Divisions within the Anti-Slavery Movement

Division Within the Antislavery Movement

Questions over strategy and tactics deeply divided the antislavery movement. At the 1840 annual meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society in New York, abolitionists split over questions such as women’s right to participate in the administration of the organization and the advisability of nominating abolitionists as independent political candidates. Garrison won control of the organization, and his opponents promptly walked out. From this point on, no single organization could speak for abolitionism.

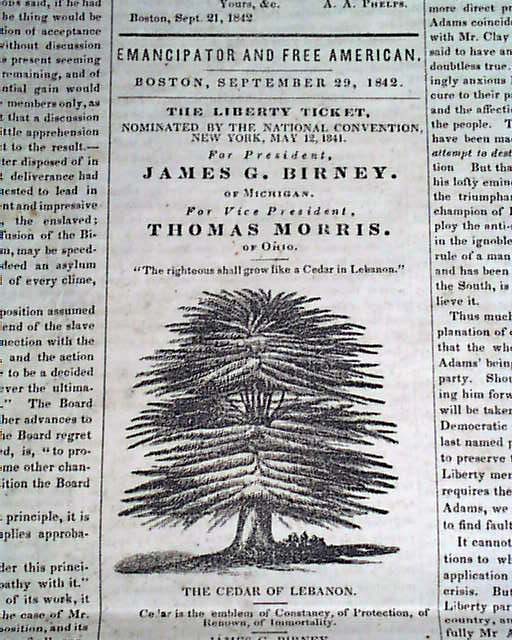

One group of abolitionists looked to politics as the answer to ending slavery and founded political parties for that purpose. The Liberty Party, founded in 1839 under the leadership of Arthur and Lewis Tappan, wealthy New York City businessmen, and James G. Birney, a former slaveholder, called on Congress to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia, to end the interstate slave trade, and to cease admitting new slave states to the Union. The party also sought the repeal of local and state “black laws” in the North, which discriminated against free blacks, much as segregation laws would in the post-Reconstruction South.

The Liberty Party nominated Birney for president in 1840 and again in 1844. Although it gathered fewer than 7,100 votes in its first campaign, it polled some 62,000 votes four years later and captured enough votes in Michigan and New York to deny Henry Clay the presidency.

In 1848, antislavery Democrats and Whigs merged with the Liberty Party to form the Free Soil Party. Unlike the Liberty Party, which was dedicated to the abolition of slavery and equal rights for African Americans, the Free Soil Party narrowed its demands to the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia and the exclusion of slavery from the federal territories. The Free Soilers also wanted a homestead law to provide free land for western settlers, high tariffs to protect American industry, and federally sponsored internal improvements. Campaigning under the slogan “free soil, free speech, free labor, and free men,” the new party polled 300,000 votes (or 10 percent) in the presidential election of 1848 and helped elect Whig candidate Zachary Taylor.

Other abolitionists, led by Garrison, took a more radical direction, advocating civil disobedience and linking abolitionism to other reforms such as women’s rights, world government, and international peace. Garrison and his supporters established the New England Non-Resistance Society in 1838. Members refused to vote, to hold public office, or to bring suits in court. In 1854, Garrison attracted notoriety by publicly burning a copy of the Constitution, which he called “a covenant with death and an agreement with Hell” because it acknowledged the legality of slavery.

African Americans played a vital role in the abolitionist movement, staging protests against segregated churches, schools, and public transportation. In New York and Pennsylvania, free blacks launched petition drives for equal voting rights. Northern blacks also had a pivotal role in the “underground railroad,” which provided escape routes for Southern slaves through the Northern states and into Canada. African-American churches offered sanctuary to runaways, and black “vigilance” groups in cities such as New York and Detroit battled slave catchers who sought to recapture fugitive slaves.

Fugitive slaves, such as William Wells Brown, Henry Bibb, and Harriet Tubman, advanced abolitionism by publicizing the horrors of slavery. Their firsthand tales of whippings and separation from spouses and children combated the notion that slaves were contented under slavery and undermined belief in racial inferiority. Tubman risked her life by making nineteen trips into slave territory to free as many as 300 slaves. Slaveholders posted a reward of $40,000 for the capture of the “Black Moses.”

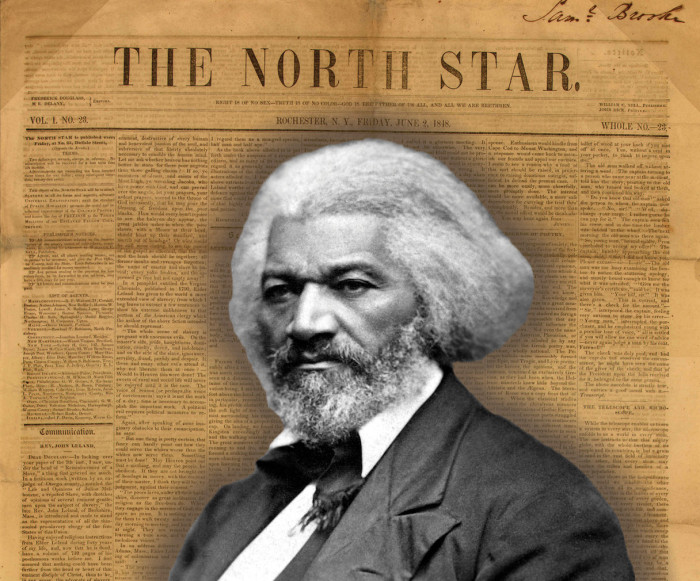

Frederick Douglass was the most famous fugitive slave and black abolitionist. The son of a Maryland slave woman and an unknown white father, Douglass was separated from his mother and sent to work on a plantation when he was six years old. At the age of twenty, in 1838, he escaped to the North using the papers of a free black sailor. In the North, Douglass became the first runaway slave to speak out against slavery. When many Northerners refused to believe that this eloquent orator could possibly have been a slave, he responded by writing an autobiography that identified his previous owners by name. Although he initially allied himself with William Lloyd Garrison, Douglass later started his own newspaper, The North Star, and supported political action against slavery.

During the 1850s, many blacks had become pessimistic about defeating slavery. Some African Americans looked again to colonization as a solution. In the fifteen months following passage of the federal Fugitive Slave Law in 1850, which required the return of runaway slaves and put even free blacks at risk, 13,000 free blacks fled the North for Canada. In 1854, Martin Delany (1812–1885), a Pittsburgh doctor who had studied medicine at Harvard, organized the National Emigration Convention to investigate possible sites for black colonization in Haiti, Central America, and West Africa.

Other blacks began to argue in favor of violence. Black abolitionists in Ohio adopted resolutions encouraging slaves to escape and called on their fellow citizens to violate any law that “conflicts with reason, liberty and justice, North or South.” A meeting of fugitive slaves in Cazenovia, New York, declared that “the State motto of Virginia, ‘Death to Tyrants,’ is as well the black man’s as the white man’s motto.” By the late 1850s, a growing number of free blacks had concluded that it was just as legitimate to use violence to secure the freedom of the slaves as it had been to establish the independence of the American colonies.

Over the long run, the fragmentation of the antislavery movement worked to the advantage of the cause. Henceforth, Northerners could support whichever form of antislavery best reflected their views. Moderates could vote for political candidates with abolitionist sentiments without being accused of radical Garrisonian views or of advocating violence for redress of grievances.

Catalyst for Women’s Rights

A public debate over the proper role of women in the antislavery movement, especially their right to lecture to audiences composed of both sexes, led to the first organized movement for women’s rights. By the mid-1830s, more than a hundred female antislavery societies had been created and women abolitionists were circulating petitions, editing abolitionist tracts, and organizing antislavery conventions.

A key question was whether women abolitionists would be permitted to lecture to “mixed” audiences of men and women. In 1837 a national women’s antislavery convention resolved that women should overcome this taboo: “The time has come for women to move in that sphere which providence has assigned her, and no longer remain satisfied with the circumscribed limits which corrupt custom and a perverted application of Scripture have encircled her.”

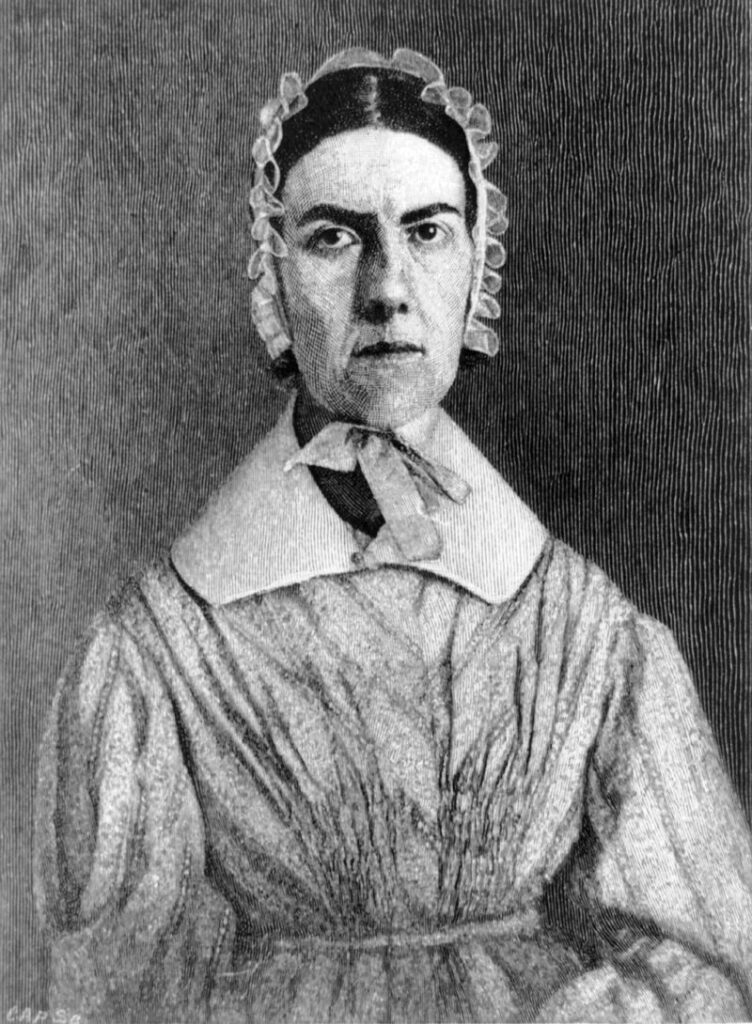

Angelina Grimké (1805–1879) and her sister Sarah (1792–1873)—two sisters from a wealthy Charleston, South Carolina, slaveholding family—were the first women to break the restrictions and widen women’s sphere through their writings and lectures before mixed audiences. In 1837, Angelina gained national notoriety by lecturing against slavery to audiences that included men as well as women. Shocked by this breach of the separate sexual spheres ordained by God, ministers in Massachusetts called on their fellow clergy to forbid women the right to speak from church pulpits.

Sarah Grimké in 1840 responded with a pamphlet entitled, “Letters on the Condition of Women and the Equality of the Sexes,” one of the first modern statements of feminist principles. She denounced the injustice of lower pay and denial of equal educational opportunities for women. Her pamphlet expressed outrage that women were “regarded by men, as pretty toys or as mere instruments of pleasure” and were taught to believe that marriage is “the sine qua non [indispensable element] of human happiness and human existence.” Men and women, she concluded, should not be treated differently, since both were endowed with innate natural rights.

In 1840, after the American Anti-Slavery Society split over the issue of women’s rights, the organization named three female delegates to a World Anti-Slavery Convention to be held in London later that year. There, these women were denied the right to participate in the convention on the grounds that their participation would offend British public opinion. The convention relegated them to seats in a balcony.

Eight years later, Lucretia Mott (1793–1880), who earlier had been denied the right to serve as a delegate to the World Anti-Slavery Convention, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815–1902) organized the first women’s rights convention in history. Held in July 1848 at Seneca Falls, New York, the convention drew up a Declaration of Sentiments, modeled on the Declaration of Independence, which opened with the phrase “All men and women are created equal.” It named fifteen specific inequities suffered by women, and after detailing “a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of men toward woman,” the document concluded that “he has endeavored, in every way that he could, to destroy her confidence in her own powers, to lessen her self-respect, and to make her willing to lead a dependent and abject life.”

Among the resolutions adopted by the convention, only one was not ratified unanimously—that women be granted the right to vote. Of the 66 women and 34 men who signed the Declaration of Sentiments at the convention including black abolitionist Frederick Douglass, only two lived to see the ratification of the women’s suffrage amendment to the constitution 72 years later.

By mid-century, women’s rights conventions had been held in every Northern state. Despite ridicule from the public press—The Worcester (Massachusetts) Telegraph denounced women’s rights advocates as “Amazons”—female reformers contributed to important, if limited, advances against discrimination. They succeeded in gaining adoption of Married Women’s Property Laws in a number of states, granting married women control over their own income and property. Several states gave women preference for custody over young children following a divorce or separation. Several states gave women the right to sue and be sued, and adopted permissive divorce laws that allowed women to exit abusive and loveless marriages. A Connecticut law, for example, granted divorce for any “misconduct” that “permanently destroys the happiness of the petitioner and defeats the purposes of the marriage relationship.”

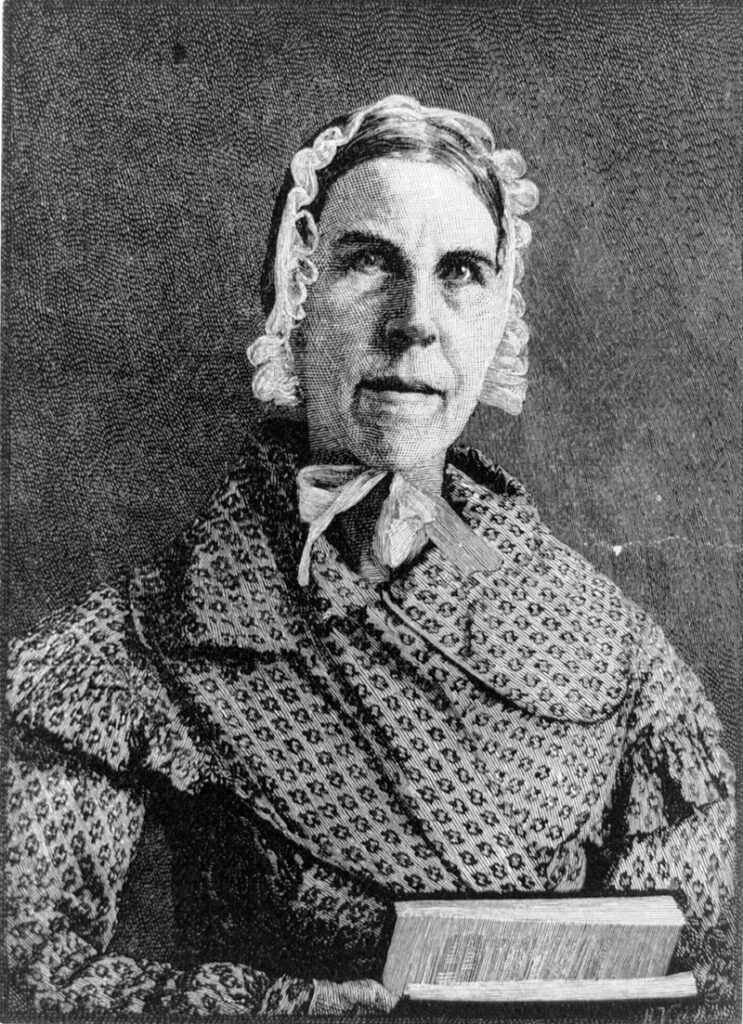

Black women were active in the campaign to extend equal rights to women. Sojourner Truth, who had been born into slavery in New York State’s Hudson River Valley around 1797, gained fame as a preacher, singer, and orator for abolition and women’s rights. At a women’s rights convention in Akron, Ohio, in 1851, she is reported to have demanded that Americans recognize the African American women’s right to equality. “I could work as much and eat as much as a man—when I could get it—and bear de lash as well!” she told the crowd. “And a’n’t I a woman?”