Utopian Communities

Forecasting the Future

Utopian Communities

Between the 1820s and 1840s, individuals who believed in the perfectibility of the social and political order founded hundreds of “utopian communities.” These experimental communal societies were called utopian communities because they provided blueprints for an ideal society.

The characteristics of these communities varied widely. One of the earliest perfectionist societies was popularly known as the Shakers. Founded in 1776 by “Mother” Ann Lee, an English immigrant, the Shakers believed that the millennium was at hand and that the time had come for people to renounce sin. Shaker communities regarded their male and female members as equals. Thus, both sexes served as elders and deacons. Aspiring to live like the early Christians, the Shakers adopted communal ownership of property and a way of life emphasizing simplicity. Dress was kept simple and uniform. Shaker architecture and furniture was devoid of ornament—no curtains on windows, carpets on floors, or pictures on walls—but they were pure and elegant in form.

The two most striking characteristics of the Shaker communities were their dances and abstinence from sexual relations. The Shakers believed that religious fervor should be expressed through the head, heart, and mind, and their ritual religious practices included shaking, shouting, and dancing. Viewing sexual intercourse as the basic cause of human sin, the Shakers adopted strict rules concerning celibacy. They attempted to replenish their membership by admitting volunteers and taking in orphans. Today, the Shakers have all but died out.

Another utopian effort was Robert Owen’s experimental community at New Harmony, Indiana, which reflected the influence of Enlightenment ideas. Owen, a paternalistic Scottish industrialist, was deeply troubled by the social consequences of the industrial revolution. Inspired by the idea that people are shaped by their environment, Owen purchased a site in Indiana where he sought to establish common ownership of property and abolish religion. At New Harmony, the marriage ceremony was reduced to a single sentence and children were raised outside of their natural parents’ home. The community lasted just three years, from 1825 to 1828.

Some 40 utopian communities based their organization on the ideas of the French theorist Charles Fourier, who hoped to eliminate poverty through the establishment of scientifically organized cooperative communities called “phalanxes.” Each phalanx was to be set up as a “joint-stock company,” in which profits were divided according to the amount of money members had invested, their skill, and their labor. In the phalanxes, women received equal job opportunities and equal pay, equal participation in decision-making, and the right to speak in public assemblies. Although one Fourier community lasted for eighteen years, most were unsuccessful.

The currents of radical antislavery thought inspired Frances Wright, a fervent Scottish abolitionist, to found Nashoba Colony in 1826, near Memphis, Tennessee, as an experiment in interracial living. She established a racially integrated cooperative community in which slaves were to receive an education and earn enough money to purchase their own freedom. Publicity about Fanny Wright’s desire to abolish the nuclear family, religion, private property, and slavery created a furor, and the community dissolved after only four years.

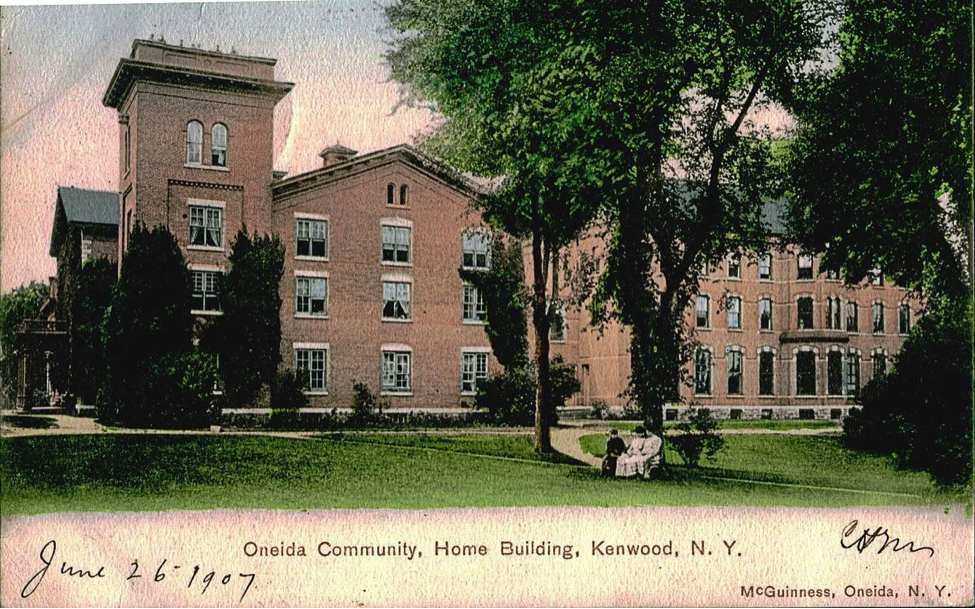

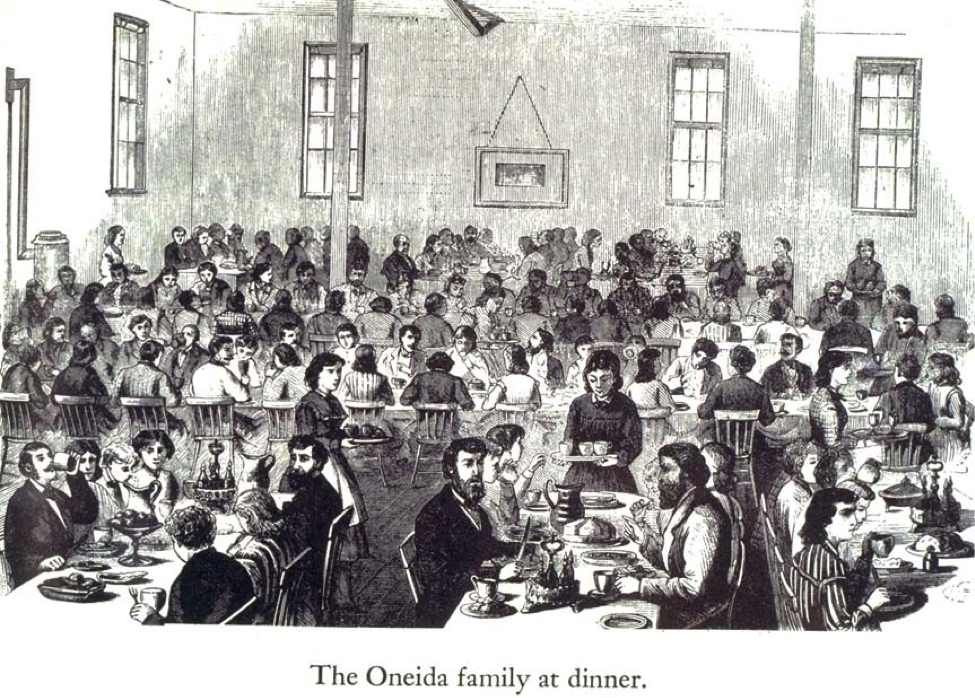

Perhaps the most successful—and notorious—experimental colony was John Humphrey Noyes’s Oneida Community. A lawyer who was converted in one of Charles Finney’s revivals, Noyes believed that the millennium would occur only when people strove to become perfect through an “immediate and total cessation from sin.”

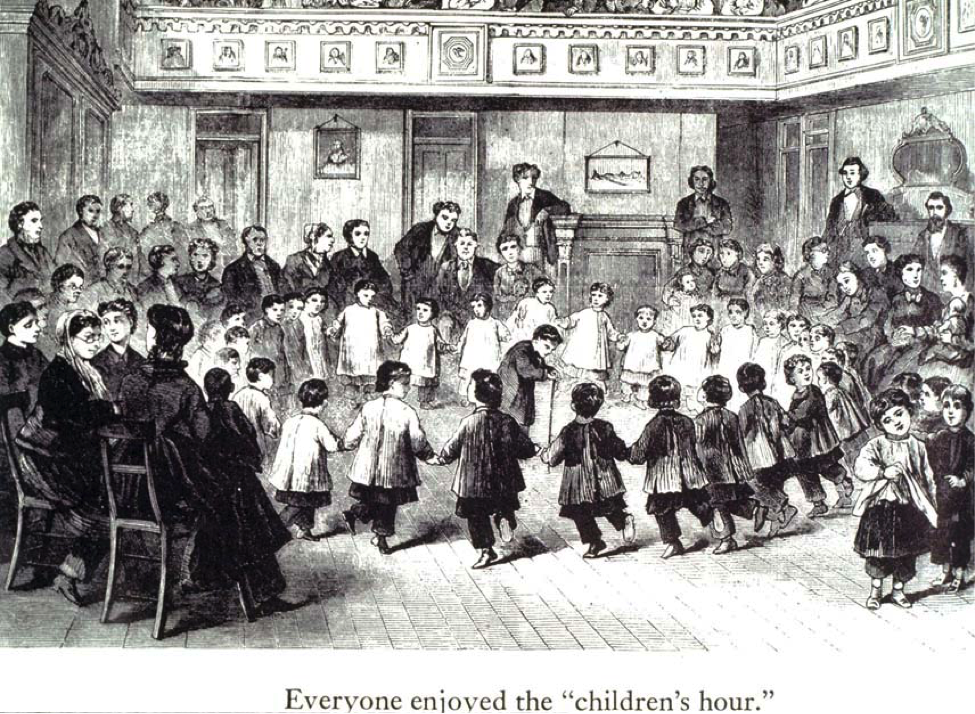

In Putney, Vermont, in 1835 and in Oneida, New York, in 1848, Noyes established perfectionist communities that practiced communal ownership of property and “complex marriage.” Complex marriage involved the marriage of each member of the community to every member of the opposite sex. Exclusive emotional or sexual attachments were forbidden, and sexual relations were arranged through an intermediary in order to protect a woman’s individuality and give her a choice in the matter. Men were required to practice coitus interruptus (withdrawal) as a method of birth control, unless the group had approved of the couple’s conceiving offspring. After the Civil War, the community conducted experiments in eugenics, the selective control of mating to improve the hereditary qualities of children. Other notable features of the community were mutual criticism sessions and communal childrearing. Noyes left the community in 1879 and fled to Canada to escape prosecution for adultery. As late as the early 1990s, descendants of the original community could be found working at the Oneida silverworks, which became a corporation after Noyes’s departure.

Common themes that link most of these utopian communities include a collective economy, efforts to improve the status and roles of women, a desire to extend the intimacy of the family to a much broader set of social relationships, and a belief in the perfectibility of human beings and human institutions.

Review the following images.

The Pre-Civil War Reform Ends

The Pre-Civil War reform era came to a symbolic end in 1865 when William Lloyd Garrison, the abolitionist, closed down his militant abolitionist newspaper The Liberator and called on the American Anti-Slavery Society to disband. Its mission, he announced, had been accomplished.

The first half of the nineteenth century witnessed the rise of the first secular movements in history to educate the deaf and the blind, care for the mentally ill, extend equal rights to women, and abolish slavery. Inspired by the revolutionary ideals of the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights, the Enlightenment faith in reason, and liberal and evangelical religious principles, educational reformers created a system of free public education, prison reformers constructed specialized institutions to reform criminals, temperance reformers sought to end the drinking of liquor, and utopian socialists established ideal communities to serve as models for a better world.

The Civil War brought this period of ferment and experimentation to a close. The war’s grim brutality undercut the spirit of hope and boundless possibilities that had pervaded pre–Civil War America. Nevertheless, the reformers of the early nineteenth century would stand as an example and an inspiration to future generations of Americans.