Roots of the Reform Impulse

Sources of the Reform Impulse

What factors gave rise to the reform impulse and why was it unleashed with such vigor in pre–Civil War America? Reformers had many different reasons for wanting to change American society. Some hoped to remedy the distresses created by social disorder, violence, and widening class divisions. Others found motivation in a religious vision of a godly society on earth.

Social Problems on the Rise

During the early nineteenth century, poverty, lawlessness, violence, and vice appeared to be increasing at an alarming rate. In New York, the nation’s largest city, crime rose far faster than in the overall population. Between 1814 and 1834, the city’s population doubled, but reports of crime quadrupled. Gangs, bearing such names as Plug Uglies and Bowery B’hoys, prowled the streets, stealing from warehouses and private residences. Public drunkenness was a common sight. By 1835, there were nearly 3,000 drinking places in New York—one for every fifty persons over the age of fifteen.

Prostitution also generated concern. By 1850, a reported 6,000 “fallen women” strolled the city streets. Mob violence evoked particular fear. In a single decade, 1834–1844, 200 incidents of mob violence occurred in New York. Adding to the sense of alarm were scenes of heart-wrenching poverty, such as children standing barefoot outside hotels selling matches.

Social problems were not confined to large cities like New York. During the decades before the Civil War, newspapers reported hundreds of incidences of duels, lynchings, and mob violence. In the slave states and southwestern territories, men frequently resolved quarrels by dueling. In one 1818 duel between two cousins, the combatants faced off with shotguns at four paces. Lynchings too were widely reported. In 1835, the citizens of Vicksburg, Mississippi, attempted to rid the city of gambling and prostitution by raiding gaming houses and brothels and lynching five gamblers. In urban areas, mob violence increased in frequency and destructiveness. Between 1810 and 1819 there were seven major riots; in the 1830s there were 115.

A nation in which the Vice President had to carry a gun while presiding over the Senate—lest senators attack each other with knives or pistols—seemed to confirm criticism by Europeans that democracy inevitably led to anarchy. Incidents of crime and violence led many Americans to ask how a free society could maintain stability and moral order. Americans sought to answer this question through religion, education, and social reform.

A New Moral Sensibility

More than anxiety over lawlessness, violence, and vice sparked the reform impulse during the first decades of the nineteenth century. America’s revolutionary heritage, the philosophy of the Enlightenment, and religious zeal all contributed to a sensitivity to human suffering and a boundless faith in humankind’s capacity to improve social institutions.

Many pre–Civil War reformers saw their efforts as an attempt to realize the ideals enshrined in the Declaration of Independence. Invoking the principles of liberty and equality set forth in the Declaration, abolitionists, such as William Lloyd Garrison, attacked slavery. Feminists, such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton, called for equal rights for women.

The philosophy of the Enlightenment, with its belief in the people’s innate goodness and with its rejection of the inevitability of poverty and ignorance, was another important source of the reform impulse. Those who espoused the Enlightenment philosophy argued that the creation of a more favorable moral and physical environment could alleviate social problems.

Religion further strengthened the reform impulse. Almost all the leading reformers were devoutly religious men and women who wanted to deepen the nation’s commitment to Christian principles. Two trends in religious thought—religious liberalism and evangelical revivalism—strengthened reformers’ zeal. Religious liberalism was an emerging form of humanitarianism that rejected the harsh Calvinist doctrines of original sin and predestination. Its preachers stressed the basic goodness of human nature and each individual’s capacity to follow the example of Christ.

William Ellery Channing (1780–1842) was America’s leading exponent of religious liberalism. His beliefs, proclaimed in a sermon he delivered in Baltimore in 1819, became the basis for American Unitarianism. The new religious denomination stressed individual freedom of belief, a united world under a single God, and the mortal nature of Jesus Christ, whom individuals should strive to emulate. Channing’s beliefs stimulated many reformers to work toward improving the conditions of the physically handicapped, the criminal, the impoverished, and the enslaved.

The Second Great Awakening

Enthusiastic religious revivals swept the nation in the early-nineteenth century, providing further religious motivation for the reform impulse. On August 6, 1801, some 25,000 men, women, and children gathered in the small frontier community of Cane Ridge, Kentucky, in search of religious salvation. Twenty-five thousand was a fantastically large number of people at a time when the population of the whole state of Kentucky was a quarter million, and the state’s largest city, Lexington, had only 1,795 residents. The Cane Ridge camp meeting went on for a week. Baptists, Methodists, and ministers of other denominations joined together to preach to the vast throng. Within three years, similar revivals occurred throughout Kentucky, Tennessee, and Ohio. This great wave of religious fervor became known as the Second Great Awakening.

The revivals inspired a widespread sense that the nation was standing close to the millennium, a thousand years of peace and benevolence when sin, war, and tyranny would vanish from the earth. Evangelical leaders urged their followers to reject selfishness and materialism and repent their sins. To the revivalists, sin was no metaphysical abstraction. Luxury, high living, indifference to religion, preoccupation with worldly and commercial matters—all were denounced as sinful. If men and women did not seek God through Christ, the nation would face divine retribution. Evangelical revivals helped instill in Americans a belief that they had been chosen by God to lead the world toward “a millennium of republicanism.”

Charles Grandison Finney (1792–1875), the “father of modern revivalism,” led revivals throughout the Northeast. Finney became the North’s leading revivalist. Despite his lack of formal theological training, he was remarkably successful in converting souls to Christ. Finney’s message was that anyone could experience a redemptive change of heart and a resurgence of religious feeling. He prayed for sinners by name; he held meetings that lasted night after night for a week or more; he set up an “anxious bench” at the front of the meeting, where the almost-saved could receive special prayers. He also encouraged women to participate actively in revivals. If only enough people converted to Christ, Finney told his listeners, the millennium—Christ’s reign on earth—would arrive within three years.

Revival meetings attracted both frontier settlers and city folk, slaves and masters, farmers and shopkeepers. The revivals had their greatest appeal among isolated farming families on the Western and Southern frontier and among upwardly mobile merchants, shopkeepers, artisans, skilled laborers in the expanding commercial and industrial towns of the North. They also drew support from social conservatives who feared that America would disintegrate into a state of anarchy without the influence of evangelical religion. Above all, revivals attracted large numbers of young women, who took an active role organizing meetings, establishing church societies, and editing religious publications.

Religious Diversity

The early nineteenth century was a period of extraordinary religious ferment. Church membership climbed steeply, until three-quarters of all Americans were affiliated with a church. The religious landscape grew increasingly diverse. A number of older denominations—notably the Baptists, Catholics, and Methodists—expanded rapidly while a host of new denominations and movements arose, including the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the Disciples of Christ, the Mormons, and the Unitarian and Universalist Churches.

During the late eighteenth century, church membership was low and falling. Deism—a movement that emphasized reason rather than revelation and denied that a divine creator interfered with the workings of the universe—and skepticism seemed to be spreading. A French immigrant claimed that “religious indifference is imperceptibly disseminated from one end of the continent to the other.” Yet by 1830, foreign observers considered the United States the most religious country in the western world.

Religious revivals played a critical role in this outpouring of religion. In part, revivalism represented a response to the growing separation of church and state that followed the American Revolution. When states deprived established churches of state support (as did Virginia in 1785, Connecticut in 1818, and Massachusetts in 1833), Protestant ministers held revivals to ensure that America would remain a God-fearing nation. The popularity of revivals also reflected the hunger of many Americans for an emotional religion that downplayed creeds and rituals and instead emphasized conversion.

No religious group grew more rapidly during the pre–Civil War era or faced more bitter hostility than the Roman Catholic Church. From just 25,000 members and six priests in 1776, the Catholic Church in America grew to three million members in 1860. With English, French, German, Irish, and Mexican members, it was not only the nation’s largest denomination, it was also America’s first multicultural church. Concerned that many immigrants were only nominally Catholic, the Church established urban missions and launched religious revivals to strengthen Catholics’ religious identity. Somewhat similar to the Protestant Evangelical revivals, the Catholic revivals featured rousing sermons and encouraged piety, fervor, and devotion. By establishing its own schools and system of hospitals, orphanages, and benevolent societies, the Church sought to help Catholics preserve their faith in the face of Protestant proselytizing.

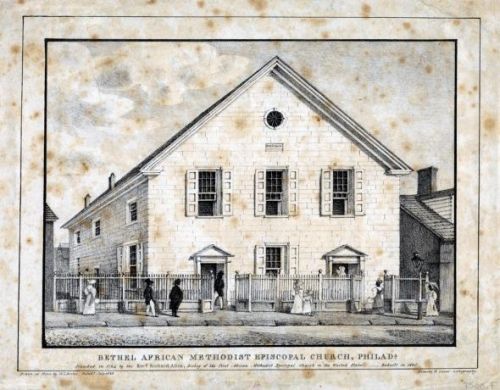

Prejudice and discrimination led African Americans to create their own churches. The first were established in Philadelphia, after the city’s black Methodists were ordered to sit in a segregated gallery. Between 1804 and 1815, African Americans formed their own Baptist, Methodist, and Presbyterian Churches in eastern cities. In 1816, the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the first autonomous black denomination, was founded.

Another religious group that grew sharply before the Civil War was American Jewry. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, there were only about 2,000 Jews in the United States, six Jewish congregations, no Jewish newspapers, and not a single rabbi. By 1860, when the number of American Jews had climbed to 150,000, Jewish newspapers reached readers in 1,250 communities, and Jews had served in the legislatures of Georgia, Indiana, New York, North Carolina, and South Carolina. Jews faced less discrimination and hostility than Catholics, in part because the Jewish community was scattered and in part because most Jews shed the distinctive dress, long sideburns, and other customs that set European Jews apart. Yet, although they adapted to American life in many ways, Jews vigorously resisted threats to their identity, strongly opposing state laws that limited public office to Christians, bans against commerce on the Christian Sabbath, and the recitation of Christian prayers in schools.

The founders of the discipline of sociology associated modernization with secularization, that is, with a falling away from religious belief. But in the United States, the modernization of society was associated with an outpouring of religious faith.