Social Reform

Social Reform

The nation’s first reformers tried to improve the nation’s moral and spiritual values by distributing Bibles and religious tracts, promoting observance of the Sabbath, and curbing drinking. Beginning in the 1820s a new phase of reform—social reform—spread across the country, directed at crime, illiteracy, poverty, and disease. Reformers sought to solve these social problems by creating new institutions to deal with them—including prisons, public schools, and asylums for the deaf, the blind, and the mentally ill.

The Struggle for Public Schools

Of all the ideas advanced by antebellum reformers, none was more original than the principle that all American children should be educated to their full capacity at public expense. Reformers viewed education as the key to individual opportunity and the creation of an enlightened and responsible citizenry. Reformers also believed that public schooling could be an effective weapon in the fight against juvenile crime and an essential ingredient in the assimilation of immigrants.

From the early days of settlement, Americans attached special importance to education. During the seventeenth century, the New England Puritans required every town to establish a public school supported by fees from all but the very poorest families (a requirement later repealed). In the late eighteenth century, Thomas Jefferson popularized the idea that a democratic republic required an enlightened and educated citizenry. Early nineteenth-century educational reformers extended these ideas and struggled to make universal public education a reality. As a result of their efforts, the Northern states were among the first jurisdictions in the world to establish tax-supported, tuition-free public schools.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the United States had the world’s highest literacy rate—approximately seventy-five percent. Apprenticeship was a major form of education, supplemented by church schools, charity schools for the poor, and private academies for the affluent. Many youngsters learned to read in informal dame schools, in which a woman would take girls and boys into her own home. Formal schooling was largely limited to those who could afford to pay. Many schools admitted pupils regardless of age, mixing young children with young adults in their twenties. A single classroom could contain as many as eighty pupils.

The campaign for public schools began in earnest in the 1820s, when religiously motivated reformers advocated public education as an answer to poverty, crime, and deepening social divisions. At first, many reformers championed Sunday schools as a way “to reclaim the vicious, to instruct the ignorant, to secure the observance of the Sabbath…and to raise the standard of morals among the lower classes of society.” But soon, reformers began to call for public schools.

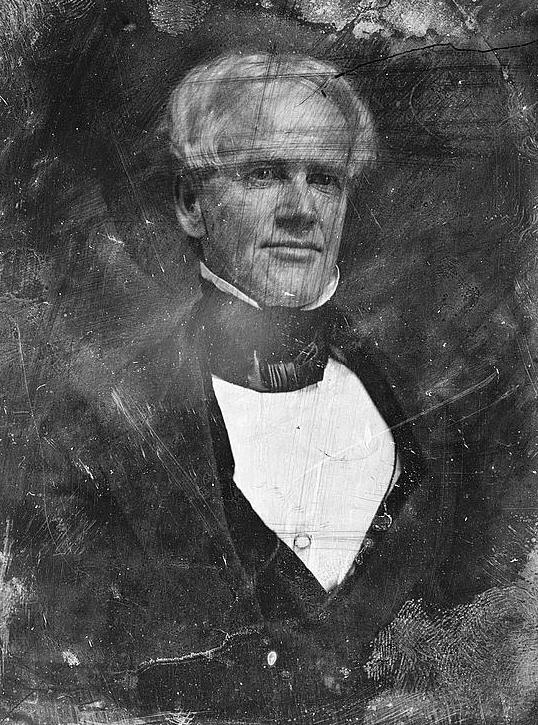

Horace Mann (1796–1859) of Massachusetts, the nation’s leading educational reformer, led the fight for government support for public schools. As a state legislator, in 1837 Mann took the lead in establishing a state board of education and his efforts resulted in a doubling of state expenditures on education. He also won state support for teacher training, an improved curriculum in schools, the grading of pupils by age and ability, and a lengthened school year. He was partially successful in curtailing the use of corporal punishment. In 1852, three years after Mann left office to take a seat in the U.S. Congress, Massachusetts adopted the first compulsory school attendance law in American history.

Educational opportunities, however, were not available to all. Most Northern cities specifically excluded African Americans from the public schools. Finally, in 1855, Massachusetts became the first state to admit students to public schools without regard to “race, color, or religious opinions.”

In 1832, Prudence Crandall, a Quaker schoolteacher in Canterbury, Connecticut, sparked a major controversy by admitting Sarah Harris, the daughter of a free black farmer, into her school. After white parents withdrew their children from the school, the young schoolteacher tried to turn her school into an institution for the education of free blacks. Hostile neighbors broke the school’s windows, contaminated its well with manure, and denied its students seats on stagecoaches and in pews in church. In 1833, after the state adopted a law making it a crime to teach black students who were not residents of Connecticut, state authorities arrested Crandall. She was tried twice, convicted, and jailed. After her release, a local mob attacked Crandall’s school building with crowbars and attempted to burn the structure. It never opened again.

Women and religious minorities also experienced discrimination. For women, education beyond the level of handicrafts and basic reading and writing was largely confined to separate female academies and seminaries for the affluent. Emma Hart Willard opened one of the first academies offering an advanced education to women in Philadelphia in 1814. Many public school teachers showed an anti-Catholic bias by using texts that portrayed the Catholic Church as a threat to republican values and reading passages from a Protestant version of the Bible.

Beginning in New York City in 1840, Catholics decided to establish their own system of schools in which children would receive a religious education as well as training in the arts and sciences.

In higher education, a few institutions opened their doors to African Americans and women. In 1833 Oberlin College, where Charles G. Finney taught, became the nation’s first co-educational college. Four years later, Mary Lyon established the first women’s college, Mount Holyoke, to train teachers and missionaries. A number of western state universities also admitted women. In addition, three colleges for African Americans were founded before the Civil War, and a few other colleges, including Oberlin, Harvard, Bowdoin, and Dartmouth, admitted small numbers of black students.

The reform impulse brought other changes in higher education. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, most colleges offered their students, who usually enrolled between the ages of twelve and fifteen, only a narrow training in the classics designed to prepare them for the ministry. During the 1820s and 1830s, in an effort to adjust to the “spirits and wants of the age,” colleges broadened their curricula to include the study of history, literature, geography, modern languages, and the sciences. The entrance age was also raised and the requirements demanded of students were broadened.

The number of colleges also increased. Most of the new colleges, particularly in the South and West, were church-affiliated, but several states established state universities. Before the Civil War, 16 states provided some financial support to higher education, and by the 1850s, New York City offered tuition-free education from elementary school to college.

Sight and Sound

The Problem of Crime in a Free Society

Before the American Revolution, punishment for crimes generally involved some form of corporal punishment, ranging from the death penalty for serious crimes to public whipping, confinement in stocks, and branding for lesser offenses. Jails were used as temporary confinement for criminal defendants awaiting trial or punishment. Conditions in these early jails were abominable. Cramped cells held large groups of offenders of both sexes and all ages. Debtors were confined with hardened criminals. Prisoners customarily had to pay the expenses of food and lodging.

During the pre–Civil War decades, reformers began to view crime as a social problem—a product of environment and parental neglect—rather than the result of original sin or innate human depravity. Reformers believed it was the duty of a humane society to remove the underlying causes of crime, to sympathize and to show patience toward criminals and to try to reform them, instead of whipping or confining them in stocks.

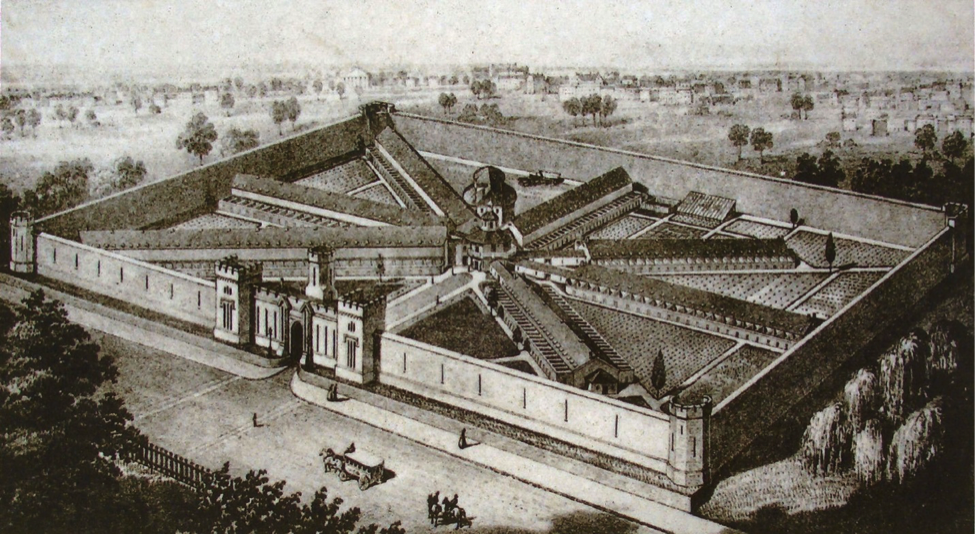

Revulsion over the spectacle of public punishment led to the rapid construction of penal institutions in which the “disease” of crime could be quarantined and inmates could be gradually rehabilitated in a carefully controlled environment. Two rival prison systems competed for public support. After constructing Auburn Prison, New York State authorities adopted a system in which inmates worked in large workshops during the day and slept in separate cells at night. Convicts had to march in lockstep and refrain from speaking or even looking at each other. In Pennsylvania’s Eastern State Penitentiary, constructed in 1829, authorities placed even greater stress on the physical isolation of prisoners. Every prison cell had its own exercise yard, work space, and toilet facilities. Under the Pennsylvania plan, prisoners lived and worked in complete isolation from each other. Called “penitentiaries” or “reformatories,” these new prisons reflected the belief that hard physical labor and solitary confinement might encourage introspection and instill habits of discipline that would rehabilitate criminals.

The legal principle that a criminal act should be legally punished only if the offender was fully capable of distinguishing between right and wrong opened the way to one of the most controversial aspects of American jurisprudence—the insanity defense. The question arose dramatically in 1835 when a deranged Englishman named Richard Lawrence walked up to President Andrew Jackson and fired two pistols at him from a distance of six feet. Incredibly, both guns misfired, and Jackson was unhurt. Lawrence believed that Jackson’s attack on the second Bank of the United States had prevented him from obtaining money that would have enabled him to claim the English throne. The court, ruling that Lawrence was clearly suffering from a mental delusion, found him insane, and not subject to criminal prosecution. Instead, he was confined to an asylum for treatment of his mental condition.

Another major effort in social reform was the drive to outlaw capital punishment. Before the 1830s, most states reduced the number of crimes punishable by death and began to perform executions out of public view, lest the public be stimulated to acts of violence by the spectacle of hangings. In 1847, Michigan became the first modern jurisdiction to outlaw the death penalty. Rhode Island and Wisconsin soon followed.

Imprisonment for debt also came under attack. As late as 1816, an average of 600 residents of New York City were in prison at any one time for failure to pay debts. More than half owed less than $50. New York’s debtor prisons provided no food, furniture, or fuel for their inmates, who would have starved without the assistance of relatives and the charity of humane societies. In a Vermont case, state courts imprisoned a man for a debt of fifty-four cents, and in Boston, a woman was taken from her three children as a result of a $3 debt.

Increasingly, reformers regarded imprisonment for debt as irrational, since imprisoned debtors were unable to work and pay off their debts. Piecemeal reform led to the abolition of debtor prisons, as states eliminated the practice of jailing people for trifling debts, and then forbade the jailing of women and veterans.

Asylums for Society’s Outcasts

A number of reformers devoted their attention to the problems of the mentally ill, the deaf, and the blind. In 1841, Dorothea Dix (1802–1887), a 39-year-old former schoolteacher, volunteered to give religious instruction to women incarcerated in the East Cambridge, Massachusetts, House of Correction. Inside the House of Correction, she was horrified to find mentally ill inmates dressed in rags and confined to a single dreary, unheated room. Shocked by what she saw, she embarked on a lifelong crusade to reform the treatment of the mentally ill.

After a two-year secret investigation of every jail and almshouse in Massachusetts, Dix issued a report to the state legislature. The mentally ill, she found, were mixed indiscriminately with paupers and hardened criminals. Many were confined “in cages, closets, cellars, stalls, pens! Chained, naked, beaten with rods and lashed into obedience.” Dix then carried her campaign for state-supported asylums nationwide, persuading more than a dozen state legislatures to improve institutional care for the insane.

Through the efforts of reformers such as Thomas Gallaudet and Samuel Gridley Howe, institutions to care for the deaf and blind began to appear.

In 1817, Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet (1787–1851) established the nation’s first school in Hartford, Connecticut, to teach deaf-mutes to read and write, read lips, and communicate through hand signals. Samuel Gridley Howe (1801–1876), the husband of Julia Ward Howe, composer of the “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” accomplished for the blind what Gallaudet achieved for the deaf. He founded the country’s first school for the blind in Boston and produced printed materials with raised type.