Contrasting Forms of English Colonization

Hidden History

The American Paradox: Freedom and Slavery

English colonization of the Southern colonies, like the settlement of the Caribbean, depended on various forms of unfree labor. Initially, white indentured servants constituted the primary labor force, to be later replaced by black slaves. This presents us with a paradox, a paradox that is central to American history: Why is it that the wealth of some of America’s strongest exponents of liberty and equality depended on forced labor?

Americans revolted in 1776 to escape what they called the tyrannies of British rule. Yet many of the leading revolutionaries who so boldly declared their dedication to liberty and equality supported themselves through a labor system, slavery, which was more oppressive than any act of the British government.

How is it possible to reconcile the dedication of liberty of such Virginians as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison with the fact that their wealth rested on slavery? Were they simply hypocrites?

To understand the connection between slavery and the founders’ dedication to liberty, it is necessary to look at the history of England’s largest North American colony, Virginia.

Slavery Takes Root in Colonial Virginia

Black slavery took root in the American colonies slowly. It seems plausible that small numbers of Africans lived in Virginia before 1619, the year a Dutch ship sold some twenty blacks (probably from the West Indies) to the colonists. But it was not until the 1680s that black slavery became the dominant labor system on plantations there. As late as 1640, there were probably only 150 blacks in Virginia and in 1650, 300. But by 1680, the number had risen to 3,000 and by 1704, to 10,000.

Until the mid-1660s, the number of white indentured servants was sufficient to meet the labor needs of Virginia and Maryland. Then, in the mid-1660s, the supply of white servants fell sharply. Many factors contributed to the growing shortage of servants. The English birth rate had begun to fall and with fewer workers competing for jobs, wages in England rose. The great fire that burned much of London in 1666 created a great need for labor to rebuild the city. Meanwhile, Virginia and Maryland became less attractive as land grew scarcer. Many preferred to migrate to Pennsylvania or the Carolinas, where opportunities seemed greater. To replenish its labor force, planters in the Chesapeake region increasingly turned to enslaved Africans. In 1680, just seven percent of the population of Virginia and Maryland consisted of slaves; twenty years later, the figure was 22 percent. Most of these slaves did not come directly from Africa, but from Barbados and other Caribbean colonies or from the Dutch colony of New Netherlands, which the English had conquered in 1664 and renamed New York.

The status of blacks in seventeenth-century Virginia was extremely complex. Some were permanently unfree; others, like indentured servants, were allowed to own property and marry and were freed after a term of service. Some were even allowed to testify against whites in court and purchase white servants. In at least one county, black slaves who could prove that they had been baptized successfully sued for their freedom. There was even a surprising degree of tolerance of sexual intermixture and marriages across racial lines.

As early as the late 1630s, however, English colonists began to distinguish between the status of white servants and black slaves. In 1639, Maryland became the first colony to specifically state that baptism as a Christian did not make a slave a free person.

During the 1660s and 1670s, Maryland and Virginia adopted laws specifically designed to denigrate blacks. These laws banned interracial marriages and sexual relations and deprived blacks of property. Other laws prohibited blacks from bearing arms or traveling without written permission. In 1669, Virginia became the first colony to declare that it was not a crime to kill an unruly slave in the ordinary course of punishment. That same year, Virginia also prohibited masters from freeing slaves unless the freedmen were deported from the colony. Virginia also voted to banish any white man or woman who married a black, mulatto, or Indian.

The imposition of a more rigid system of racial slavery was accompanied by improved status for white servants. Unlike slaves, white servants and free workers could not be stripped naked and whipped. As the historian Edmund S. Morgan has suggested, a hardening of racial lines contributed to a growth in a commitment to democracy, liberty, and equality among white men.

In 1676, friction between backcountry farmers, landless former indentured servants, and coastal planters in Virginia exploded in violence in an incident known as Bacon’s Rebellion. Convinced that Virginia’s colonial government had failed adequately to protect them against Indians, backcountry rebels, led by Nathaniel Bacon, a wealthy landowner, burned the capital at Jamestown, plundered their enemy’s plantations, and offered freedom to any indentured servants who joined them. In the midst of the revolt, Bacon died of dysentery. Without his leadership, the uprising collapsed, but fear of servant unrest encouraged planters to replace white indentured servants with black slaves, set apart by a distinctive skin color. In 1660, there were fewer than a thousand slaves in Virginia and Maryland. But during the 1680s, their number tripled, rising from about 4,500 to 12,000.

Slavery for blacks made democracy for whites possible. Virginia erected a free white society on a foundation of black slavery. The freedom celebrated by Virginia’s Revolutionary generation was made possible by slavery. The degradation and exploitation of enslaved Africans made a commitment to freedom and equality among whites possible.

The Labor Problem during the Seventeenth Century

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, social elites in England were seeking ways to make laborers work harder. One solution was to exploit the labor of England’s “surplus” population. These people were put to work in Virginia as indentured servants. But there was a problem. These servants were constantly on the brink of revolt, and their numbers were diminishing. How else might England’s colonies meet their labor needs?

Another solution was slavery. In every tropical and semi-tropical region, Europeans would turn to slaves as a labor force. With slavery, there were no limits to the work that a master could command. In addition, masters could work enslaved women in the fields, something that they rarely did with white servants. But slaves had no incentive to work hard. The only way to get a slave to work was the threat of physical punishment, such as a whipping or even worse. In 1669, Virginia voted that the colony would pay a master the value of any slave that he killed in the course of discipline.

There was a third solution. What if the colonists themselves had an ethic of hard work, discipline, and frugality? What if they believed that the only way to achieve God’s blessing was to work hard? This mindset is known as the Protestant work ethic, and it rested on a particular religious faith that was indebted to the ideas of a religious reformer named John Calvin.

The people who brought this ethic to the English colonies were the New England Puritans.

Thinking Comparatively

Contrasting Forms of English Colonization

English colonization took a wide variety of forms, differing in motivation, demography, and labor systems.

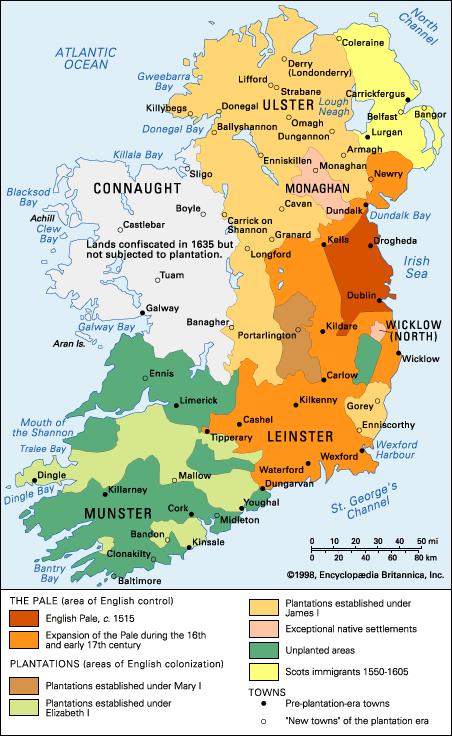

England’s first efforts at colonization took place not in the New World, but closer to home, in Ireland. Indeed, England’s efforts to conquer Ireland were continuing even when it was beginning to settle Virginia, Maryland, and New England.

The English treated the Irish cruelly, not as people to be pacified and put to work, but a people to be displaced. Conquest meant removal: dislodging the Irish population and replacing it with English and Scottish settlers. This policy became known as plantation settlement.

Physical separation was supposedly necessary between the colonists and the native population. Like the Roman Conquest, on which English colonization was modeled, conquest meant supplanting the indigenous population.

After an Irish rebellion in 1641, 11 million acres of northern Ireland were cleared of the native Irish population, 30,000 Irish were sold into slavery, and 100,000 English and Scots were planted in the area.

Such a harsh model of colonization did not bode well for future relations between the English and the indigenous North American peoples.

The settlement of North America was one of only many English efforts at New World colonization in the early 1600s. Besides settling Ireland, Virginia, and New England, England founded colonies in the Caribbean, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, and even the mainland coast of South America. At the same time, England established its first trading posts in India.

During the seventeenth century, when England established its first permanent colonies in North America, a crucial difference arose between the southern-most colonies, whose economy was devoted to production of staple crops, like tobacco or sugarcane, and the more diverse economies of the middle colonies and New England.

In the middle colonies and New England, the economy was organized around small family farms and urban communities engaged in fishing, handicrafts, and Atlantic commerce, with most of the population living in small compact towns.

In Maryland and Virginia, in contrast, the economy was structured around larger and much more isolated farms and plantations raising tobacco. In the Carolinas, economic life was organized around larger but less isolated plantations growing rice, indigo, coffee, cotton and sugar.

Motives for settlement also varied. Virginia was the product of a profit-seeking company known as a “joint-stock company.” Unlike a modern corporation, this company was not interested in long-term growth. Rather, its investors expected a rapid return on their investment. Also, these investors were personally liable, without limit, for any debts the company might incur. As a result, the Virginia Company was looking for a quick profit.

Religious persecution was a particularly powerful force motivating English colonization in a number of other colonies. Some 30,000 English Puritans immigrated to New England, while Maryland became a refuge for Roman Catholics, and Pennsylvania, southern New Jersey, and Rhode Island, havens for Quakers. Refugees from religious persecution included Baptists, Congregationalists, and Presbyterians, to say nothing of religious minorities from continental Europe, including Huguenots and members of the Dutch and German Reformed churches.