The Birth of the Women’s Rights Movement

The Birth of the Women’s Rights Movement

The women’s rights movement was a major legacy of radical reform. At the outset of the century, women could not vote or hold office in any state, they had no access to higher education, and they were excluded from professional occupations. American law accepted the principle that a wife had no legal identity apart from her husband. She could not be sued, nor could she bring a legal suit. She could not make a contract, nor could she own property. She was not permitted to control her own wages or gain custody of her children in case of separation or divorce. Under many circumstances, she was even deemed incapable of committing crimes.

Broad social and economic changes, such as the development of a market economy and a decline in the birthrate, opened employment opportunities for women. Instead of bearing children at two-year intervals after marriage, as was the general case throughout the colonial era, during the early nineteenth century, women bore fewer children and ceased childbearing at younger ages. During these decades, the first women’s college was established, and some men’s colleges first opened their doors to women students. More women postponed marriage or did not marrying at all. Unmarried women gained new employment opportunities as “mill girls” and elementary school teachers. A growing number of women achieved prominence as novelists, editors, teachers, and leaders of church and philanthropic societies.

Due in large measure to the women’s rights movement, American women made a number of significant gains in the decades before the Civil War. Instead of having to obtain a divorce from a state legislature, judges were given the power to grant divorces in most states. At the same time, the grounds for divorce were broadened in many states to include abuse or habitual drunkenness or other offenses. Following a divorce, mothers, in many states, received custody of young children unless they were proven to be unfit. Many states also granted women a number of fundamental legal rights. These included legal control over their own property and earnings; the right to sue in court; the right to make a will; and the right to inherit in their own name.

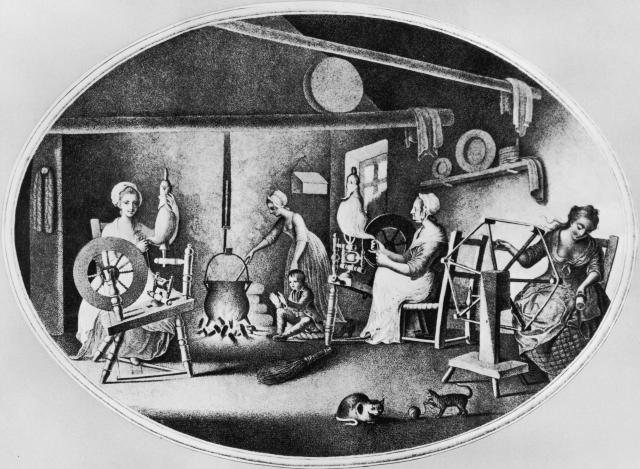

Although there were many improvements in the status of women during the first half of the century, women still lacked political and economic status when compared with men. As the franchise was extended to more white males, including large numbers of recent immigrants, the gap in political power between women and men widened. Even though women made up a core of supporters for many reform movements, men excluded them from positions of decision making and relegated them to separate female auxiliaries. Additionally, women lost economic status as production shifted away from the household to the factory and workshop. During the late eighteenth century, the need for a cash income led women and older children to engage in a variety of household industries, such as weaving and spinning. Increasingly, in the nineteenth century, these tasks were performed in factories and mills, where the workforce was largely male.

The fact that changes in the economy tended to confine women to a sphere separate from men had important implications for reform. Since women were believed to be uncontaminated by the competitive struggle for wealth and power, many argued that they had a duty—and the capacity—to exert an uplifting moral influence on American society.

Catharine Beecher (1800–1878) and Sarah J. Hale (1788–1879) helped lead the effort to expand women’s roles through moral influence. Beecher, the eldest sister of Harriet Beecher Stowe, was one of the nation’s most prominent educators before the Civil War. A woman of many talents and strong leadership ability, she wrote a highly regarded book on domestic science and spearheaded the campaign to convince school boards that women were suited to serve as schoolteachers. Hale edited the nation’s most popular women’s magazines, The Ladies Magazine and Godey’s Ladies Book. She led the successful campaign to make Thanksgiving a national holiday (during Lincoln’s administration), and she also composed the famous nursery rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb.”

Both Beecher and Hale worked tirelessly for women’s education (Hale helped found Vassar College). They gave voice to the grievances of women—the abysmally low wages paid to women in the needle trades (12.5 cents a day), the physical hardships endured by female operatives in the nation’s shops and mills (where women worked 14 hours a day), and the minimizing of women’s intellectual aspirations. Even though neither woman supported full equal rights for women, they were important transitional figures in the emergence of feminism. Each significantly broadened society’s definition of “women’s sphere” and assigned women vital social responsibilities: to shape their children’s character, to uplift their husbands morality, and to promote causes of “practical benevolence.”

Other women broke down old barriers and forged new opportunities in a more dramatic fashion. Frances Wright (1795–1852), a Scottish-born reformer and lecturer, received the nickname “The Great Red Harlot of Infidelity” because of her radical ideas about birth control, liberalized divorce laws, and legal rights for married women. In 1849 ,Elizabeth Blackwell (1821–1910) became the first American woman to receive a degree in medicine. A number of women became active as revivalists. Perhaps the most notable was Phoebe Palmer (1807–1874), a Methodist preacher who ignited religious fervor among thousands of Americans and Canadians.

History Through…

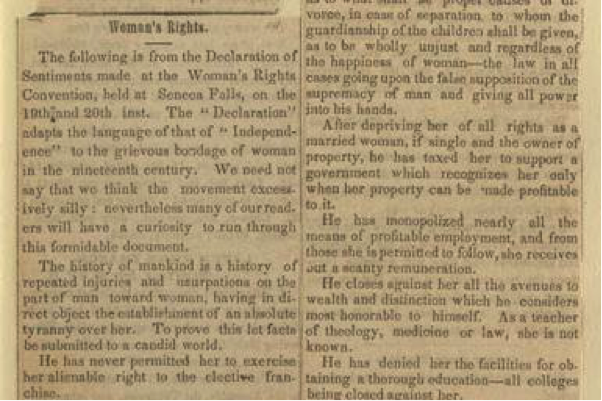

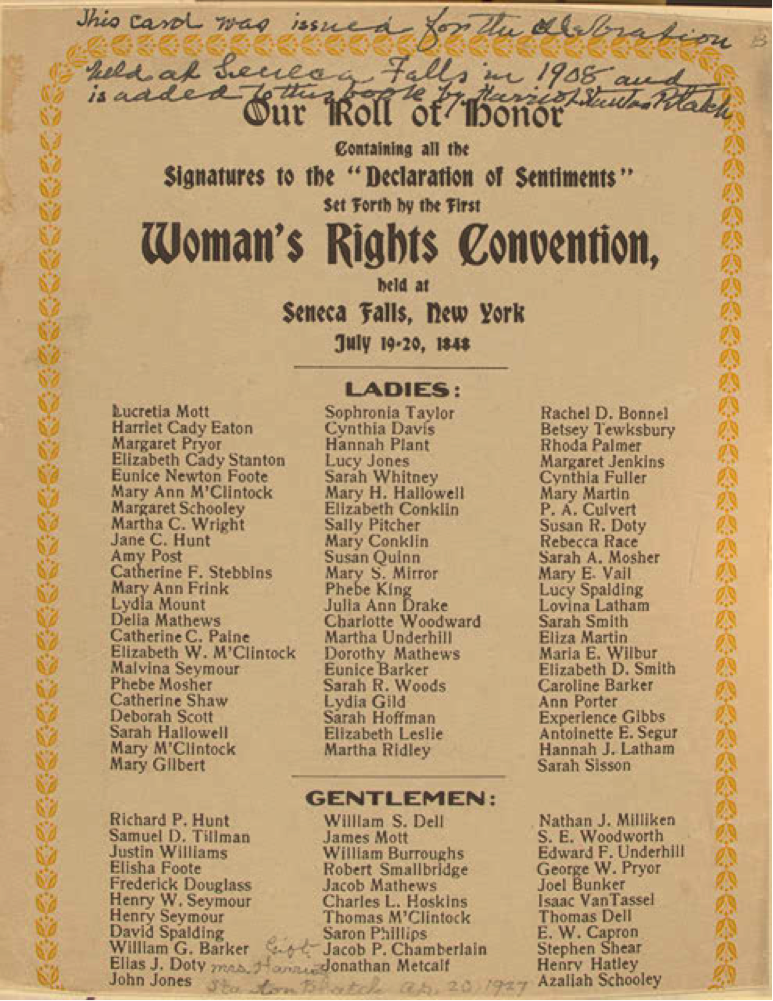

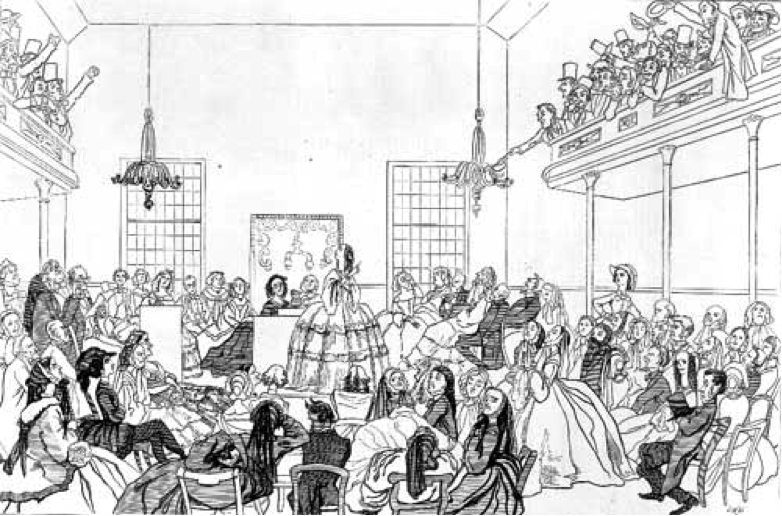

…Primary Sources: Women’s Rights: Seneca Falls Declaration and Resolutions (1848)

Seneca Falls Declaration and Resolutions, 1848, in Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Matilda Joslyn Gage, eds., History of Woman Suffrage (Rochester, 1889), 1: 75–80.

We hold these truth to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal…

The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her. To prove this, let facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has never permitted her to exercise her inalienable right to the elective franchise.

He has compelled her to submit to laws, in the formation of which she had no voice.

He has withheld from her rights which are given to the most ignorant and degraded men—both natives and foreigners.

Having deprived her of this first right of a citizen, the elective franchise, thereby leaving her without representation in the halls of legislation, he has opposed her on all sides.

He has made her, if married, in the eye of the law, civilly dead.

He has taken from her all rights in property, even to the wages she earns.

He has made her, morally, an irresponsible being, as she can commit many crimes with impunity, provided they be done in the presence of her husband. In the covenant of marriage, she is compelled to promise obedience to her husband, he becoming, to all intents and purposes, her master—the law giving him power to deprive her of her liberty, and to administer chastisement.

He has so framed the laws of divorce, as to what shall be the proper causes, and in case of separation, to whom the guardianship of children shall be given, as to be wholly regardless of the happiness of women—the law, in all cases, going into a false supposition of the supremacy of man, and giving all power into his hands.

After depriving her of all rights as a married woman, if single, and the owner of property, he has taxed her to support a government which recognizes her only when her property can be made profitable to it.

He has monopolized nearly all the profitable employments, and from those she is permitted to follow, she receives but a scanty remuneration. He closes against her all avenues to wealth and distinction which he considers most honorable to himself. As a teacher of theology, medicine, or law, she is not known. . . .

He has endeavored, in every way that he could, to destroy her confidence in her own powers, to lessen her self-respect, and to make her willing to lead a dependent and abject life.