Witchcraft in New England

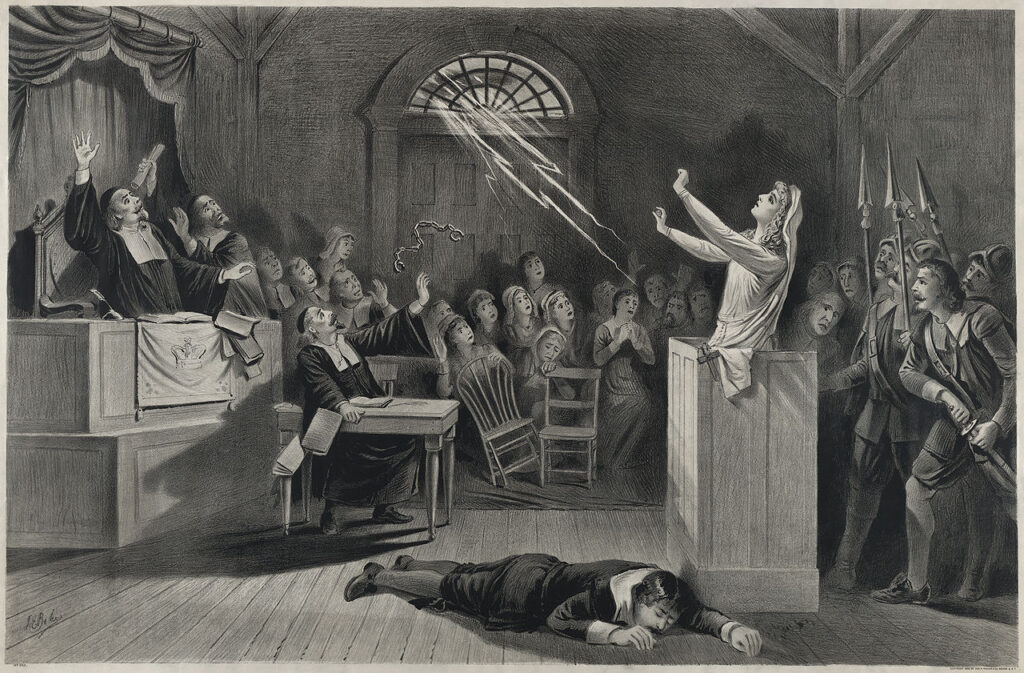

The Salem Witch Scare

In 1691, a group of girls in Salem, Massachusetts began acting strangely, behavior that was attributed to witchcraft. Under torture, an Indian slave named Tituba, said that a number of Salem’s residents were guilty of witchcraft. Tituba’s confession ignited a witchcraft scare which left 19 men and women hanged, one man pressed to death, and over 150 more people in prison awaiting trial.

For two decades, New England had been in the grip of severe social stresses. A 1675 conflict with the Indians known as King Philip’s War had resulted in more deaths relative to the size of the population than any other war in American history. A decade later, in 1685, King James II’s government revoked the Massachusetts charter. A new governor, Sir Edmund Andros, sought to unite New England, New York, and New Jersey into a single Dominion of New England. He also tried to abolish elected colonial assemblies, to restrict town meetings, and to impose direct control over militia appointments, and permitted the first public celebration of Christmas in Massachusetts. After William III replaced James II as King of England in 1689, Andros’s government was overthrown, but Massachusetts was required to eliminate religious qualifications for voting and to extend religious toleration to sects, such as the Quakers.

The late seventeenth century also marked a sudden increase in the number of slaves in New England. The 1637 Pequot War produced New England’s first known slaves. While many Indian men were transported into slavery in the West Indies, many Indian women and children were used as household slaves in New England. The 1641 Massachusetts Body of Liberties recognized perpetual and hereditary servitude (although in 1643, a Massachusetts court sent back to Africa some slaves who had been kidnapped by New England sailors and brought to America). Tituba was one of the growing number of slaves imported from the West Indies.

Probably an Arawak born in northeastern South America, Tituba had been enslaved in Barbados before being brought to Massachusetts in 1680. Her master, Samuel Parris, had been a credit agent for sugar planters in Barbados before becoming a minister in Salem, Massachusetts. In late 1691, two girls in Parris’s household and two girls from nearby households began to exhibit strange physical symptoms including convulsions and choking. To counteract these symptoms, Tituba made a “witchcake” out of rye meal and urine. This attempt at counter-magic led to Tituba’s arrest for witchcraft. She and two other women—Sarah Good and Sarah Osborne—were accused of bewitching the girls. Tituba confessed, but the other two women protested their innocence. Good was executed; Osborne died in prison.

Tituba’s confession that she had consorted with Satan and attended a witches’ coven fueled fears of a diabolical plot to infiltrate and destroy Salem’s godly community. In her testimony, Tituba drew upon Indian and African, as well as English, notions of the occult.

Tituba later recanted her confession, saying that she had given false testimony in order to save her life. She claimed “that her Master did beat her and other ways abused her, to make her confess and accuse…her Sister-Witches.”

The witchcraft scare soon spread across eastern Massachusetts. Of the approximately 150 people formally charged during the crisis, only twenty-four resided in Salem Village (now Danvers). More people had been accused of witchcraft in neighboring Andover than in Salem Town or Salem Village.

The witchcraft scare helped to discredit belief in witchcraft. The judges repented their sinfulness, and Massachusetts Bay Colony itself apologize for the grizzly episode just a few years after it took place and provided financial compensation to the families of the victims.

Witchcraft in New England

Most people in the early modern world believed in the existence of witches who gained supernatural power by signing a pact with Satan. The Salem witch trials were not a unique event. In continental Europe, where witch hunts were much more common than in America, thousands of people were executed, often isolated and impoverished older women who were regarded as a drain on community resources. As late as 1787, outside of Independence Hall where the framers were drafting the U.S. Constitution, a Philadelphia mob killed an accused witch.

In the half century before the Salem trials, more than 80 people were put on trial for witchcraft in Massachusetts and Connecticut alone. During the seventeenth century, some thirty-two people were executed for witchcraft in the American colonies.

What was unique about the Salem witch trials was the number of people who were accused and convicted. In previous witch trials, judges had imposed high standards of proof which resulted in a majority of the accused being acquitted. But when England revoked Massachusetts’s charter in 1685, it threw the judicial system into disarray. The special court set up in Salem allowed the use of “spectral evidence”: testimony from victims of a vision that they had of the person who was tormenting them. Further, the court permitted the use of psychological pressure and even torture to obtain confessions and ruled that anyone who confessed, identified fellow witches, and repented would go free.

The Salem witch scare had complex social roots. It drew upon pre-existing rivalries and disputes within the rapidly-growing Massachusetts port town: between urban and rural residents; between wealthier commercially oriented merchants and subsistence-oriented farmers; and between Congregationalists and other religious denominations: Anglicans, Baptists, and Quakers. The witch trials offer a window into the anxieties and social tensions that accompanied New England’s increasing integration into the Atlantic economy.

For the educated Puritan elite, there was double irony in the fact that the witch scare erupted in Salem. The word “salem” means peace, and the town’s founders had hoped that Salem would be a village of peace. Further, they had drawn the word salem from Jerusalem, hoping that this new village would serve as a foundation for a new Jerusalem.

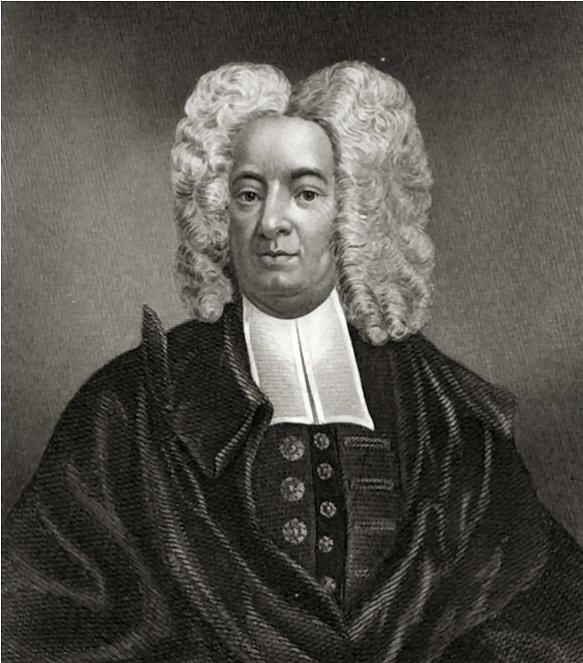

In this selection, written a year after the Salem episode, Cotton Mather (1663-1728), one of New England’s leading Puritan theologians, defends the trials, depicting New England as a battleground where the forces of God and the forces of Satan will clash. But guilt over this grizzly episode gradually ate into the New England conscience, and in 1697 Massachusetts held a public fast to mourn the blood that had been unjustly shed.

A descendant of one of the witchcraft judges, the novelist, Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864), dwelt in his writings on hidden guilt — sexual, moral, and psychological. In an early tale, he wrote: “In the depths of every heart, there is a tomb and dungeon, though the lights, the music, the revelry above us may lead us to forget their existence, and the…prisoners whom they hide.” One might speculate that his preoccupation with the complexities of human motivation and his lack of faith in progress and human perfectibility stemmed in part from his awareness of his ancestor’s involvement in the witchcraft affair.

Cotton Mather, The Wonders of the Invisible World, 1693

The New Englanders are a people of God settled in those, which were once the devil’s territories. And it may easily be supposed that the devil was exceedingly disturbed when he perceived such a people here accomplishing the promise of old made unto our Blessed Jesus—that He should have the utmost parts of the earth for His possession….

The devil is now making one attempt more upon us; an attempt more difficult, more surprising, more snarled with unintelligible circumstances than any that we have hitherto encountered; an attempt so critical, that if we get well through, we shall soon enjoy halcyon days, with all the vultures of hell trodden under our feet. He has wanted his incarnate legions to persecute us, as the people of God have in the other hemisphere been persecuted; he has, therefore, drawn his more spiritual ones to make an attack upon us. We have been advised by some credible Christians yet alive that a malefactor, accused of witchcraft as well as murder, and executed in this place more than forty years ago, did then give notice of a horrible plot against the country by witchcraft, and a foundation of witchcraft then laid, which if it were not seasonably discovered would probably blow up and pull down all the churches in the country.

And we have now with horror seen the discovery of such a witchcraft! An army of devils is horribly broke in upon the place which is the center, and after a sort, the firstborn of our English settlements. And the houses of the good people there are filled with the doleful shrieks of their children and servants, tormented by invisible hands, with tortures altogether preternatural. After the mischiefs there endeavored, and since in part conquered, the terrible plague of evil angels has made its progress into some other places, where other persons have been in like manner diabolically handled.

These our poor afflicted neighbors, quickly, after they become infected and infested with these demons, arrive to a capacity of discerning those which they conceive the shapes of their troublers; and notwithstanding the great and just suspicion that the demons might impose the shapes of innocent persons in their spectral exhibitions upon the sufferers (which may prove no small part of the witch plot in the issue), yet many of the persons thus represented, being examined, several of them have been convicted of a very damnable witchcraft. Yea, more than twenty-one have confessed that they have signed unto a book, which the devil showed them, and negated in his hellish design of bewitching and ruining our land….

Now, by these confessions it is agreed that the devil has made a dreadful knot of witches in the country, and by the help of witches has dreadfully increased that knot; that these witches have driven a trade of commissioning their confederate spirits to do all sorts of mischiefs to the neighbors; whereupon there have ensued such mischievous consequences upon the bodies and estates of the neighborhood as could not otherwise be accounted for; yea that at prodigious witch meetings the wretches have proceeded so far as to concert and consult the methods of rooting out the Christian religion from this country, and setting up instead of it perhaps a more gross diabolism than ever the world saw before. And yet it will be a thing little short of miracle if, in so spread a business as this, the devil should not get in some of his juggles to confound the discovery of the rest.