Myth Versus Reality

Historical Facts & Fiction

Salem Witchcraft

In January 1692, eleven-year-old Abigail Williams and nine-year-old Betty Parris, the daughter of a minister, began to behave peculiarly. They experienced uncontrollable spasms and twitches and barked like dogs. Abigail flapped her arms like a bird and said that a witch was trying to get her. Soon, other children acted in a similar fashion. Thus began one of the most dishonorable episodes in American history. By the time it was all over 19 men and women plus two dogs were executed for witchcraft.

The mass hysteria caused another 55 people to repent their sins while an additional 130 people awaited trial for witchcraft before the whole episode was over.

One of history’s primary functions is to dispel popular beliefs that are widely held but factually incorrect. Few subjects are more enveloped in myth than the Salem witch scare.

Some of the myths are obviously incorrect. No one in Salem was burned at the stake. Nor were witchcraft accusations leveled exclusively at women or at the elderly or the poor. Fourteen women and five men were hanged, and one man was “pressed” to death, with heavy stones, for refusing to plead guilty or innocent. Other myths deserve greater scrutiny.

Among the first to be accused of witchcraft was an Indian slave, probably from Guyana, named Tituba. Tituba believed the only way she could avoid hanging was to plead guilty to the charges. She spoke about an encounter with a thin white man who showed her a book with the names of nine Salem witches in it.

The scare only ended when the children accused the governor’s wife of witchcraft. A special grand jury was convened that quickly threw out more than a hundred charges of witchcraft.

Myth #1: By 1692, almost no educated people believed in witchcraft.

Even educated people believed that the Devil was present and active on Earth. Sir Isaac Newton was not only one of the creators of calculus and modern physics, but wrote extensively on the devil, witchcraft, and ghosts.

Myth #2: The Salem witchcraft scare was a one-of-a-kind incident, an anomaly in the history of New England.

Between 1645 and 1663, about eighty people throughout the Massachusetts Bay Colony were accused of practicing witchcraft, and thirteen women and two men were executed.

What made the Salem episode unique was not only the number of accusations and executions, but the fact that public authorities, who had imposed restraints on witchcraft accusations by requiring high levels of evidence, reduced the standards in 1692 by not requiring physical evidence against the accused. Instead, the authorities allowed the use of “spectral” evidence—the images that had appeared in witnesses’ dreams.

Myth #3: The scare was confined to a single town, Salem.

The witch trials took place in Salem Village, rather than in Salem proper. Salem Village was subsequently renamed Danvers.

Of the approximately 150 people formally charged during the crisis, only twenty-four resided in Salem Village. The witchcraft crisis in fact enveloped much of Essex County, the entire northeastern portion of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. More people had been accused of witchcraft in neighboring Andover than in Salem Town or Salem Village.

Myth #4: The scare was a product of hallucinations brought on by a disease or by poisoning.

Medical explanations are not consistent with the symptoms that the accusers had.

Instead, the witchcraft scare grew out of social tensions that had been mounting for decades. In Salem and in eastern Massachusetts more generally, there was increasing tension between those engaged in agriculture and those involved in the rapidly growing commercial and trading sectors of the economy. Disparities in wealth were growing, with those involved in commerce benefiting most, contributing to a deepening divide among the colonists.

The Salem witch scare also immediately followed a major conflict with Indians aligned with the French. Known as King Williams’s War, this conflict destroyed many settlements north of Massachusetts and led many settlers to retreat to Massachusetts Bay Colony.

A further source of strain was a political upheaval between 1686 and 1689, in which Massachusetts Bay Colony was stripped of its original charter and made into a royal colony. As a result, the colony was stripped of its independence in matters of politics and religion.

Myth #5: The scare was insignificant, and had no lasting impact.

This ugly episode helped to discredit belief in witchcraft. England ended executions for witchcraft in 1735. Massachusetts Bay Colony itself would apologize for the episode just a few years after it took place.

But it is important to remember that while this grizzly episode was over, other instances of mass hysteria would take place many times in the future.

Lessons of History

Lessons of History: Policy Brief on the History of Immigration

Policymakers often invoke the “lessons of history” when they make decisions. Often these analogies are crude or misleading and are twisted or embellished to justify decisions that have already been made. But when deployed intelligently and responsibly, history can be helpful in informing decisions.

Let’s use as an example immigration, a subject that has been intensively studied by historians. How might historical perspective inform the contemporary debate?

- As a proportion of the population, immigration today is actually smaller than it was at the turn of the twentieth century, when about 15 percent of the population consisted of immigrants. Today, the figure is 13 percent.

- The arguments against immigration have tended to remain fairly consistent over time: That immigrants threatened jobs of low wage workers and did not share the values of the dominant culture.

- In the past, much immigration was circular, with large numbers of immigrants eventually leaving the United States to return to their country of origin. A greater emphasis on border control has reduced circular migration.

- The United States has been highly successful in assimilating immigrants.

- Absorption and assimilation was largely complete by the second generation irrespective of the immigrants’ country of origin.

- Anti-immigration sentiment has been greatest during tough economic times.

- Hostility toward particular immigrant groups tends to subside over time.

- Immigrants are not as poor as some believe; they have high rates of savings and send money to relatives in their country of origin.

- U.S. immigration policy often has very little to do with trends and patterns of immigration. Immigration rates largely reflect economic conditions in the United States or the country of origin.

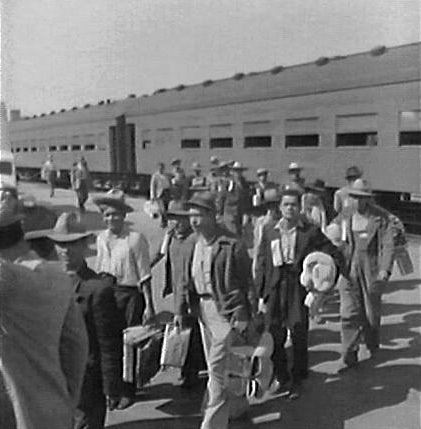

- Before 1965 there were no numerical limits on immigration from Latin America or the Caribbean. In that year, Congress placed a cap on the number of immigrants from any country (to 20,000, which was substantially less than the 50,000 a year that had come from Mexico in earlier years). Undocumented immigration increased because the number of permanent resident visas decreased and because a temporary labor program (the Bracero Program) ended.

- Heightened border controls had limited impact on the influx of Latin American immigrants, but had the ironic effect of curtailing the outflow of immigrants.

- “Family reunification” policies that exempted close relatives of citizens from immigration quotas have contributed to the increase in the number of immigrants from Latin America and Asia since 1965.

- From 1970 to 2010 the population born in Latin America increased more than 11 times, despite stepped up border enforcement and deportations.