History Through…Language

History Through…

…Names

The English colonists who first arrived in what is now the United States drew their names from a very small pool. About half of all boys in the late sixteenth-century “Lost Colony” of Roanoke Island were named John, Thomas or William, and more than half of newborn girls in the Massachusetts Bay Colony were named Mary, Elizabeth or Sarah. It was also common for New Englanders to give girls names that resonated with Puritan religious values, such as Charity and Patience.

Toward the end of the seventeenth century, greater diversity in names appeared as growing numbers of German, Scottish, and Scot-Irish immigrants arrived. German immigrants introduced such names as Frederick, Johann, Matthias, Barbara, and Veronica, while the Scot-Irish brought such names as James, Andrew, Alexander, Archibald and Patrick. Gaelic names including Duncan, Donald and Kenneth also appeared, while the Welsh contributed Hugh, Owen and David.

By the late eighteenth century, girls began to receive classical names such as Lucretia, Cynthia, and Lavina, and more parents gave their children middle names. Less formal names also appeared, including Nancy, Sally and Betsy. The final decades of the eighteenth century also witnessed the revival of old Anglo-Saxon names such as Alfred, Egbert, Harold, Edmund and Edith, Ethel and Audrey. This effort to evoke the distant past was an expression of a cultural movement known as Romanticism.

Naming practices offer a window into how values and tastes have shifted over time. The historical record offers a particularly rich source of insights into why certain names grow in popularity while others go out of style. It is striking that many of today’s most popular children’s names, especially girls’ names, were virtually unknown just half a century ago. Some popular names fell out of favor, like Lisa or Beth, while others, including Jayden, Justin, and Jason for boys, and Mia or Maya, Kayla, and Madison among girls, became much more common.

Certain long-term trends in naming patterns stand out. Fewer parents today name a first born child for a father or mother. Fathers’ influence on children’s names appears to have waned, with many fathers ceding the choice of a first name to the mother in exchange for using his last name. Today’s parents appear to spend more time musing over a child’s name than parents in the past. The most striking trend in recent years has been a heightened emphasis on individuality, originality, and adventurousness in names.

Names tied to a particular era—like Barbara, Nancy, Karen, or Susan—or ethnic groups—like Giuseppe and Helga—have declined in popularity, although Biblical and antique names (like Abigail, Hannah, Caleb, and Oliver) have grown in frequency as have names associated with defunct occupations (like Cooper, Carter, and Mason).

In the past, there were particularly marked regional differences in naming patterns, with antebellum white Southern males especially likely to use surnames or ancestral names as first names (such as Ambrose, Ashley, Braxton, Jubal, Kirby, or Porter), reflecting an emphasis on family honor. The parents of baby boomers were especially likely to give their children informal names (like Tom or Jeff or Judy) or diminutives (like Stevie or Tommy or Suzy), and to confine their names to a relatively small pool of conventional options, while their children often gave more formal, exotic, or idiosyncratic names (such as Jonathan instead of John or Elizabeth instead of Beth) to their offspring.

Semantic associations and sound preferences appear to have a strong impact on the names parents bestow on their children. In recent years, there has been a tendency to adopt names that begin with a hard “k” (as opposed to baby boomer names that often ended with a “k,” like Frank, Jack, Mark, or Rock), or end with “-er” or “-a”, while girls’ names that end with “-ly” (like Emily) have declined in frequency.

Place names, like Georgia, have grown more common, while girls’ names associated with flowers or decoration (like Violet), have declined as have names that seem old fashioned (like Gladys).

Names are signals that send out messages, and parents today seek to emphasize their child’s individuality and to give them names that will seem appropriate when they enter adulthood.

There is a tendency among the general public to assume that mass media have a particularly great impact on naming practices, but it does not appear to be the case that the names of public figures, entertainers, celebrities, or characters in television shows or movies exert an outsized influence. However, negative associations (with scandal or a reviled or comic figures (Adolf Hitler or Donald Duck) do affect names’ popularity. Social movements, especially feminism, have had an impact on naming, with girls now more likely to receive cross-gender or androgynous names.

The relationship between ethnicity and social class and naming patterns is complex. Curiously, religious names came into fashion at precisely the time that church attendance was dropping and parents who were most active religiously were the least likely to give their children Old Testament names. Today, fewer practicing Catholics name their children after saints. Some ethnic groups, notably Irish Americans, tend to draw upon names with a clear ethnic identification (such as Megan, Kelly, Caitlin, Erin), while other groups, such as Italian Americans, do not. Currently, it is common among Mexican Americans to adopt girls’ names that end with an “–a” or names that have both traditional and Anglo counterparts (like Angela), while among boys’ certain names with clear ethnic connotations, like Jose or Jesus have declined, while others, like Carlos, have grown more common. Meanwhile, highly educated mothers are more likely to give daughters names that connote strength and substance (such as Elizabeth or Catherine).

History Through…

…Language

Each generation coins its own distinctive words. The 1920s brought “attaboy,” “bootleg,” and “skedaddle.” World War II brought us “swell” and “gung ho.” The 1960s popularized “cool,” “groovy,” and “psychedelic.” The 1970s and 1980s brought “slacker” and “grunge.”

As conditions of life shift, so does the vocabulary. Some new words are technology-driven, like “networking” or “selfie.” Some result from shifts in demography, like “blended family,” which arose as rates of divorce and remarriage became increasingly common.

In this activity, we will look at the backstory of everyday words and see what they tell us about American history.

Hoodlum

We know what a “hoodlum” is—a young ruffian. But where did the word come from? From San Francisco in the late nineteenth century. The word first appeared in English in 1871.

At that time, youth gangs in San Francisco repeatedly attacked Chinese immigrants, throwing bricks at them and beating them.

An 1875 article in Scribner’s Magazine described the gangs of young white men this way: “The Hoodlum is a distinctive San Francisco product. …He drinks, gambles, steals, runs after lewd women, and sets buildings on fire. One of his chief diversions, when he is in a more pleasant mood, is stoning Chinaman. That the Hoodlum appeared only three or four years ago is somewhat alarming.”

Anti-Chinese violence reached a peak in 1877, when anti-Chinese rioting left four immigrants dead and destroyed $100,000 worth of property. Five years later, the U.S. Congress enacted the first law restricting immigration, The Chinese Exclusion Act. Wrote the New York Times: “The plain truth is that a violent and discourteous act was demanded by the hoodlum sentiment of the Pacific coast, and this demand has been listened to.”

Hipster

What’s a hipster? An affluent young bohemian who lives in gentrifying neighborhoods and who is caught up in the latest fashion and culture trends. The word comes from hip, that is, cool and trendy.

Hipsters seemed to appear out of nowhere during the 1990s.

Where did the word come from? From jazz during the 1930s. Jazz generated its own lingo or jive. There were words like hip cat, daddy-o, baby, beat (exhausted), blow your top, boogie woogie, bread (money), bug (to annoy), chick (young woman), clinker (something fluffed), dig (understand), drag (boring), gig (a job), groovy, pad (apartment), and split (leave).

Racism

The first recorded use of the word racism was by a man named Richard Henry Pratt in 1902. Pratt wrote this: “Segregating any class or race of people apart from the rest of the people kills the progress of the segregated people or makes their growth very slow. Association of races and classes is necessary to destroy racism and classism.”

Today, Pratt is best known for a phrase: “Kill the Indian and save the man.”

Here’s exactly what Pratt said: “A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one,” Pratt said. “In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead.

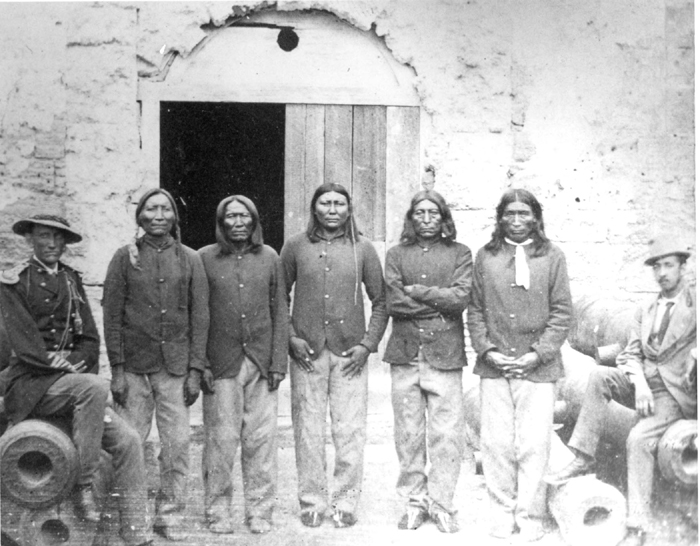

At the time, Pratt was considered a humanitarian who wanted to solve the nation’s “Indian problem.” He feared that Indians would die out and he thought the best way to save Indians was through assimilation and education. Congress gave him an abandoned military post in Carlisle, Pennysylvannia, to set up a boarding school for Native children. The government withheld rations from families which refused to send their children to the boarding school.

The Carlisle school sought to totally erase Indian culture. Students were forbidden from speaking Indian languages or from practicing Indian religions. He cut their hair and forced them to dress like whites.

At the school, beatings were commonplace and tuberculosis ran rampant.

So we might ask, was Pratt himself a racist?