Britain’s North American colonies was growing at an unprecedented rate. At a time when Europe’s population was increasing just one percent a year, New England’s growth rate was 2.6 or 2.7 percent annually. By the early-eighteenth century, the population was also growing extremely rapidly in the middle Atlantic and southern colonies, largely as a result of a low death rate and a sex ratio that was more balanced than in Europe itself. All told, the American population would double every twenty to twenty-five years, which is among the fastest growth rates in world history.

By 1700, Britain’s North American colonies also offered an unprecedented degree of social equality and political liberty for white men. The colonies differed from England itself in the proportion of white men who owned property and were able to vote.

A common sense of identity was also nurtured by repeated conflicts with North America’s indigenous peoples, the French, and the Spanish. Warfare took place almost constantly from the time of settlement to the end of the Seven Years War in the mid-eighteenth century. Roughly forty percent of the white male population participated in these conflicts, helping instill a sense of collective identity.

Further contributing to a common American identity was the shared experience of colonial expansion, which involved the displacement of the indigenous population, and the shared dependence on various forms of unfree labor, of which the most rapidly growing form consisted of Black slaves, who could be found in every one of Britain’s North American colonies.

Ethnic and religious diversity was another characteristic that distinguished the colonies from England. The early and mid-eighteenth century brought far-reaching changes to the colonies, including a massive immigration, especially of the Scots-Irish; the forced importation of tens of thousands of enslaved Africans; and increasing economic stratification in both the northern and southern colonies.

A religious event known as the Great Awakening also instilled a sense of distinctive American identity. A series of religious revivals spread across all of England’s North American colonies beginning in the 1730s. Public burnings were held of wigs, cloaks, rings, and sometimes even books. . The most important religious event of the colonial era, the Great Awakening represented a reaction against spiritual sloth and the growing commercialization of society.

The greatest theologian of the Great Awakening, Jonathan Edwards, sought to restore the values and beliefs of the early Puritans. He declared that “children, who are unconverted…are going down to hell” and that even “the greatest earthly potentates in their greatest majesty and strength…are but feeble, despicable worms of the dust, in comparison of the great and almighty Creator…”

The Great Awakening helped forge a sense of American identity stretching across all the North American colonies. It also instilled a sense that God works directly through the people, not through churches or preachers or monarchs. In addition, the Great Awakening fostered a sense that the colonists lived at a time of ferment and possibility, when Christ’s Second Coming was growing near and that the time was drawing closer when God’s kingdom on earth would be established. The Great Awakening helped to establish the psychological preconditions for the American Revolution.

Yet another contributor to the growth of an American identity was England’s repeated efforts between 1660 and 1760 to centralize control over its New World Empire and impose a series of imperial laws upon its American colonies. By the 1760s—after Britain had decisively defeated the French in what is known in America as the French and Indian War and in Europe as the Seven Years War—the colonists were in a position to challenge their subordinate position within the British Empire.

History Through…

… Primary Sources

In recent years, there has been a tendency for school districts to downplay the importance of early American history. Many districts relegate American history prior to 1877 to elementary school or to the earliest years of middle school. Early American history is simply seen as a collection of stories, legends, and myths suited only for young minds.

In fact, the colonial period is truly this country’s formative period. Many of this society’s fundamental principles were planted in the colonial period—such as our commitment to freedom of religion, representative government, liberty, and equality. But the colonial period also left American society with less positive legacies, such as the institution of slavery and a long history of conflict with North America’s indigenous population.

History Through…

… Primary Sources: American Conceptions of Liberty.

The social history of eighteenth-century America presents a fundamental paradox. In certain respects, colonial society was becoming more like English society. The power of royal governors was increasing, social distinctions were hardening, lawyers were paying more attention to English law, and a more distinct social and political elite gradually emerged, as a result of the expansion of Atlantic commerce, the growth of the tobacco and rice economies, and especially the sale of land. To be sure, compared to the English aristocracy, the wealthiest merchants, planters, and landholders were much more limited in wealth and less stable in membership. Nevertheless, there was the growth of regional elites, which intermarried, aped English manners, and dominated the highest levels of colonial government.

Yet the eighteenth century also witnessed growing claims of “English liberties” against all forms of tyranny. A 1705 legal case pitting Governor Joseph Dudley of Massachusetts against two cart drivers, whom the governor charged with insubordination, offers a vivid example of the mounting challenges to social deference. This case became a landmark in limiting the authority of public officials.

Joseph Dudley to Massachusetts Superior Court Justices, January 23, 1705

Account of Governor Joseph Dudley:

The Governour informs the Queens Officers of her majestys Superior Court that on Friday the seventh of December last past he took his journey from Roxbury towards new hampshire and the Province of mayn for his her majestys immediate service there….[He] had not proceeded above a mile from hojme before he mett two carts in ye Road Loaden with wood, of which ye Carters were as he is since informed Winchester and Trobridge.

The Charet wherein the Governour was had three sitters and their Servants…drawn by four horses, one very unruly, & was attended only at that instant by Mr. William Dudley, the Governour[‘]s son.

When the Governour saw the two carts approaching he directed his son to bid them to give him the way having a Difficult drift with four horses & a tender Charet so heavily loaden not fitt to break the way, Who accordingly did Ride up & told them the Gov[erno]r was there, & they must give way, immediately upon it the second Charter came up to ye first…& one of them says aloud he would not goe out of the way for ye Governour whereup the Gov[erno]r came out of ye Charet and told Winchester he must give way to ye Charet. Winchester answered boldly…I am as good flesh & blood as you. I will not give way you may goe out of the way & came towards the Governour. Whereupon the Governour drew his sword to secure himself & command the Road & went forward; yet without either saying or intending to hurt ye carters or once pointing or passing at them but justly supposing they would obey & give him the way; and again commanded them to give way. Winchester answered that he was a Christian & would not give way & as the Governour came toward him he advanced & at len[g]th layd hold on the Gov[erno]r & broke the sword in his hands. Very soon after came a Justice of the Peace, & sent the Carters to prison…the Gov[erno]r demanded their names which they would not say…nor did they once in the Gov[erno]r[‘]s heraring or sight pull of[f] their hatts…or any word to excuse the matter but absoltuely stood…on each side of the forehorse laboured & put forward to drive upon and over the Governour. And this is averred upon the honour of ye Governorous.

Account of Thomas Trowbridge:

I passed through the town of Roxbury in the lane between the hosue of Ebenezer Davis and the widow Pierpons in which lane are two plaine cart paths which meet in one at the de[s]cent of the hill. I being…on the west sideof hte land I seeing the Governor[‘]s coach where the paths meet in one…drave leisurely so that the coach might take that path one the east side…which was the best…when I came near the paths met I made a astop thinking they would pass by me in the other…And the Governor[‘]s son…biding that it was easier for the coach to take the other path than for me to turn out of that; then did he strike my horse and…drew his sword and told me he would stab one of my horses. I stept betwixt him and my horses and told him he should not if I could help it, he…made several passes at me with his sword which I fended of[f] with my stick. Then came up John Winchester of Muddyriver alias Brookline…who gives the following account.

…I left my cart and came up and laid down my whip by Trowbridge his Team. I asked Mr. Wm. Dudley why he was so rash he replyed this dog wont turn out of the way for the Governour. Then I passed to the Governour with my hat under my arm hopeing to moderate hte matter saying may it pleas[e] your Exelency it is very easie for you to take into this path…he answered…you rouge or rascall I will have that way. I then told his exelency if he would but have patience a minute or two I would clear that way for him. I turning about and seeing Trowbridge his horses twisting about ran to stop them…the Governour followed me with his drawn sword and said run the dogs thro and with his naked sword stabbed me in the back. I faceing about he struck me on the head…giveing me there a bloody wound. I then expecting to be killed dead on the spot to prevent his Exelency from such a bloody act in the heat of his passion I catcht hold on his sword and it broke but yet…in his furious rate he struck me divers blows with the hilt and piece of hte sword remaining…I called to the standers by to take notice that what I did in defense of my life…the Governour said you lie you dog you lie you Divell…Then said I such words dont become a christian his Exelency replyed a christian you dog a christian you Divell…I was a chrsitian before your were born.

I Thomas Trowbridge further declare that…the Governour struck me divers blows then takeing Winchesters driveing stick and with the great end there of struck me severall blows as he had done to Winchester afore. Winchester told his Exlency he had bene a true subject to him and served him and had honoured him…his Exelency said…you shall goe to Goale you dogs; then twas askt what should become of our teams his Excellency said let them sink into the bottom of the earth.

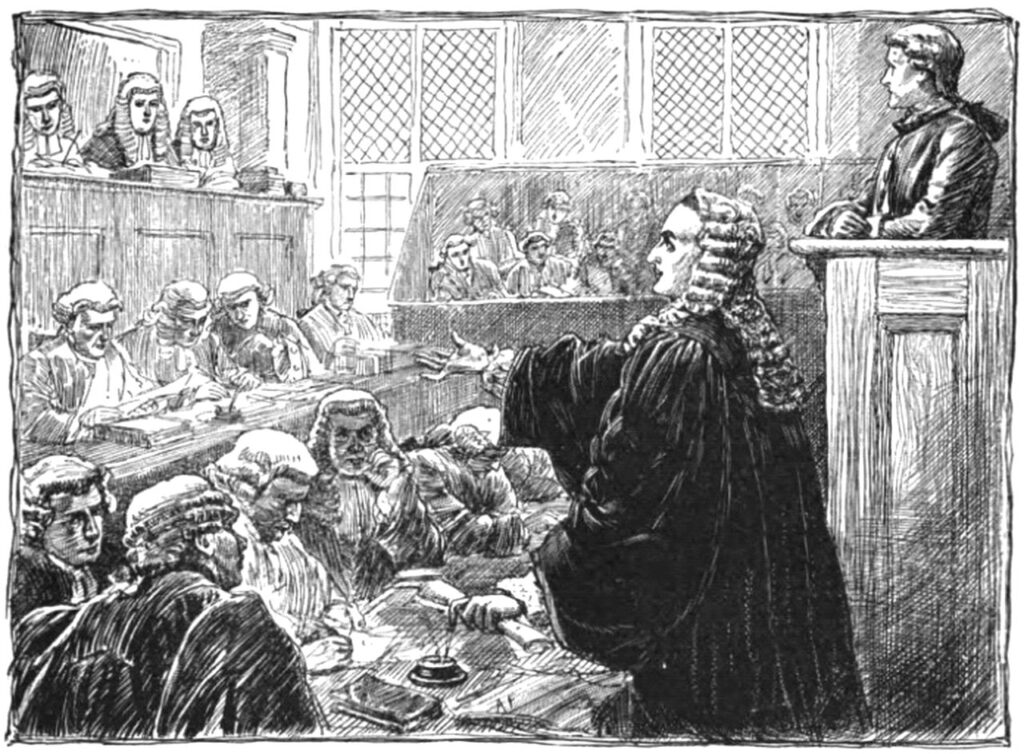

The Zenger Case and the Freedom of Press

A pivotal jury decision in New York in 1735 helped establish the principle of freedom of the press. Opponents of New York’s royal governor, William Cosby, had set up John Peter Zenger (1697-1746), a German immigrant, as publisher of the New York Weekly Journal in 1733. The next year, after New York’s governor dismissed one of his leading opponents, Chief Justice Lewis Morris, from office, the Weekly Journal severely criticized Cosby. Because the articles attacking Cosby were published anonymously, the governor had Zenger indicted and tried for seditious libel. English law defined any criticism of a public official—true or false—as libel. But Zenger’s attorney, Andrew Hamilton of Philadelphia, persuaded the jury that Zenger had printed the truth and that the truth is not libelous.

In stirring words, Hamilton told the jury that “the Question before the Court…is not the Cause of a poor Printer, nor of New-York alone…. No! It may in its Consequence, affect every Freeman that lives under a British Government on the Main of America…. It is the Cause of Liberty….Every Man who prefers Freedom to a Life of Slavery will bless and honour Your, as Men who have…given us a Right,—the Liberty—both of exposing and opposing arbitrary Power (in these Pars of the World, at least) by speaking and writing Truth.”

John P. Zenger, New York Weekly Journal, Number XIX, March 11, 1733

Mr. Zenger,

Pray incert the following sentiments of Cato, and you’ll oblige Yours, &c.

Considering what sort of a Creature Man is, it is scarce possible to put him under too many restraints, when he is possessed of great Power: He may possibly use it well; but they act most prudently, who supposing that he would use it ill incluse him within certain Bounds and make it terrible to him to exceed them.

It is nothing strange, that Men, who think themselves unaccountable, should act unaccountably, and that all Men would be unaccountable if they could; even those who have done nothing to displease, do not know but sometime or other they may; and no Man cares to be at the intire Mercy of another. Hence it is that if every Man had his Will, all Men would exercise Dominion, and no Man would suffer it. It is therefore owning more to the Necessities of Men, than to their Inclinations, that they have put themselves under the Restraint of Laws, and appointed certain persons, called Magistrates, to execute them; otherwise they would never be executed, scarce any Man having such a Degree of Virtue as unwillingly to execute the Laws upon himself; but on the contrary, most Men, thinking them a Grievance, when they come to medle with themsleves and their Property.

Hence grew the Necessity of Government, which was the mutual Contract of a Number of Men, agreeing upon certain Terms of Union and Society, and putitng htemselves under Penalties if they vilated these terms, which were called Laws, and put into the Hands of one or more Men to execute. And thus men quitted Part of their natural Liberty to acqurie civil Security. But frequently the Remedy prov’d worse than the Disease; and humane Society had often no enemies so great as their own Magistrates; who, wherever they were trusted with too muc Power, always abused it, and grew mischievous to those who made them what they were. Rome, while she was free, (that is, while she keept her Magistrates within due bounds) could defend herself against all the world, and conquer it; but being enslaved (that is her Magistrates having broke their Bounds) she could not defend her self against her own single Tyrants; nor could they defend her against her foreign Foes and Invaders: For by their Madness and Cruelties they had destroyed her Virtue and Spirit, and exhausted her Strength. This shews that those Magistrates, that are at absolute difference with a Nation, either cannot subsist long, or will not suffer the Nation to subsist long; and that mighty Traitors, rather than fall them selves, will pull down their Country.

The common People generally think that great Men have great Minds, and scorn base Actions; which Judgment is so false, that the basest and worst o fall Actions ahve been done by great Men; perhaps they have not picked private Pockkets, but they have done worse, they have often disturbed, deceived and pillaged the World: And he who is capable of the hghest Mischiefs, is capable of the Meanest. He who plunders a Country of Millions of Money, would in suitable Circumstances steal a Silver Spoon; and a Conqueror, who steals and pillages a Kingdom, would in an humbler Fortune rifle a Portmanteau or rob an Orchard.

To Conclude: Power without Control appertins to God alone; and no Man ought to be trusted with what no Man is equal to. In Truth, there are so many passions and Inconsistencies, and so much Selfishness, belonging to humane Nature, that we can scarce be too much upon our Guard against each other. The only Security we have that men will be Honest, is to make it their Interest to be Honest; and the best Defence we can have against their being Knaves, is to make it terrible to them to be Knaves. As there are many Men, wicked in some Stations, who would be innocent in others; the best way is to make Wickedness unsafe in any Station.