Radical Reform

Radical Reform

The initial thrust of reform—moral reform—was to rescue the nation from infidelity and intemperance. A second line of reform, social reform, attempted to alleviate sources of human misery, such as crime, cruelty, disease, and ignorance. A third line of reform, radical reform, sought national regeneration by eliminating not only slavery but also racial and sexual discrimination.

Early Antislavery Efforts

As late as the 1750s, no churches discouraged their members from owning or trading in slaves. Slaves could be found in each of the thirteen American colonies. Before the American Revolution, only the colony of Georgia had temporarily sought to prohibit slavery because its founders did not want a workforce that would compete with the convicts they planned to transport from England.

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, however, protests against slavery had become widespread. By 1804, nine states north of Maryland and Delaware had either emancipated their slaves or adopted gradual emancipation plans. Both the United States and Britain in 1808 outlawed the African slave trade.

The emancipation of slaves in the Northern states and the prohibition of the African slave trade generated optimism that slavery was dying. Congress in 1787 had barred slavery from the Old Northwest, the region north of the Ohio River to the Mississippi River. The number of slaves freed by their masters rose dramatically in the upper South during the 1780s and 1790s, and more antislavery societies had been formed in the South than in the North. At the present rate of progress, predicted one religious leader in 1791, within 50 years it will “be as shameful for a man to hold a Negro slave, as to be guilty of common robbery or theft.”

By the early 1830s, however, the development of the Cotton Kingdom proved that slavery was not on the road to extinction. Despite the end of the African slave trade, the slave population continued to grow, climbing from 1.5 million in 1820 to more than 2 million a decade later.

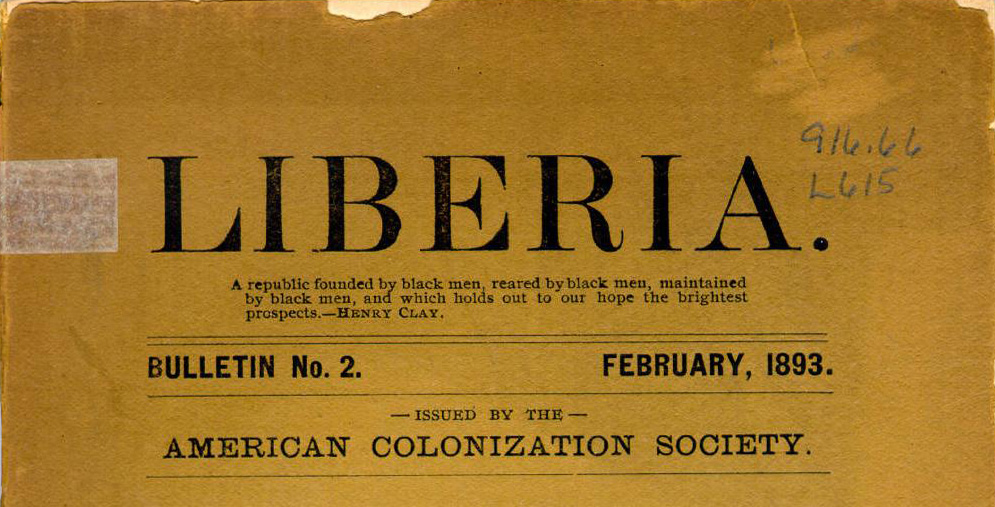

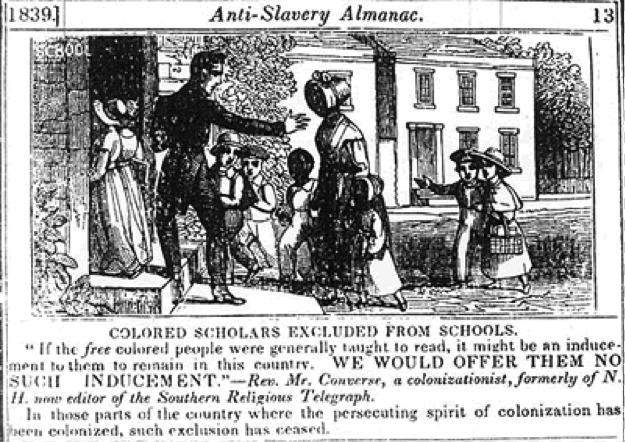

A widespread belief that blacks and whites could not co-exist and that racial separation was necessary encouraged futile efforts at deportation and overseas colonization. In 1817, a group of prominent ministers and politicians formed the American Colonization Society to resettle free blacks in West Africa, to encourage planters voluntarily to emancipate their slaves, and to create a group of black missionaries who would spread Christianity in Africa. During the 1820s, Congress helped fund the cost of transporting free blacks to Africa.

A few blacks supported African colonization in the belief that it provided the only alternative to continued degradation and discrimination. Paul Cuffe (1759–1817), a Quaker sea captain who was the son of a former slave and an Indian woman, led the first experiment in colonization. In 1815, he transported 38 free blacks to the British colony of Sierra Leone, on the western coast of Africa, and devoted thousands of his own dollars to the cause of colonization. In 1822, the American Colonization Society established the colony of Liberia, in west Africa, for resettlement of free American blacks.

It soon became apparent that colonization was a wholly impractical solution to the nation’s slavery problem. Each year the nation’s slave population rose by roughly 50,000, but in 1830 the American Colonization Society succeeded in persuading only 259 free blacks to migrate to Liberia, bringing the total number of blacks colonized in Africa to a mere 1,400.

The Rise of Abolitionist Sentiment in the North

Initially, free blacks led the movement condemning colonization and Northern discrimination against African Americans. As early as 1817, more than 3,000 members of Philadelphia’s black community staged a protest against colonization, at which they denounced the policy as “little more merciful than death.”

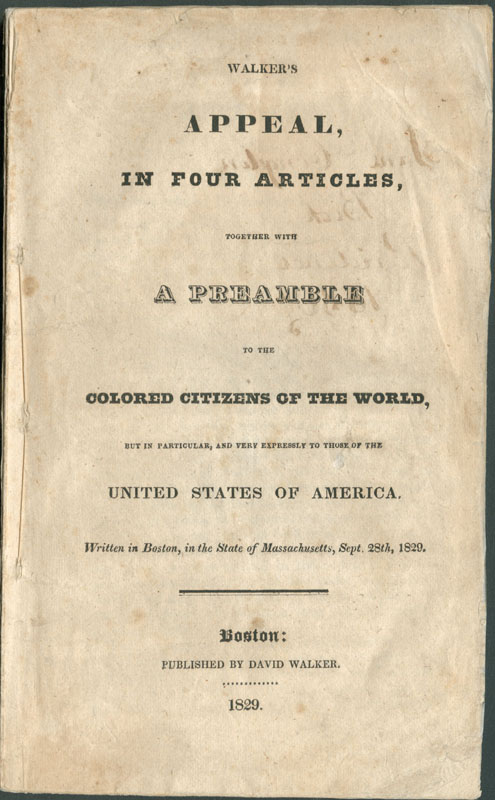

In 1829, David Walker (1785–1830), the free black owner of a second-hand clothing store in Boston, issued the militant Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World. The Appeal threatened insurrection and violence if calls for the abolition of slavery and improved conditions for free blacks were ignored. The next year, forty black delegates from eight states held the first of a series of annual conventions denouncing slavery and calling for an end to discriminatory laws in the northern states.

The idea of abolition received impetus from William Lloyd Garrison (1805–1879). In 1829 the 25-year-old white Bostonian added his voice to the outcry against colonization, denouncing it as a cruel hoax designed to promote the racial purity of the Northern population while doing nothing to end slavery in the South. Instead, he called for “immediate emancipation.” By immediate emancipation, he meant the immediate and unconditional release of slaves from bondage without compensation to slaveowners.

In 1831, Garrison founded The Liberator, a militant abolitionist newspaper that was the country’s first publication to demand an immediate end to slavery. On the front page of the first issue, he defiantly declared: “I will not equivocate—I will not excuse—I will not retreat a single inch—AND I WILL BE HEARD.” Incensed by Garrison’s proclamation, the state of Georgia offered a $5,000 reward to anyone who brought him to the state for trial.

Within four years, 200 antislavery societies had appeared in the North. In a massive propaganda campaign to proclaim the sinfulness of slavery, they distributed a million pieces of abolitionist literature and sent 20,000 tracts directly to the South.

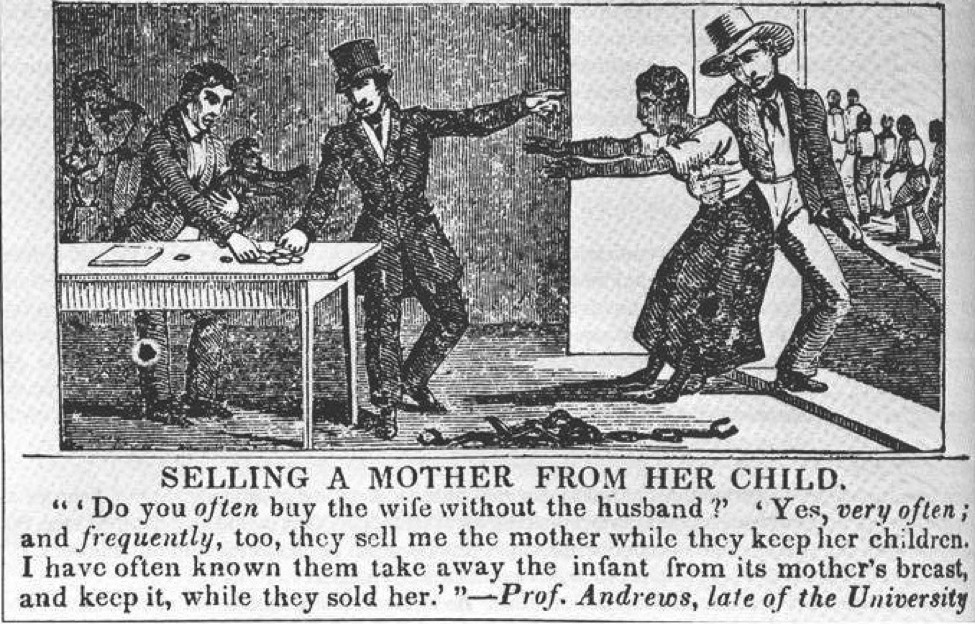

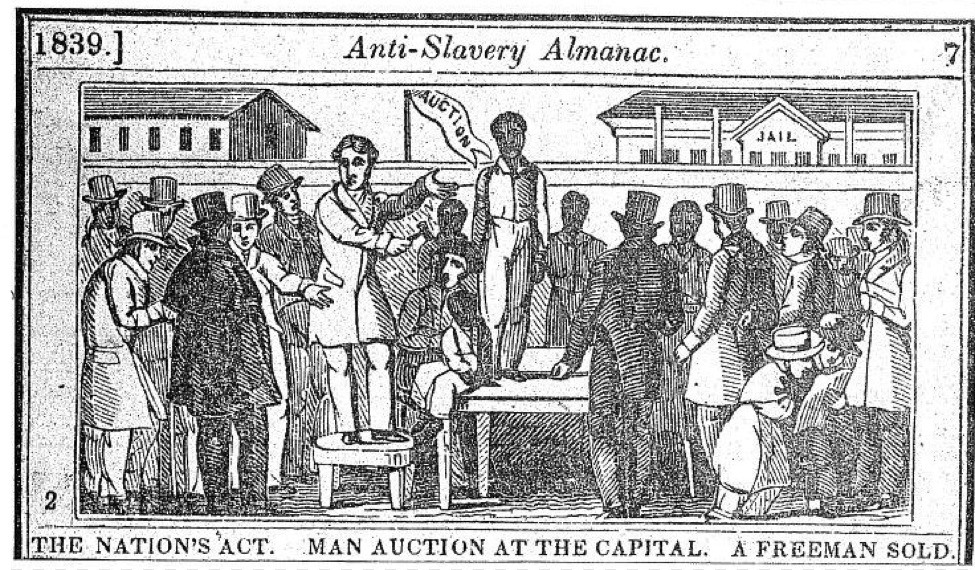

Abolitionist Arguments and Public Reaction

Abolitionists attacked slavery on several grounds. Slavery was illegal because it violated the principles of natural rights to life and liberty embodied in the Declaration of Independence. Justice, said Garrison, required that the nation “secure to the colored population…all the rights and privileges that belong to them as men and as Americans.” Slavery was sinful because slaveholders, in the words of abolitionist Theodore Weld, had usurped “the prerogative of God.” Masters reduced a “God-like being” to a manipulable “THING.” Slavery also encouraged sexual immorality and undermined the institutions of marriage and the family. Abolitionists not only charged that slave masters sexually abused and exploited slave women, but also, in some older Southern states such as Virginia and Maryland, they bred slaves for sale to the more recently settled parts of the Deep South.

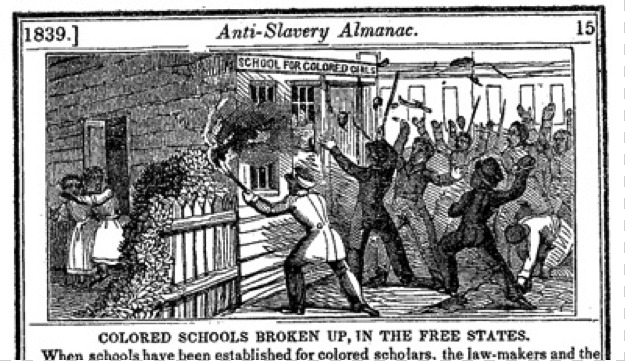

Slavery was economically retrogressive, abolitionists argued, because slaves, motivated only by fear, did not exert themselves willingly. By depriving their labor force of any incentive for performing careful and diligent work and by barring slaves from acquiring and developing productive skills, planters hindered improvements in crop and soil management. Abolitionists also charged that slavery impeded the development of towns, canals, railroads, and schools.

Antislavery agitation provoked a harsh public reaction in both the North and the South. The U.S. Postmaster General refused to deliver antislavery tracts to the South. In each session of Congress between 1836 and 1844, the House of Representatives adopted gag rules allowing that body to table resolutions or petitions concerning the abolition of slavery automatically.

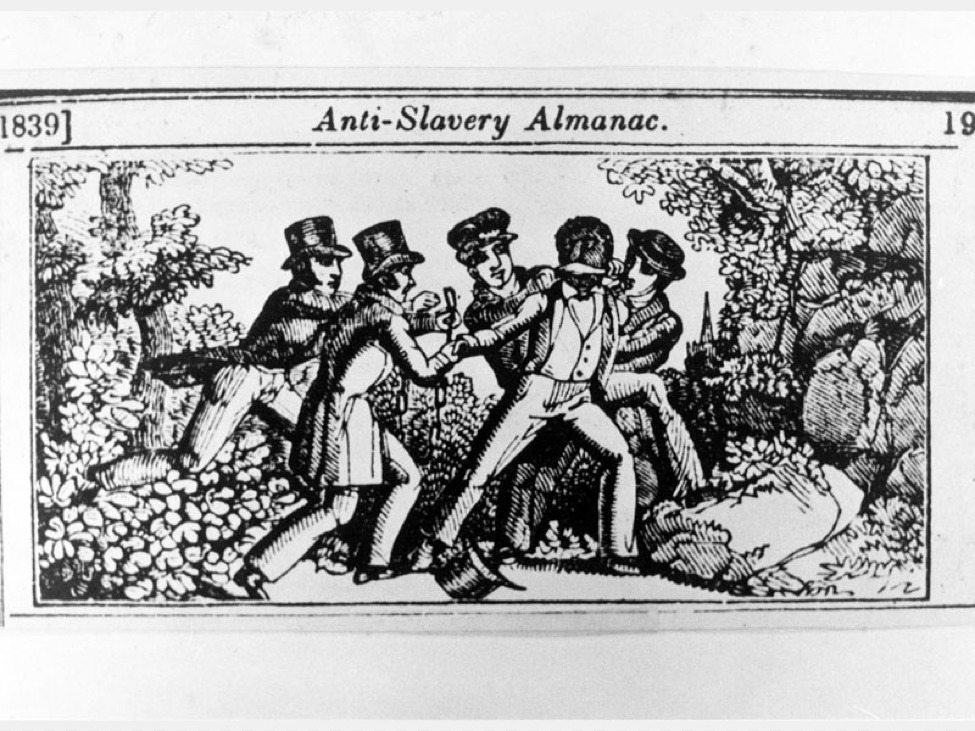

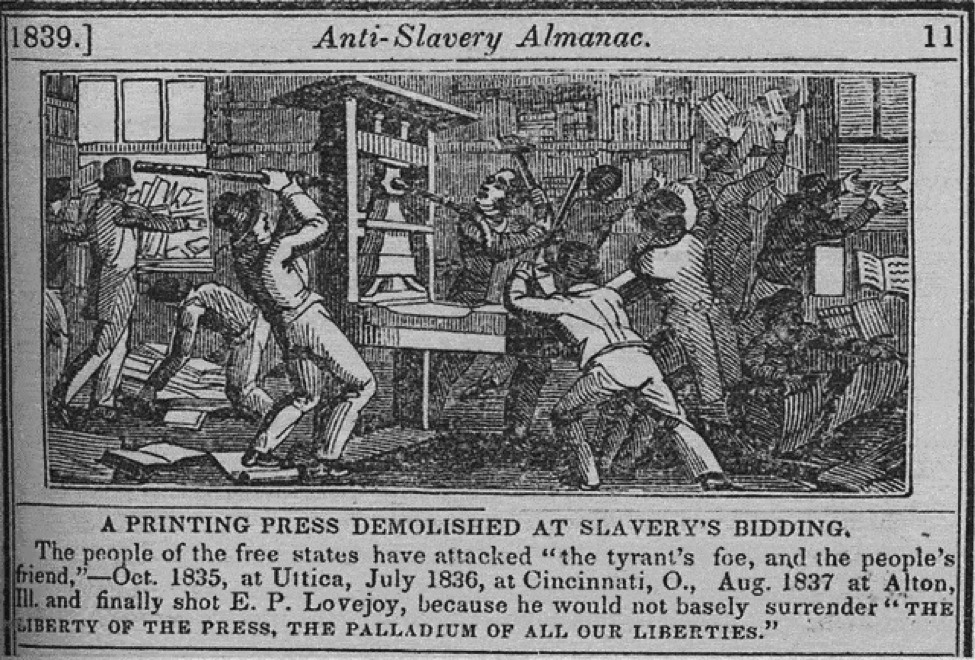

Mobs led by “gentlemen of property and standing” attacked the homes and businesses of abolitionist merchants, destroyed abolitionist printing presses, disrupted antislavery meetings, and terrorized black neighborhoods. Crowds pelted abolitionist reformers with eggs and even stones. During anti-abolitionist rioting in Philadelphia in October 1834, a white mob destroyed 45 homes in the city’s black community. A year later, a Boston mob dragged Garrison through the streets and almost lynched him before authorities removed him to a city jail for his own safety.

In 1837, the abolitionist movement acquired its first martyr when an antiabolitionist mob in Alton, Illinois, murdered Reverend Elijah Lovejoy, editor of a militant abolitionist newspaper. Three times mobs destroyed Lovejoy’s printing presses and attacked his house. When a fourth press arrived, Lovejoy armed himself and guarded the new press at the warehouse. The anti-abolitionist mob set fire to the warehouse, shot Lovejoy as he fled the building, and dragged his mutilated body through the town.

History Through…

…Primary Sources: Abolitionist Literature

Review the following images.

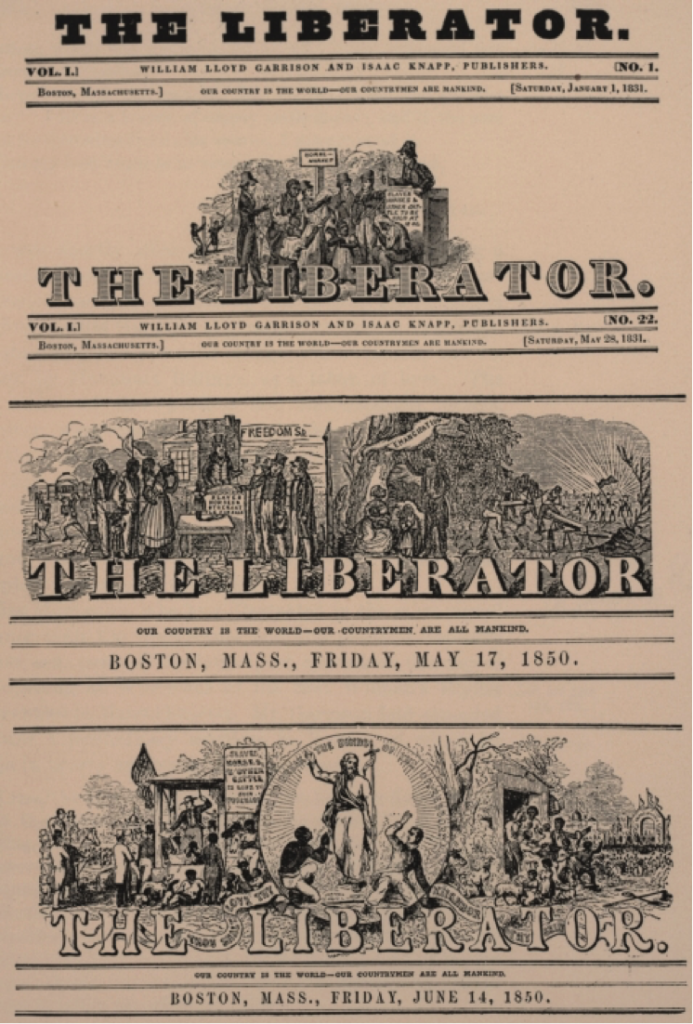

The Liberator

From the 1830s through the Civil War, William Lloyd Garrison’s antislavery newspaper The Liberator was the leading antislavery newspaper. Over the period of its publication, it had three mastheads.

Look closely at the mastheads.